Pristine beauty, danger, and wild risk make whitewater river rafting on the Middle Fork of the American River a must-face-seeming-death for paddlers. Despite a healthy Sierra Nevada snowpack, this free-flowing river stretch brings up questions of water sustainability and the zombie Auburn Dam proposal, among others. Why is dam removal an important movement? And what about the folly of plans to build 3,700 new not-so-clean hydroelectric dams across the world?

Desolation and Invigoration on the Middle Fork of the American

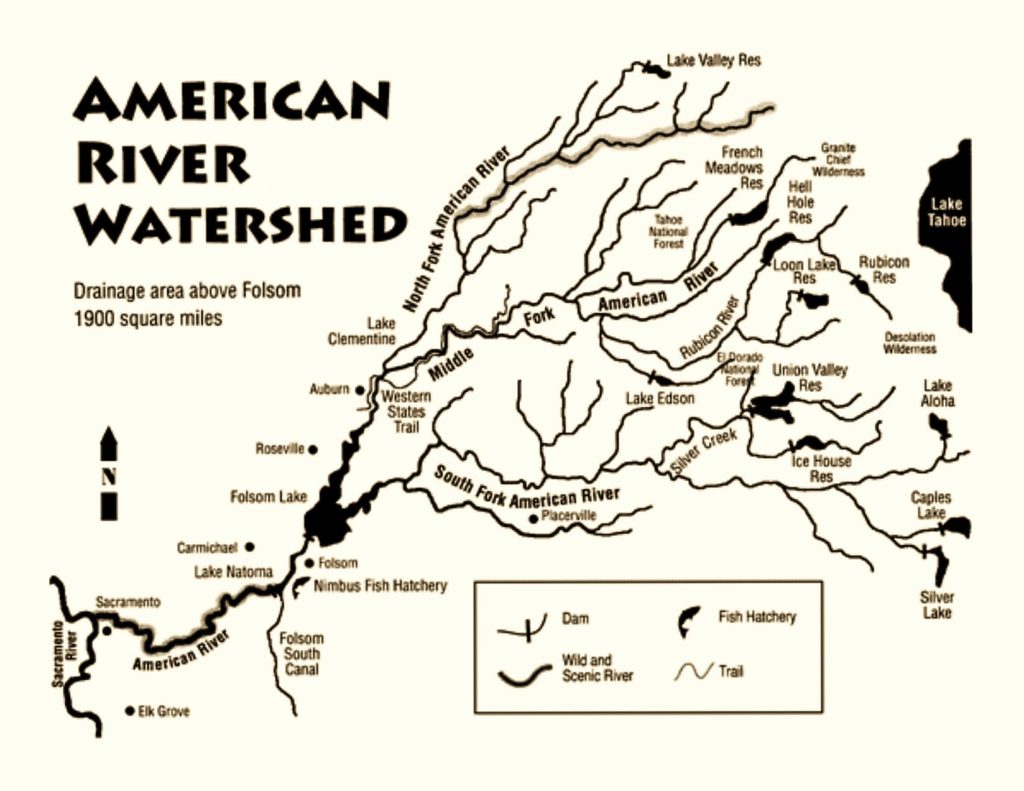

The Middle Fork of the American River that churns aquamarine and splashes through the Sierra Nevada foothills conjures multiple images: fishing for wild trout, rafting the whitewater rapids, and its foundational role in the historic gold mining of the Mother Lode and formation of the State of California. To the casual visitor the American seems wild, draining 1,900 square miles of Tahoe and El Dorado National Forests, including Granite Chief and Desolation Wildernesses, and flows life into the quaint Gold Rush towns like Placerville, Coloma, and Auburn. Yet, rivers like the American today face threats from the push for water sources in a oft-drought-parched state, hydroelectric dams for the power-hungry, as well as timber cultivation and real estate development.

As we crossed the Auburn-Foresthill Bridge, among the highest in the world built in 1971 to span a not-yet (or ever) constructed reservoir, I considered the question of damming rivers on a May 2016 trip to the American River. Heading to whitewater raft with the Outdoor Writers Association of California (OWAC), sponsored by Placer County Visitors Bureau, we admired the forested canyons where it once flowed wild before the gold diggers. Salmon used to spawn upstream into the turquoise pools surrounded by white ash and honeysuckle of the Auburn State Recreation Area, as water ousel, a dark-colored water bird, flitted about.

The gold miners invaded the hills and turned them “treeless, mud-laden, turgid, filthy, and fishless,” according to Myron Angel in 1882. The canyons have bounced back, but dams continue to moderate the wild freedom flow, and the proposed but unlikely Auburn Dam still looms over the Middle Fork of the American. Yes, drought- or flood-reactive politicians regularly tout the $6 billion Auburn Dam, the zombie project originally green-lighted by a dam-friendly congress in 1965. With a proposed reservoir of 2-million acre-feet of water, about half the volume of Shasta Lake, it could water a lot of almond orchards or rice fields in the Central Valley. If we decide our need for almonds and rice outweigh our love of wild rivers and fish populations.

***

We launched for a 16-mile Middle-Fork of the American river-rafting expedition with Tributary Whitewater Tours from the Oxbow Powerhouse. Four OWAC members, Steven T. Callan, Kathy Callan, Ron Erskine, and John DeGrazio, donned our wetsuits, life jackets, paddles, and helmets with Alex Boesch from Visit Placer recording in video, all captained by Chris Reeves from Tributary.

My Montana cousin compares river-rafting to riding a bus through Class III and IV rapids, while his preferred kayak more resembles a Porsche. Here’s to say, I’ve traveled all manner of buses on six continents, and never quite had the same experience. Here we come.

Immediately we faced roiling cold water splashing over cobbles deposited from the Pleistocene glacier melt, strewn about by placer (stream bed) mining operations from 1849 onward. Immediate rapids and rock mazes wake us to the reality that white water creates its own entropy over vertical rock foliation and veins of shiny white quartz.

Rapid names like “Guide Slammer,” turbulence over boulders of “Helter Skelter,” razor-back rocks at “Jake the Ripper,” and the real danger of “Last Chance” or “Suicide Drop” pretty much speak for themselves. If your guide, yelling at you to paddle, misses the eddy and gets swept into the next roiling miasma, “Tunnel Chute,” hello Class V rapid through a narrow slot facing sharp dagger rocks on both sides.

Tunnel Chute, a rapid created in the 1890s by ambitious Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece, diverted the entire river through blasting and chipping so they could pilfer the goods from the Horseshoe Bar around the next corner. It has become a premiere notorious feature for whitewater enthusiasts in this part of the northern Sierra Nevada.

Running this rapid left either everything or nothing to chance. Our guide, Chris, though very experienced, was on his first run of this stretch for the year, and expressed a joking apprehension. He quickly proved his mettle.

When he gave the call to pull our paddles and lean in, we held on and tucked our feet under the rubber folds, and pow, bam, spin left, bounce right, ice cold hydraulically-charged water splashing in our faces, we bumped past boulders as the funneled river drops 18 feet in a vicious snarling violent man-made rapid. As geologist William H. “Terry” Wright, PhD, wrote, “By taming the river, the miners of the past made wild river trips of the present more wild.”

At the bottom of jagged walls blasted from black slate, the raft (bus) plunges into a hole and pops up, floating innocently again. It spins ‘round in after-chop and we have a dazed moment of reflection. What the hella we got into?

httpvh://youtu.be/JYZNjzystog

2011 Adventure: Middle Fork American River Whitewater Rafting with GoPro. One could surmise here the guide made some key mistakes, but things can go awry even with the best.

***

Interesting thing about dam builders is their rationale tends not to hold up to scrutiny, which is why many rivers in the US have been set free from their concrete barriers. Take note of the Elwha River on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington, and remember it’s given subtitle: Roaring Back to Life.

STORY: DamNation: On Dam Removal, Salmon and Wild Flowing Rivers

Maintenance and repair costs from trapped sediment and cracking infrastructure have escalated; dams block fish migration, reduce populations, and impact both terrestrial and aquatic endangered species; dams flood sacred sites, sensitive habitats, recreational areas, and towns and villages; as well, dams slow, warm, and dewater river flow, degrading water quality and downstream wetland areas already facing increased climate-change-induced drought and heat.

For every positive story like the Elwha, we have 90,000 existing dams greater than six feet blocking US rivers. The push to remove four dams on the Lower Snake River in Washington has created lots of controversy.

In addition to heating the downstream river temperatures and block beneficial sediments (silt, gravel, cobbles, etc) from replenishing the flows into the Columbia River side channel and coastal wetland habitat for salmon rearing, they also provide warm water refugia for invasive and non-native species to prey on and compete with the native salmon. Using salmon hatcheries and barging fish around the dams only serve to impair wild salmon genetics, evolution, adaptation, and long-term survival and recovery.

Moreover, energy- and water-focused governmental entities continue to propose new dams despite all the problems. The Lower Colorado, the nearby Sierra Nevada Bear River, and Washington’s Lower Fork of the Skykomish all have significant threats from new dams.

In fact, a global boom in dam construction is under way. The emerging economies of Africa, Asia, and South America plan to construct at least 3,700 major hydropower dams, according to a paper published in Aquatic Sciences in 2015 by Christiane Zarfl and A.E. Lumsdon at the Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries in Berlin.

Moreover, researchers found that far from being an inexpensive, carbon neutral source of renewable energy, reservoirs produce methane from decomposing organic matter, and cut trees and constrained flows would be a disaster for river and land health. Free-flowing rivers are, after all, the best defense against climate change, and the future of power generation remains with solar and wind, coupled with efficiency and conservation.

***

The seeming-wild Middle Fork of the American feels endless when our guide again calls out: “Paddle!” We trundle swinging around massive boulders and toward more Class IV flow. Onward to Kanaka Falls, and at this point I knew this was not a sport for the faint-of-heart. We bounced through the rapid, told to lean in and pull our paddles, going into a six-foot drop, the next thing I see my oar-mate Ron Erskine flipped overboard, turned into a “swimmer.” We quickly heaved him back up, but almost lost Kathy too but for quick work by her husband Steve.

Not for the faint. Probably not for me. But there I was.

Class IV Chunder and Ruck-A-Chucky Rapid and Falls lay ahead, and the latter thankfully would be navigated by our fearless captain, Chris. Watching mid-portage from a cliff side, it seemed he handled the house-size rocks and 35-foot drop, but we could not see him lose control of the raft and plunge over the falls sideways, landing barely upright in the roiling Lower Ruck-A-Chucky. Green bedrock, hard metamorphosed volcanic lava flows, ash tuffs, and broken breccias make this a deadly passage, but we hop back in and keep it moving, telling ourselves this was no big deal.

STORY: Old Town Auburn, Portrait of a Gold Rush Town

httpvh://youtu.be/VwSiDnf_44Q

The famed Ruck-a-Chucky Class IV Rapids and Falls

Downriver a stretch, somewhere in the Class III of Texas Chainsaw-Mama, staring at an imposing boulder dubbed Mike Tyson, Chris called us to lean-in. Ducking, feet dug-into the raft and holding-on to the ropes, the raft pitched and accordioned against the rocks, tossing Ron asunder once again. Chaos ensued, as my tuck rendered me immobile for those seconds, raft-mates yelling and splashing-cold danger confronted us. Tyson menaced and seconds of gulping and gasping, while John DeGrazio leaped over the seats to yank Ron with life-vest-straps to safety.

We all cheered. Raft people dope on adrenaline, the sun glinted off a whirlpool, cold dousing woke and dazed me, as the river had us in its flow-cupping hands.

Stopping the Auburn Dam made this communion with the wild splash of the American possible. This year, after one of the biggest snowpacks ever recorded, the rivers are aflowing, and the insanity of whitewater lures the speed- and risk-enthusiasts with greater challenges and faster runs. They say earthquake risks finally sunk the proposal. We hope the benefits of letting rivers free like the Elwha will speak to the many in government and commerce, restoring floodplains and fisheries, and allowing rafters and kayaks the thrill of their lives.

Trip with the Outdoor Writers Association of California (OWAC), sponsored by the Placer County Visitors Bureau. Thanks to the Holiday Inn Auburn for hosting the conference, as well as Tributary Whitewater Tours, and High Hand Nursery and Cafe.

Source

The Wilderness Conservancy, The American River, North, Middle & South Forks, Protect American River Canyons (PARC), Auburn, CA. 1989. Section by William H. “Terry” Wright, PhD.

Updated 8 May 2019

Pingback: Old Town Auburn, Portrait of Gold Rush Town | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Wild Sonoma's 'Valley of the Moon' - Living with the Land | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Dam-Free: How Indigenous Peoples Reclaim the Klamath River

Pingback: Panama Hydroelectric “Clean Energy”: Village of the Dammed

Pingback: The Edge of Yosemite Comes Alive in Tuolumne County