David Osborn from Rising Tide asserts all new fossil fuel extraction must immediately stop if we want any chance of a habitable climate and a livable future. The climate movement needs more actions like Swamp Line 9 in Ontario, which shut down a pumping station to protest the Enbridge Line 9 Tar Sands Pipeline Reversal.

Direct Action on Line 9: Moving Beyond the Keystone XL

By David Osborn, Published in CounterPunch

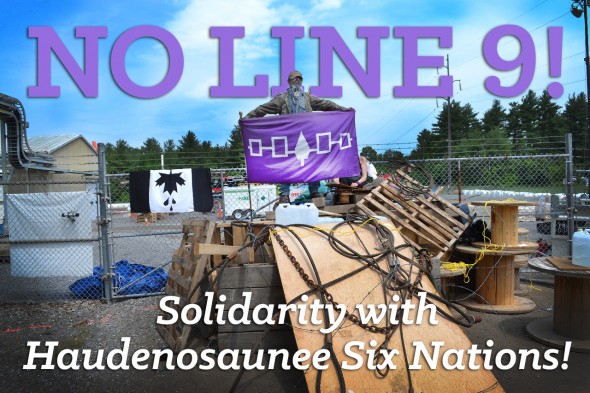

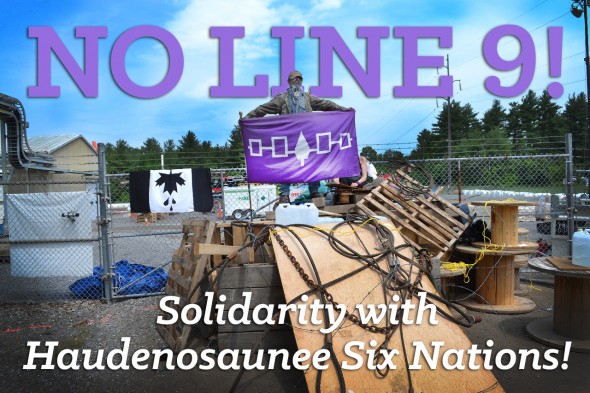

On the morning of June 20th a group of people walked onto the Canadian energy corporation Enbridge’s North Westover pumping station and occupied the facility. They called this blockade “Swamp Line 9.” The facility is part of what is called Line 9, a pipeline that moves oil west towards Sarnia and the refining facilities there. However, the industry has been engaged in an effort to slowly gain regulatory approval to reverse the pipeline, allowing it to carry tar sands oil east for refining or to the Atlantic coast for export. The pumping station for Line 9 had been shut down for work and remained shut down during the occupation as Enbridge employees were unable to access the site. The direct action effectively stopped all activity at the pumping station until June 26th when the Canadian authorities raided the occupation and arrested twenty people (you can support their legal fund here).

Watch this video on YouTube

Line 9 – The Tar Sands Come to Ontario, Video by Rachel Deutsch

This action came after over a year of growing grassroots opposition to Line 9 and represents another escalation in the climate movement to address the failure of existing political institutions to deal with the climate crisis. It also has had the effect of continuing to raise the profile of the various efforts to move tar sands oil out of Alberta and engage people in Ontario about the issue. Here, outside of Hamilton in Ontario, much like in East Texas, Maine, Washington State, Oklahoma, British Columbia, and elsewhere communities are taking direct action to confront the root causes of the climate crisis.

In confronting the expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure we also resist the devastating ecological transformation that occurs in service to markets and profit. In this sense this action, like those taking place across North America and the world, also represent people resisting the transformation of their communities by capitalism, which fundamentally drives the climate crisis with its need for exponential growth, its utilitarian view of the natural world as human-centered “resources” and its value of profit above all else.

Line 9 and Tar Sands

Encapsulated within the story of Line 9 is a glimpse of the changing energy politics of North America. The pipeline was originally built in 1975 to transport crude oil from Western Canada to Montreal refineries. Around the turn of the millennium the direction of the pipeline changed to bring imported oil into the refinery infrastructure in Ontario. With oil production booming in both the United States and Canada, and particularly with the landlocked tar sands megaproject needing to bring its product to market, the industry has slowly been trying to get regulatory approval for reversing the flow in order to bring oil westward again.

In the United States oil imports are down significantly, after peaking in 2008, as domestic production booms and there are numerous efforts to begin exploring export of not only oil, but coal and natural gas. The reversal process around Line 9 follows a prior proposal, called the Trailbreaker project, by Enbridge during 2008-2010 to reverse the pipeline to export on the Atlantic coast. The fragmenting of the current reversal efforts has allowed for easier regulatory approval and is almost certainly the result of a strategic decision by industry.

Portland, Maine enters the story courtesy of Hitler’s U-boats and their relentless campaign against Allied infrastructure during the Second World War. Tankers bringing crude to Montreal were suffering losses in the exposed entry into the St. Lawrence river. Aiming to provide for a less exposed route for tankers a 236-mile pipeline from Portland to Montreal was completed in 1941 allowing fuel for the war machine to flow with a lesser chance of encountering a torpedo. The pipeline was expanded from an 18-inch to 24-inch diameter in 1965 and some seventy tankers make a port call at the import facility each year.

The only problem is that Canadian and US demand for imported oil is only shrinking and fossil fuel corporations have made huge investments in the landlocked tar sands megaproject in Alberta. Their profits are constrained by their inability to move their product to market, especially with the recent rejection of the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipeline by the Province of British Columbia. The $6 billion dollar project would have the capacity to ship 525,000 barrels/day of tar sands oil to an export terminal on the coast of British Columbia. It also would cross numerous unceded First Nations’ territories and has mobilized enormous opposition. With BC having rejected the Enbridge proposal, the tar sands industry is facing larger setbacks to exporting tar sands through a region they once thought was a possibility. However, it should be emphasized that though having received a significant setback the project remains very much on the table with the final authority resting with the federal government.

To describe the development of the tar sands is almost beyond words and illustrates the extent to which capital is scraping the bottom of the barrel in its suicidal attempt to perpetuate growth and profit above life itself. With the first industrial attempts to exploit the tar sands in Alberta in 1967, efforts have ramped up as increasing oil prices (also reflecting the growing lack of easily accessible oil) have made the intensive process increasingly profitable. The process to get at tar sands, which are also slated to be exploited in Utah, is an extreme version of the similar extraction processes like fracking that are incredibly damaging in the increasingly desperate attempts to get at any fossil fuels remaining. To get at the tar sands, which are then processed into oil, the boreal forests of Canada are clear cut. These forests are some of the last intact and contiguous ecosystems in the world.

Two tons of the oil-containing bitumen, which produces only one barrel of oil, is gathered by massive machinery, washed with three barrels of water (which then become toxic polluted tailings), heated by natural gas (and soon proposed nuclear power plants) and out comes some of the dirtiest and most energy intensive energy ever produced. The result is an intensely polluted environment that has become toxic for the First Nation’s people that live there and devastated their communities. This comes on top of previous and ongoing displacement, the destruction of culture and other impacts that make this a clear continuation of the intergenerational trauma produced by colonialism.

The extent of the devastation underscores the extent to which capitalism is wreaking havoc on communities of life in all their forms. Humans, fish, trees and elk alike are inconsequential when the land that sustains them is seen only in terms of a human-centered resource and profit to be exploited. Huge swaths of Alberta have already been impacted as production from the tar sands has exploded to some 1.5 million barrels per day. And all of this oil needs to go somewhere. With a proposed expansion to 300,000 barrels/day and the full reversal of Line 9, this oil could be flowing to Portland, Maine filling tankers and corporate coffers. Unless we stop them.

The actions at the North Westover pumping station were taken in this context and to prevent the movement and export of tar sands oil. They also occurred as part of the continued growth of grassroots opposition to the Line 9 reversal. In May of 2012 there was a disruption organized at a meeting of the National Energy Board, which was reviewing the first proposed reversal by Enbridge. This was one of the earliest signs of community-based, grassroots opposition that went beyond the moderate engagement by NGOs that had occurred up until that point. Earlier this year, organizers in Hamilton blockaded Highway 6 where Line 9 crosses it and shut down the freeway for 90 minutes in recognition of the average number of reportable spills that Enbridge has each year in North America.

Enbridge, anticipating the escalating opposition donated over $44,000 to the Hamilton police, which created the occasion for further actions to mark the increasingly blurred line between the state and corporations. And recently an Ontario conference in Sarnia at the west end of Line 9 about tar sands expansion was disrupted with a young Aamjiwnaang First Nations woman inside unveiling a banner that read “you are killing my generation” while people outside banged on windows and used a siren that was similar to the emergency sirens used in Sarnia to note chemical spills or gaseous escapes.

The seven day occupation provided an important escalation of action against Line 9. It also provides for important reflections about organizing within a climate justice framework, which organizers of the action have been engaging. In a June 30th post following the end of the occupation the organizers made a post titled “Replicating Colonialism in the Struggle Against Line 9”. In it they reflected on criticism about the lack of communication and consultation with the Six Nations of the Grand River despite the relationships they had with members of that community. This particular case provides important insights applicable outside of this specific example regarding relationships often pursued by settler organizations with the indigenous people on whose land they organize or who are impacted by a given project.

With the Westover occupation we can see the difficulties inherent in transitioning from a place of simply having relationships to a form of relationship in which we are deeply and consistently engaged in organizing work and within which we take leadership from the community with whom the relationship has been formed. There is important and complex work needed in developing how groups can work in solidarity with impacted communities, take leadership from those communities and at the same time develop their own campaigns which foster new leadership within their group.

In all of this it is important for us to engage the climate crisis from understandings about social justice, the uneven impacts of the crisis and the systems of oppression and domination that so define our societies. We must deeply engage what it looks like to work appropriately with impacted communities and negotiate this depending on our own social locations. Thinking about how we are impacted by the climate crisis and how we might align that position with other communities for collective liberation is an essential and important approach.

Additionally, it is critical for us to be reflective about our actions, to acknowledge our mistakes and to start from a place of constructive engagement so that we can move forward and continue to ground our organizing in an anti-oppression framework. In their post-action reflections the organizers of the occupation at the North Westover pumping station have done important work in this direction. With this approach our organizing around the climate crisis not only opposes destructive practices but also begins to constitute new, liberatory forms of social relations that can be the basis for even greater social transformations beyond the climate.

Don’t Put All Your Eggs in One Basket

The climate movement in the United States has focused much of its resources – driven largely by mainstream environmental groups – on the Keystone XL pipeline. They have staked this out as the fight to have and have claimed its construction would be “game over for the climate.” Stopping the Keystone XL pipeline is clearly important as will be discussed later, but this strategy has been highly problematic. At full capacity the Keystone XL pipeline would move 830,000 barrels/day of tar sands oil to refineries and export facilities on the Gulf Coast of Texas. The existing Keystone pipeline system already moves 590,000 barrels/day. But Keystone XL isn’t the only way tar sands oil are proposed to be moved, nor is oil or even tar sands oil the only driver of climate change.

In addition to Line 9 and other tar sands pipelines there is a massive attempt to move the rapidly growing energy production of Canada and the United States abroad. With the advent of fracking technology and the marketability of tar sands these two nations are in the midst of an energy boom. The corporations that profit from these catastrophic developments want to move towards energy-exporting, petro-states, particularly as regulation, expansion to renewables and energy saving initiatives begin to limit domestic consumption.

In the northwestern part of the continent there is an extraordinary push to move not only tar sands oil but also coal, fracked oil and gas. With more than 15 coal, oil and gas export terminals proposed in the region it is emerging as a frontline in the push to move these fossil fuels abroad. Canadian environmental groups have had their own narrow focus on tar sands and similar to Keystone have largely targeted the Northern Gateway pipeline. However, the coal and gas export proposals in British Columbia have huge climate consequences. And despite the rejection of the pipeline, and perhaps because of it, the is a huge push to move oil by rail including a massive 380,000 oil terminal in Vancouver, WA.

Though ostensibly for Bakken shale oil, it has been made clear by the Port Commissioners reviewing the proposal that it should be prepared for tar sands oil spills and mitigation. The combined impact of these NW export projects alone would be three times that of Keystone XL. The expansion of the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline, which has less attention than the Northern Gateway pipeline did in regional Canadian climate politics, would move 890,000 barrels/day of tar sands to export facilities in British Columbia and oil refineries in Washington State. The Pacific Trails Pipeline has also had much less attention than Northern Gateway even though it would blaze a trail through the same region and along the same route. This pipeline would transport fracked gas and would pave the way for a renewed proposal of the recently rejected Northern Gateway Pipeline given its approval by the state and the fact that it follows the same right of way. If built Enbridge could argue that the clearcutting and service roads are already in place make for “less” impacts during construction. However, this pipeline is not going unchallenged and the Unis’tot’en have been resisting the pipeline including ejecting industry surveyors from their land and building a camp directly in the path of the pipeline.

No one pipeline is “game over for the climate” and focusing too narrowly prevents movement building across fossil fuel-type and region. In all of our work we need to broadly engage fossil fuels and the climate not only the specifics of a given project that we are opposing, whether it be fracking wells in Western Pennsylvania, a coal export terminal on the Columbia River, mountaintop removal in Appalachia or the Westover Pumping Station in Ontario. This way we can be sure to expand engagement beyond the NIMBY-orientation that political activation can often, or at least initially take, and move to broad-based systemic involvement to address the climate crisis and its roots in capitalism.

It is essential that individuals that enter a given struggle over a pipeline, fracking well or terminal over time come to see this not as a local land or pollution issue, but rather as a global climate issue. Then whatever the outcome of their local campaign they will remain engaged as part of a climate movement, rather than celebrating and going home. This is all the more important as we may lose big fights, including a potential loss with Keystone XL, and if we have mobilized people on the basis that this is the fight, we risk disengagement and burnout.

The Game is Rigged

The occupation of the Westover Pumping Station is reflective of a continuing shift in strategies and understandings of social change by the climate movement. It is also reflective of the increasing realization, particularly of late by more liberal participants in the climate movement, that the game is rigged. Politicians are bought off, they are owned by the fossil fuel corporations that we organize against and the existing political institutions are not up to addressing the climate crisis. In the United States oil and gas corporations dumped $150 million dollars into the coffers of candidates of both parties. This can be scary, particularly to the extent that we view these institutions and public policy as the only place in which social change can happen.

Luckily for us, the climate and the global communities already impacted by these monumental shifts this is not how social change happens. Social change happens when individuals acting together with others realize they can shape the world in which they live, that they have agency and power. Social change happens when we develop a critical consciousness about social relations and their fundamentally mutable and historically-specific nature. Direct action catalyzes this dual consciousness and is a vehicle for transformative social change.

Over the last years we have seen a huge shift towards communities taking control and taking action against the fossil fuel infrastructure that imperils their communities and the climate. This follows the strategy of historic social movements that did not focus their energy on Washington DC and instead understood that power resided and was built elsewhere. Recently the Idle No More movement has provided numerous examples of incredible action including the Aamjiwnaang blockade a of CN Railway line transporting toxic chemical into their community over twelve days in December and January. The blockade kept 420 cars per day out of the valley, which includes a series of petro-chemical facilities (i.e. chemical plants, oil refineries, rubber plants, etc.). In the fall of 2012 the Tar Sands Blockade, supported in part by Rising Tide North Texas, began in response to the construction of the southern leg of the Keystone XL pipeline.

With dozens of actions the blockade catalyzed thousands across the country and expanded to the north with Great Plains Tar Sand Resistance which recently shut down the construction of a pumping station near Seminole, Oklahoma. In British Columbia First Nations communities were instrumental in the setback of the Northern Gateway Pipeline and Wet’suwet’en peoples continue to take action against fossil fuel expansion with the Unist’ot’en camp, which is digging in along the proposed Pacific Trails natural gas pipeline. Also in the Northwest there have been two train blockades targeting existing and proposed coal export terminals and recently a large action and banner drop on the Columbia River that signified the region’s preparedness to engage in further direct action if any of the proposals move forward. And in Appalachia, communities continue to resist mountaintop removal such as by blockading the road leading to Alpha Natural Resources, which is deeply involved in the highly destructive practice.

This is the grassroots swell of community power that has moved even the big NGOs such as the Sierra Club to take symbolic arrestable action, breaking from a 120-year ban on civil disobedience. And these are but a few examples of the many direct actions that have occurred over the last year. It is only with the inclusion of this kind of action as part of a diversity of tactics that we can address the climate crisis. Targeting politicians in this context is a losing strategy for the type of transformational change needed and fundamentally misunderstands how social change happens and where power can be built, particularly in our corrupted political institutions.

In a similar vein one might ask if it was legal strategies by large NGOs and the Supreme Court that overturned the Defense of Marriage Act recently in the United States and legalized gay marriage in many places. On the contrary all the court did was recognize and institutionalize the social change that had already happened among millions of individuals in communities across the United States through diverse organizing work, including direct action, over the course of decades. Through community-based organizing and direct action we are able to find where power truly resides, in our communities, and actualize that power to build a broad-based climate justice movement. It is only once this has occurred that existing political institutions will move to address the climate crisis. And should they be unwilling or unable to do so at that point we will have begun to build the type of movements capable of replacing them.

If They Can’t Ship It, They Can’t Sell It

The boom of fossil fuel extraction in North America spells disaster for the climate and our communities. The petro-state, exporting dreams of fossil fuel CEOs must be stopped. The recent focus on transportation infrastructure and the circulatory flows of fossil fuels provide an excellent place for intervention and action. The nature and location of fossil fuel extraction means it must be moved to places of consumption and increasing export to markets abroad. And if they can’t move it, they can’t sell it. And if they can’t sell it, then it has to stay in ground.

This is the only moral place for fossil fuels to be in the moment in which we live. All new fossil fuel extraction must immediately stop if we want any chance of a habitable climate and a livable future. From that point we’ll need a just transition that includes an immediate and rapid reduction of existing fossil fuel use and extraction. In this movement actions such as those that occurred at the Westover Pumping Station are critical. It will be communities, taking direct action together, that will create the groundswell needed for advancing a just and sustainable future.

David Osborn is climate organizer working with Portland Rising Tide and Rising Tide North America. He is also a faculty member at Portland State University. He can be reached at david@portlandrisingtide.org.

Line 9 and Westover Pumping Station Occupation

Swamp Line 9 – http://swampline9.tumblr.com/

Hamilton Line 9 – http://hamiltonline9.wordpress.com/

Peak – Line 9 – http://www.anarchistnews.org/content/peak-resisting-line-9-april-2013

Against the Reversal – http://zinelibrary.info/files/against-the-reversal.pdf

Stopping Line 9 – http://rabble.ca/news/2012/09/enbridge-line-9-other-other-pipeline

Video about Line 9 – http://vimeo.com/56842880

Tar Sands and Associated Pipelines

Tar Sands Action SoCal – https://www.facebook.com/TarSandsActionSoCal

Yinka Dene Alliance Against BC Tar Sands Pipelines – http://yinkadene.ca/

Tar Sands Free NE – http://www.tarsandsfreene.org/about

Blocking the Arteries of the Tar Sands – http://www.alternativesjournal.ca/community/blogs/current-events/blocking-arteries-tar-sands

Tar Sands Emissions and US-Canadian Militarization – http://www.dominionpaper.ca/articles/3875

Northwest Export Terminals

Rising Tide Vancouver, Coast Salish Territories – http://risingtide.resist.ca/

Portland Rising Tide – http://portlandrisingtide.org/

Sightline Report: NW Fossil Fuel Exports – http://www.sightline.org/research/northwest-fossil-fuel-exports/

Mountaintop Removal

Radical Action for Mountain People’s Survival – http://rampscampaign.org/

Coal River Mountain Watch – http://crmw.net/

Mountain Justice – http://www.mountainjusticesummer.org/

Appalachian Voices – http://appvoices.org/

Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition – http://www.ohvec.org/

Keeper of the Mountains – http://www.mountainkeeper.org/

Fracking

Shadbush Environmental Justice Collective – http://shadbushcollective.org/

Stop the Frack Attack – http://www.stopthefrackattack.org/

Sightline Report: The NW Pipeline by Rail – http://www.sightline.org/research/the-northwests-pipeline-on-rails/

Marcellus Shale Earth First! – http://marcellusearthfirst.org/

Pingback: Idle No More LA: Poetry and Prayer at Petroleum Conference | WilderUtopia.com