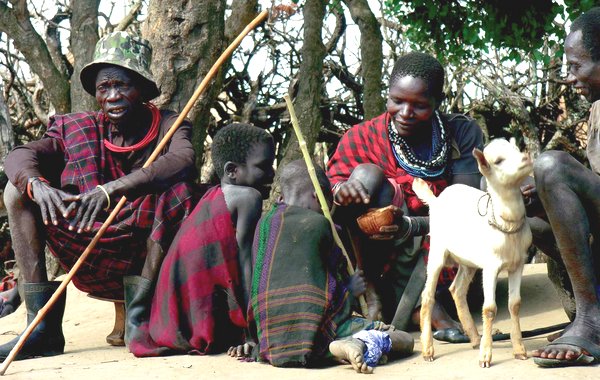

Ikland recounts a quest to re-connect with the Ik people, in a world dominated by cultural colonialism. For producer Cevin Soling, they represented the last outpost of imagination in a world devoid of myth. Soling and his crew risked their lives by traveling through war-ravaged northern Uganda to reach them. Their experience was alien and surreal in ways only Jonathan Swift might have imagined…

Louis Proyect on the documentary film Ikland

By Louis Proyect, published in The Unrepentant Marxist

When documentary filmmaker Cevin Soling was in seventh grade, his social studies teacher passed out a copy of an essay by Lewis Thomas titled “The Iks.” It referred to a small tribe in northern Uganda that might have been called “the Ickies” based on what Thomas wrote:

The message of the book [anthropologist Colin Turnbull’s “The Mountain People“] is that the Iks have transformed themselves into an irreversibly disagreeable collection of unattached, brutish creatures, totally selfish and loveless, in response to the dismantling of their traditional culture. Moreover, this is what the rest of us are like in our inner selves, and we will all turn into Iks when the structure of our society comes all unhinged.

They breed without love or even casual regard. They defecate on each other’s doorsteps. They watch their neighbors for signs of misfortune, and only then do they laugh. In the book they do a lot of laughing, having so much bad luck. Several times they even laughed at the anthropologist, who found this especially repellent (one senses, between the lines, that the scholar is not himself the world’s luckiest man). Worse, they took him into the family, snatched his food, defecated on his doorstep, and hooted dislike at him. They gave him two bad years.

Ikland is a 2011 documentary about a journey into northern Uganda and visit with the notorious Ik people. Produced by Cevin Soling, and directed by Soling and David Hilbert

Three decades later, Soling decided to travel to Ik territory and meet the people who were either maligned by Turnbull or lived up (or down) to the portrait. The chronicle of that voyage is in the marvelous documentary Ikland. As someone who has followed controversies in academic anthropology for the better part of two decades, I can say that this film should be required viewing in anthropology classes everywhere. It is a singular lesson in how the social scientist can impose their own worldview on an innocent people in a manner that reminds one of colonial domination. After all, Turnbull’s Britain once ruled all of Uganda so why shouldn’t he have his way with a mere tribe?

While it was within the realm of possibility that the Ik were as bad as Thomas portrayed them (he did blame their obnoxious traits on circumstances forced on them rather than any genetic predisposition), Soling must have sensed that another reality lurked beneath the surface as he said in a statement on the Ikland website:

I also had guiding principles of what not to do. I did not want to take an objective detached approach of treating people as experimental subjects, where comparisons to the viewer become implicit. At the same time, I did not want to take the other extreme of idealizing their society. When people were interviewed, I designed a conversational tone to overcome inherent distance, which focused on their daily concerns and enabled their dignity to emerge.

After watching Ikland, one cannot help but think that Soling’s trek into Ik territory was also a “voyage into the unknown, illuminated by only an almost superhuman belief” that the intended subjects of the film were so deserving of having their story told that any sacrifice made on their behalf would be worth it. In Soling’s case, and that of the tiny production staff that accompanied him, that sacrifice might have been their lives.

As documented in the film with surprising casualness and even a comic tone, the trip into northern Uganda involved numerous threats to health and safety. Soling and his comrades sleep in an infirmary in a tiny village, the nearest thing to a hostel in the Ugandan countryside en route to their destination. In nearby beds, there are people suffering from Dengue fever and anthrax. As they continue north, they pitch tents on a dirt road (more like a trail) and are awoken in the middle of the night by growling lions just outside the flaps. In a phone interview conducted with the director, he revealed that the only thought that came to him was this is where I am going to die. Continuing further, they run into a herd of elephants and once again escape with their lives. (African elephants—unlike their Indian brethren—are not only untrainable, they are violently hostile to people.) But the biggest threat of all was bandits and the feral combatants of The Lord’s Resistance Army, a group prone to wanton amputations and executions. While on the road in the middle of the night, the tiny convoy is attacked by small arms fire and only survives by driving ahead on punctured tires.

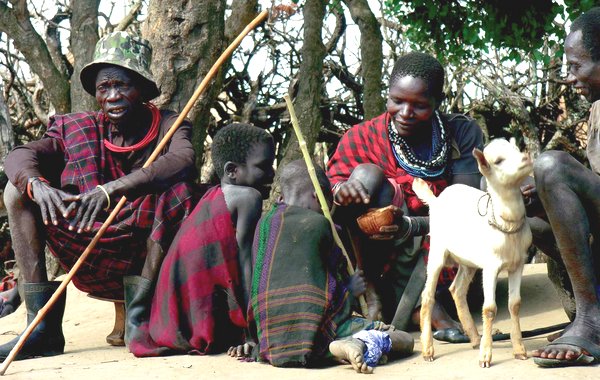

When they finally arrive in Ik territory, they are greeted warily. Few whites venture that far north and the Ik people tend to view all outsiders with some degree of suspicion since they have been preyed upon by hostile tribes in Uganda and the Turkana from Kenya to the north. The Turkana are warlike pastoralists who raid in order to steal food and cattle or goats reminding me in some ways of the Comanche who used to launch raids into Mexico in the 1850s. Despite having lost a number of their tribe to Turkana raiders in recent days, an Ik leader tells Soling that the Turkana can be generous when times are good. Given the desertification impacting almost all of northern Africa today and the exploitation of fertile land for agri-exports like coffee or cotton, it is understandable why the Turkana would be on the warpath much of the time.

Once the film crew settles into a daily routine with their hosts, we learn that Colin Turnbull’s analysis was not to be trusted. Like most people living communally, the Ik share their goods. When asked if some of the tribe hoards during a famine, they reply that in such times nobody has anything so there is nothing to hoard. Soling’s goal in enabling the Ik “dignity to emerge” is met with flying colors. As survivors of terrible privations, the Ik remain stoic and generous with each other and accepting and good-natured toward their guests. Perhaps the only defecation left on a doorstep was Colin Turnbull’s misbegotten book.

Watch this video on YouTube

One of Turnbull’s sharpest critics within the profession is Bernd Heine, whose “The Mountain People: Some Notes on the Ik of North-Eastern Uganda” (African: Journal of the International Institute, Vol. 55, No. 1, 1985) sets the record straight.

To start with, Turnbull visited the village of Pirre, an Ik center, but he came at a time when war forced non-Ik peoples to seek temporary refuge since it was the only village in the area that was policed and hence safe from banditry or terror. At times, therefore, the Ik were a minority there. Some of his main informants were not Ik at all but members of the Diding’a tribe.

Another of Turnbull’s errors was to view the Ik as hunter-gatherers like the pygmies he had also researched. He theorized that their anti-social behavior had something to do with being deprived of their livelihood since the state had banned hunting in Kidepo National Park, something that Lewis Thomas repeated:

The small tribe of Iks, formerly nomadic hunters and gatherers in the mountain valleys of northern Uganda, have become celebrities, literary symbols for the ultimate fate of disheartened, heartless mankind at large. Two disastrously conclusive things happened to them: the government decided to have a national park, so they were compelled by law to give up hunting in the valleys and become farmers on poor hillside soil, and then they were visited for two years by an anthropologist who detested them and wrote a book about them.

Thomas got the business about an anthropologist detesting them right, but they were never nomadic hunters. Instead they were farmers for at least 3,000 years according to Heine, and as such quite good at it. Turnbull never figured out that they were farmers and kept looking for evidence of hunters being deprived of their way of life, almost one supposes like members of the NRA having their worst nightmare come true.

Watch this video on YouTube

One of the most amusing and revealing passages in Heine’s critique deals with Turnbull’s flawed understanding of the Ik language:

Usually one of the first things an anthropologist in the field learns is the greetings. Turnbull made an effort, but with limited success. He notes, for example, that ‘the common, everyday greeting’ is ida piaji (Turnbull, 1974: 246). The Ik have a wide range of greeting forms, depending in particular on the time of the day. One of them is i-ida? (‘Are you [all right]?’), to which one replies, i-ida ‘bia ‘j? (‘Are you [all right] as well?’). It is probably the latter which he calls the ‘traditional’ or ‘common, everyday greeting’. It would seem that for all the two years he lived among the Ik he was not aware that he was greeting them with a reply to a greeting, furthermore with one which is used neither during the morning (ep-ida) nor during the afternoon hours (iria-ida).

I got a laugh out of this since my Turkish professor once read me the riot act when I told him “güle güle”, as a way of saying goodbye. Don’t you know, he said, the person staying behind says this, not the person leaving? Of course, I never claimed to be an expert on Turkish culture so I might be excused. Turnbull is another story altogether apparently.

To read the entire Louis Proyect review of Ikland, go to the Unrepentant Marxist.

Louis Proyect’s articles have appeared in Sozialismus (Germany), Science and Society, New Politics, Journal of the History of Economic Thought, Organization and Environment, Cultural Logic, Dark Night Field Notes, Revolutionary History (Great Britain), New Interventions (Great Britain), Canadian Dimension, Revolution Magazine (New Zealand), Swans and Green Left Weekly (Australia).

Updated 4 March 2023

Pingback: A Natural History of Love, by Diane Ackerman | Rituleen Reads

Gule gule means ‘go laughing’.