Sick, starving and dying sea lion pups are washing up on the shores of California in record numbers this year. The culprit? An unusual blob of record warm water parked off the North Pacific Coast for a year and a half, affecting circulation and weather patterns with no relief in sight. Hence, sardine fisheries have collapsed with wildlife heading north.

Sick, starving sea lion pups wash up in record numbers on California coast

By Peter Hecht, Published in The Sacramento Bee

SAUSALITO. Sick and starving, the 8-month-old sea lion pup dubbed “French Toast” braved an arduous journey to get here.

Separated from his mother in the Channel Islands in Southern California, he was found stranded on a beach near Carpinteria. Rescue workers moved him 350 miles to a marine hospital in the Marin Headlands above San Francisco. There, veterinarians put him under anesthesia. They injected antibiotics to save his left eye from an ulcer, administered painkillers for virus sores on his flippers and hydrated him with electrolytes.

Along the length of the California coastline, an extraordinary rescue effort is underway. In January and February alone, 1,450 malnourished or dying sea lion pups have washed up on shore – compared with just 68 in the same period last year.

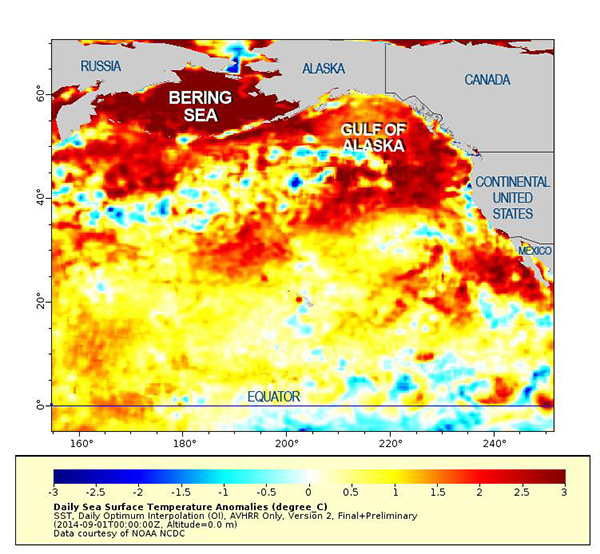

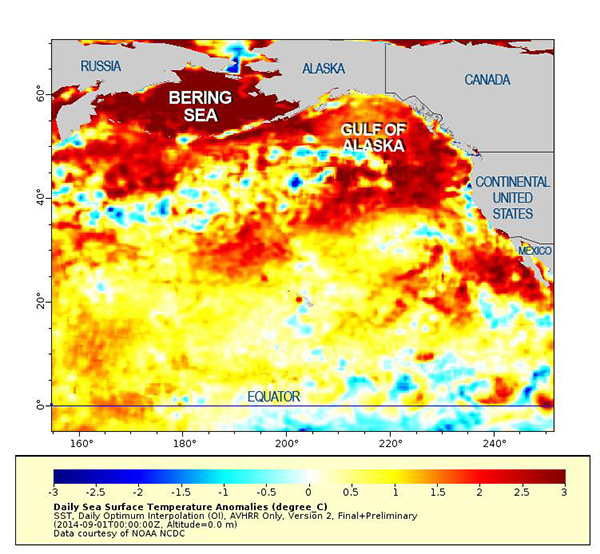

Marine biologists and climate scientists for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration say the culprit is a mass of warm coastal water that’s imperiling breeding and nursing colonies of California sea lions. The so-called “unusual mortality event” – following a much smaller bubble of sea lion strandings and deaths in 2013 – has triggered questions about the overall health and volatility of the California ocean environment.

Scientists say the warmer waters can prevent sea lion mothers from finding sufficient quantities of anchovies, mackerel, sardines and other fish to provide nutrition for nursing. So they are leaving behind their pups, mostly born each June on four islands in Southern California, to forage for food for extended periods – far beyond their normal two or three days at sea.

Experts say it’s the warm water. Scientists believe warmer coastal waters force the prey of sea lions — squid and sardines, for example — deeper beneath the ocean’s surface. Then nursing sea lion mothers must look further afield for food, leaving their pups for longer than normal. Deprived of sustenance and weakened, the pups limply wash ashore. — Nick Kirkpatrick, Washington Post

As a result, tens of thousands of pups birthed last summer are believed to be dying on the islands as others, fearing their mothers have abandoned them, set out into the ocean and drift or wash ashore sometimes hundreds of miles away.

“These are pups that should be nursing on their mothers,” said Dr. Shawn Johnson, director of the veterinary science department at The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito. “They’re (arriving) extremely emaciated. They have no energy stores. They’re just skin and bones, wasting away and on the brink of death.”

From Sea World in San Diego to the Northcoast Marine Mammal Center in Del Norte County, seven California marine rescue facilities are tube-feeding fish gruel to skeletal pups, helping them learn to catch and digest whole fish and administering vitamins and medication to ward off pneumonia and skin infections.

“It’s a very intense operation going on right now,” said Sea World spokesman David Koontz.

Trained teams dispatched by The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito have rescued 340 sea lion pups since Jan. 1 on hundreds of miles of California coast. About 150 of the animals have since died. Twenty veterinary professionals and dozens of volunteers are working doggedly to save the other pups and nourish them back to health. Fifteen were recently released back into the wild.

Sea World rescue vehicles also are pulling 20 sea lions a day off beaches in San Diego County. With a combination of volunteers and veterinary staff from as far away as parks in San Antonio, and Orlando and Tampa, Fla., Sea World has tended to 350 rescued sea lion pups since Jan. 1.

Volunteers for the California Wildlife Center in Los Angeles County are rescuing sea lion pups that have washed into marinas, some desperately trying to climb onto small boats or kayaks. San Pedro’s Marine Mammal Care Center at Fort MacArthur has taken in over 270 malnourished pups from the nearby coast. “It’s all hands on deck,” said marketing manager Raymond Simanavicius.

An unusual threat is looming off the Pacific coast of North America from Juneau in Alaska to Baja California. Now roughly 2000 kilometers wide and 100 meters deep, a mass of warm water that scientists are calling “the blob” has lingered off the coast for a year and a half and has set temperature records, with waters between 1 °C and 4 °C warmer than normal. The blob has changed water-circulation patterns, affected inland weather and reshuffled ecosystems at sea. — The New Scientist

httpvh://youtu.be/UIf5T7UP_zk

California Sea Lions Pups in Crisis, Video By Manny Crisosomo

STORY: Ocean Acidification Threatens Alaskan Crab Fishery

‘Never stop rescuing animals’

At the hilltop Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, overlooking the Pacific Ocean, volunteers try to return feeble pups to vitality.

There, Sherry Riley connected a giant syringe – full of a milky solution of ground herring – to a feeding tube. She tried to ease a rubber feeding tube down the throat of a resistant pup named Perkins. But the female, wrapped in a towel and gently held down by another volunteer, wasn’t taking it.

Perkins grit her teeth. Volunteers pried her mouth open and slid the tube down. Perkins began to chew, ingesting the solution.

Riley’s regular job involves treating humans as an emergency room nurse in Santa Rosa. But she turned out at 5 a.m. on her day off to help minister to sea animals in distress. She fed scores of animals until nearly dusk. “Sometimes, it’s really overwhelming,” Riley said.

The nonprofit marine rehabilitation center and hospital is feeding 1,300 pounds of fish a day to rescued sea lion pups. The animals are housed in numerous caged enclosures with small ponds. They’re given names that are listed on charts, and their foreheads are dabbed with identifying combinations of grease paint.

Federal regulators in April approved an early closure of commercial sardine fishing off Oregon, Washington and California to prevent overfishing. The decision was aimed at saving the West Coast sardine fishery from the kind of collapse that led to the demise of Cannery Row, made famous by John Steinbeck’s novel of the same name set in Monterey, California. — NBC News

Veterinarians write feeding and medication instructions for each. In a fenced pen for pups healthy enough to dive and swallow fish, volunteers Michelle Corsi, Sue Mancusi and Debbie Wertheimer tossed fingerlings packed with individualized vitamins and meds to colored-coded animals named Kangaroo, Ice Cube, Magpie and Goldy.

Corsi is an environmental scientist from Vancouver who has volunteered at the Sausalito facility since moving to San Francisco several years ago. Mancusi is a retired nurse from Santa Rosa. Wertheimer is a dental hygienist from San Rafael. Together, they are responding to a California marine emergency. Corsi said she felt inspired by a quote she had read on the Internet: “Never stop rescuing animals. You might lose your mind. But you’ll find your soul.”

Away from the pens filled with this year’s sick sea lion pups, scientists are working to find answers about current and, potentially, long-term phenomena affecting the health and well-being of the species.

Nate Mantua, a NOAA ecologist and climatologist based in Santa Cruz, said unusually weak winds from the north have prevented colder water from flowing south into breeding and nursing areas. The problem is worsened by stronger warm winds from Mexico.

Mantua said the warming condition is akin to what occurs during a tropical El Niño storm system – without the storm – and “is as strong as anything that is in the historical record.” Water temperatures are 2 to 5 degrees above normal; the warm plumes extend 100 feet deep from Baja California to Alaska.

The elevated temperatures are expected to persist in coming months unless there is a strong shift in the wind, Mantua said. “I don’t think there is any indication that will happen,” he said.

“It has always seemed strange to me…The things we admire in men, kindness and generosity, openness, honesty, understanding and feeling, are the concomitants of failure in our system. And those traits we detest, sharpness, greed, acquisitiveness, meanness, egotism and self-interest, are the traits of success. And while men admire the quality of the first they love the produce of the second.” — John Steinbeck, Cannery Row

STORY: Disappearing Cod: Sustainable Populations Require Long-Term Action

A changing environment

California’s sea lion population, decimated in the late 1800s and early 1900s by hunters harvesting blubber for fuel and fur for coats and hats, now totals 300,000. That’s a sixfold increase since Congress promoted rescue and preservation efforts and effectively banned poaching under the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Since 2004, the number of sea lion pups washing up on California coasts has mostly fluctuated between 100 and 150 a year. Scientists noted a worrisome anomaly in 2013, when 1,171 famished pups were stranded on shore – including 309 in January and February. Then, scientists blamed the phenomenon on unseasonably cold waters.

“From a sea lion and biology perspective, we’re learning that the environment is changing every year and the animals are having to adjust,” said Sharon Melin, a Seattle-based NOAA wildlife biologist. “When they can’t, we’re seeing high mortalities.”

The bulk of California sea lion pups are conceived and birthed on four islands, San Miguel, San Nicolas, San Clemente and Santa Barbara, part of the Channel Islands in Los Angeles, Ventura and Santa Barbara counties.

Melin, who has been studying sea lion populations on San Miguel and San Nicolas, said scientists are recording devastating effects from the current warm-water event. In September, the average weight of 3-month-old pups on the two islands was 19 percent less than normal. In February, the average weight of 7-month-old pups was 44 percent less than normal. The pups gained little or no additional weight from October through January.

“Where are those sea lions going to go? Right now, there just isn’t enough food out there,” says Josiah Clark, a consulting ecologist in San Francisco who has studied birds and marine life for more than 20 years. Clark says starving predators like the sea lions are a clear symptom of serious problems lower down on the food chain. In this case, climate change may be disrupting essential weather patterns—and bottle-feeding baby sea lions, he says, is not helping. — Alastair Bland, Smithsonian

On San Miguel, where 20,000 sea lions are born each June, Melin said researchers believe “probably close to 10,000 are dead, and we expect more to die over coming months.” She said the mortality rate is similar on San Nicolas.

Scientists say only the pups are in peril because sea lion adults and adolescents can swim long distances to feast on fish in more chilly waters to the north.

Melin and others say current ocean conditions could result in fewer sea lion births next June – and a decline in the overall population if other unusual events occur in coming years. Meanwhile, biologists and veterinarians say other ocean factors, including depleted fish populations, may present an ongoing challenge for the animals.

“There is a complex process happening in our ocean,” said Johnson of The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito. “The ocean is clearly under stress from the warmer water and, potentially, overfishing. These sea lions are telling us we should be very concerned about the health of our oceans.”

“It’s not a question of either doing rescue work or mitigating the effects of climate change. It is precisely the Center’s work in researching how a top predator is starting to fail that puts a magnifying glass to the larger issues of climate change, pollution and overfishing that are destroying our oceans,” Clare Simeone, a conservation medicine veterinarian with the Marine Mammal Center says in an emailed statement. “This work aids in understanding the effects of unprecedented changes in the environment and hopefully in mitigating and reversing them through increased scientific knowledge and shifts in environmental policy.” — Smithsonian

As sea lion pups wash ashore, the public is told not to approach or touch the animals because they may be carrying diseases or parasites, and could bite or lash out in fear. Instead, people are instructed to call hotline numbers for the state’s marine mammal rehabilitation centers and other trained wildlife rescue groups.

Even at The Marine Mammal Center, where most surviving pups will undergo six weeks of rehabilitation before they are capable of returning to the ocean, volunteers are told not to make eye contact, hand-feed them fish or do anything to alter their normal behavior.

“It’s hard because they’re like the golden retrievers of the ocean,” said center spokeswoman Laura Sherr. “Our crews get very attached to them. But we want to bring them back from a state of sickness so they can go back out into the wild.”

When the sea lion pup French Toast came out of the surgical room, shivering from the effects of the anesthesia, veterinary staff put him on a heated mat in a cage and turned away.

Veterinarian Dr. Cara Field noted that the pup, since arriving at the center in February, had gone from “barely tolerating calories” to having “put on a little weight and his coat looks better.” She said it was too early to know whether they had saved his infected eye. He can function in the wild with just one.

As French Toast raised his head, breathing in the coastal air with his young life on the mend, the satisfied staff pretended not to notice.