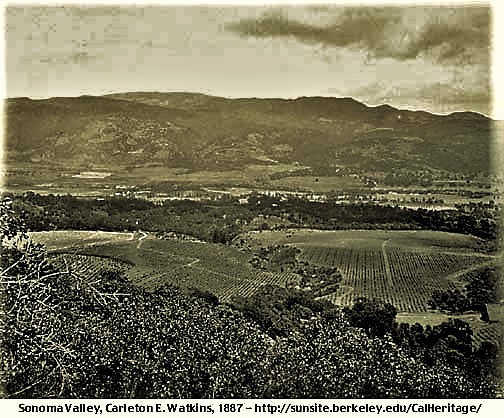

Sonoma County in Northern California is known for it’s world-class wine, gentle hills, and temperate climate, where novelist-gentleman-farmer Jack London set up his ode to wild sustainability one hundred years before it became a thing. The Pomo, Coast Miwok, and Wintun peoples knew Sonoma in legends as the ‘Valley of the Moon’, which London used to title one of his books. Flying over in a hot air balloon, hiking the protected hillsides to find a precious Pinot Noir at one of the 425 wineries, sailing off the coast, there are many ways to get lost in them hills.

Sonoma County Vision of Sustainability, Yesterday and Today

“Hawk and coyote thought a long time about the darkness. Then Coyote felt his way into a swamp and found a large number of dry tulle reeds. He made a ball of them. He gave the ball to Hawk, with some flints, and Hawk flew up into the sky, where he touched off the tulle reeds and sent the bundle whirling around the world.” — From ‘Origin of Light‘, a Gallinomero Legend

I’m not a person inclined to ride in a gas-powered hot air balloon. I prefer to keep myself connected to the ground, but while in the Sonoma Valley a while back I had a chance to jump on an early morning Up & Away liftoff from a field near the Charles M. Schulz airport in Santa Rosa. From the vantage of a hawk, the possibilities of environmental sustainability can be gleaned across the rolling green landscape of river valley, vineyards, and forested mountains in the distance. A survey of historic conservation efforts becomes relevant for the future of a region recovering from the catastrophic climate-change-drought-fueled Tubbs wildfire of 2017.

***

Sonoma’s sustainability vision started with the Pomo people, which included seven different ethno-linguistic groups, with some of the tribes and bands clustered in the region of the headwaters of the Russian River all the way down to the estuaries at the coast. Traditional regional inhabitants who subsisted on fishing, hunting, and gathering also included the Coast Miwok, Wappo, and Wintun as well as other bands with different names, identities, and histories of settlement dating back to 8,000 BC.

Peoples thriving and cohabiting in a region for 10,000 years must have been doing something right: living within their means, using only what they could get, letting the land and water dictate carrying capacity.

One of the Pomo tribes called the Gallinomero told a story called “The Spirit Land,” where after bodies of their dead were burned, they scattered the ashes into the air and land. The good spirits manifested into the coast redwood forests, lakes, and river valleys, and a paradise across the Big Water. The bad spirits went off into an island in the Bitter Waters, to work it off and try and get it right.

STORY: Eye of God: Big Bear’s Sacred Site of Creation

About 90 percent of these original inhabitants were devastated by invading Europeans and their diseases and land dispossession in the Nineteenth Century. This thriving society ended with the founding of the San Rafael Arcángel Mission in 1817 and the San Francisco Solano Mission in 1823, and only a portion of that population rebounded since amid the pastures and agricultural fields that replaced their former forage and hunting fields.

We are still grappling as a culture with how to reconcile the wonder that is Native California, with what we have built in the last couple of hundred years, but in Sonoma much of the beauty of the land remains.

***

We all gripped the basket as the balloon floated gas-deflating down toward a soft-landing in a field of green flowering grasses. I felt an immediate embrace from the land, a welcoming back, and a call toward regeneration with the good-spirit influences that guided the 10,000-year-tenure of indigenous care and subsistence of this landscape.

Vineyards, Wine, and Jack London’s Sustainable ‘Beauty Ranch’ in the Valley of the Moon

A group of us gathered at the Madrone Estate at the Valley of the Moon Winery to taste Sonoma Valley’s main export and hike through the vineyards, organized by an innovative and engaging couple who runs Wine Country Trekking. We discussed biodynamic wine-making using organic fruit and post-harvesting processing, employing Rudolf Steiner’s soil supplements, compost, and astronomically-influenced plantings, and of course Jack London’s early local farming efforts came up.

The famous author and journalist Jack London (1876-1916) grew up on the rough Barbary Coast streets of San Francisco and the wild side of Oakland in the late 1800s – but he was also a farmer, and an early adopter of the philosophy of environmental sustainability when he came to Sonoma County.

He wrote prolifically and in 1903 at age 27, hit the big time with The Call of the Wild and White Fang, both still considered classics set in the Klondike Gold Rush. A member of a radical literary group, “The Crowd” in San Francisco, he was a passionate advocate of unionization, socialism, and the rights of workers. Around 1906 he and his second wife Charmain bought the 1,000-acre ‘Beauty Ranch’ in Sonoma County, near the village of Glen Ellen, as an escape from city life where he could commune with the land and develop his ideas for sustainability.

The land had been heavily farmed by the original settlers and the soil was exhausted. London, still a young man at 30 years old, began reading voraciously about natural farming techniques, a topic not popular at the time. He had covered the Russo-Japanese War in 1906, and also visited Korea, where he learned about terraced farming and natural fertilizers.

STORY: On Wild Rivers, Hydroelectric Dams, and Whitewater Rafting the American

He jumped into agriculture with the same energy and dedication he still gave to his writing, and experimented with organic farming and animal husbandry, and put into practice controlled animal grazing, use of green manures, crop rotation, recycling animal and plant waste via composting and natural fertilizers.

In 1915 he created the ‘Pig Palace’ (a term unsympathetic journalists used to mock his innovative idea) where his prized Duroc-Jersey hogs were allowed to roam in their own private indoor/outdoor pens, basking in the sunshine if they chose. This pig-pen was also created with a circular, central feeding tower so one person could maintain all 17 pens – thereby reducing the required labor force needed to maintain close to a hundred animals.

“The proper function of man is to live, not to exist. I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them. I shall use my time.” — Jack London

Yes, Jack London was a multi-tasker who continued to travel the world and write about it, so he might not have focused enough on managing costs and follow-through with his farming operations. He also faced significant health challenges, so his living experiment in sustainability encountered a wall of fire when his elaborately planned and designed Wolf House went up in flames in 1913.

***

Wildfire further consumed the dreams of many Sonoma County residents in 2017. When we finished our wine-trekking tour at B.R. Cohn Winery, founded by the former Doobie Brothers manager Bruce Cohn, and site of the Sonoma Harvest Music Festival, surrounded by photos of generations of rock-n-rollers imbibing wine, the conversation touched on the fear of the future of wild places. The slope well-beyond the winery had burned in the 2017 fire, but firefighters held off the flames at a distance. We all agreed that when it comes to confronting climate-chaos induced diablo-wind-driven wildfire threats, preparation and planning come first. Yet, some people and places are better prepared than others.

Living Lightly on the Land in a Time of Drought, Wildfire, and Climate Change

Sonoma, like so many places in the Western U.S., faces the challenge to too many flammable homes, built into a flammable landscape facing increasing heatwaves and droughts from climate change. In addition, the natural fire and water cycles have been suppressed for so long, and a series of giant conflagrations await. The devastation of the Fountaingrove II community in Santa Rosa during the 2017 Tubbs Fire was predictable. The city was warned this area was too dangerous to place homes. The area had burned in a wind-driven fire in 1964. In 2001, the city’s planning division issued a report concluding the development did not properly follow the city’s General Plan’s goals and policies.

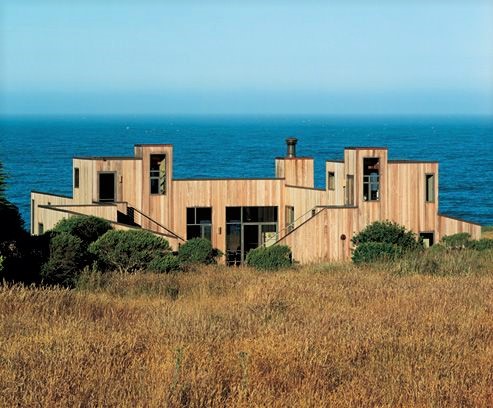

It is possible to live with the land, integrated into the native vegetation, despite the dangers. Take a page out of the original vision of the Sea Ranch in Sonoma County. Proposed in the 1960s, the ensuing battle for coastal access gave rise to the legislation that formed the Coastal Commission. The creation sought to assimilate with the elements, rather than confront them, codifying a covenant with nature.

Set on a misty 10-mile stretch of Sonoma coast, Sea Ranch is a community drawn together by a unique shared vision and respect for its concept, an early example of ecological planning. The founding ideal, shaped by the all-star cast of architects, was that the land should be shared rather than subdivided, a dynamic form of conservation or “living lightly on the land.”

The early architecture was communal and modest, with houses clustered perpendicular to the ocean so that everyone would have a view, leaving the meadows open and held in common. Houses were sited to settle into the landscape, like quail nesting. Landscape Architect Lawrence Halperin designed the master plan based on his experiences in a kibbutz, of open land held in common and homes sited in deference to nature.

Architect Charles Moore called the Sea Ranch his Mother Earth, and created the ground-breaking Condominium One. Obie Bowman designed the Walk-in Cabins, a remote gathering of 15 Hobbit-like dwellings in a kingdom of redwoods in the hills above Highway 1, where no cars are allowed. They are left about a quarter-mile down a dirt road.

Arguably, Sea Ranch’s most hallowed ground are the Hedgerow Houses, a group of genteel rustic shacks, some as small as 1,000 square feet, that designer Joseph Esherick tucked inconspicuously into a row of wind-blown cypress trees not far from Black Point Beach.

Unfortunately, many of these concepts have been lost in subsequent planning and sacrifices to the real estate and political interests. By the late 1990s, the area has become suburbanized, but still retains the general outline of the original plan.

***

We ended our visit back at Jack London’s Beauty Ranch preserved forever as a State Historic Park, despite the dreams that went up in smoke, and considered the need to regenerate nature, rather than despoil it. In these times of serious threats to life and land from our culture’s and economy’s profligate ways, walking lightly is the order for the day.

Trip with the Outdoor Writers Association of California (OWAC), sponsored by the Sonoma County Tourism and planned by SoEventful. Thanks to the Flamingo Resort in Santa Rosa for hosting the conference, as well as Wine Country Trekking, Up & Away Hot Air Ballooning, Calistoga Balloons, Shed Grange, Madrone Estate, B.R. Cohn, and of course Jack London State Historic Park.

Updated 22 December 2023

Pingback: Communal Utopia: The Farm in Rural Tennessee