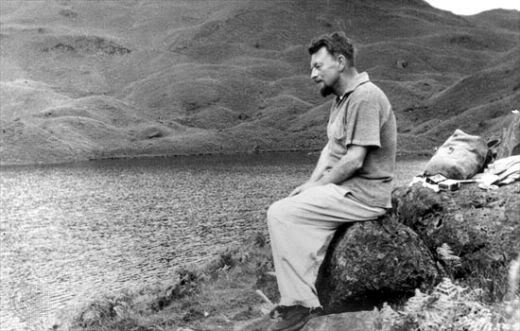

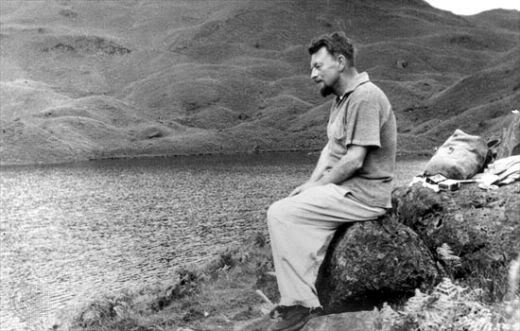

Malcolm Lowry’s 1947 masterpiece Under the Volcano, about the fervid last hours of an alcoholic ex-diplomat in Mexico, is set to the drumbeat of coming internal and external conflict. Autobiographical and reflective of the expatriated trust-funder in a futile search for an artistic home, the perpetually inebriated master got lost along the road toward his own abyss, and died under suspicious circumstances, out-of-print.

The 100 best novels: No 68 – Under the Volcano by Malcolm Lowry (1947)

By Robert McCrumb, Published in The Guardian

It is November 1939, the Day of the Dead in Quauhnahuac, Mexico. Two men in white flannels, one a film-maker, are looking back to last year’s fiesta. It was then, we discover, that Geoffrey Firmin – the former British consul, ex-husband of Yvonne, a rampant alcoholic and also a ruined man – embarked on his via crucis, an agonized passage through a fateful day, that would end in Firmin’s killing.

Lowry himself, a refugee from the London district Fitzrovia of his contemporary George Orwell and the young Dylan Thomas, described Under the Volcano as “a prophecy, a political warning, a cryptogram, a preposterous movie, and a writing on the wall.” At the back of his mind, he was inspired by Melville (No 17 in this series) and the capacious majesty of Moby-Dick. Lowry’s Captain Ahab, however, is fighting a more nebulous nemesis than a whale. In 12 chapters corresponding to the 12 hours of the consul’s last day on earth, Lowry takes Firmin on a colossal bender, fuelled by beer, wine, tequila and mescal (“strychnine” to our protagonist). He is drinking himself to death, like Lowry himself, though Under the Volcano is about much more than alcoholism. Halfway through, the consul decides that “It was already the longest day in his entire experience, a lifetime.” Formally, then, the novel’s narrative technique owes a huge debt to Joyce, Conrad, and Faulkner (Nos 46, 32, and 55 in this series). Lowry’s text also teems with allusions to classical and Jacobean tragedy, echoing the cadences of Christopher Marlowe and the Elizabethans.

“Perhaps his tragedy is that he is the only normal writer left on earth — and it is this that adds to his isolation and so too his so sense of guilt.” — Malcolm Lowry

One of mescal’s side-effects is a highly lucid, almost brilliant, depression: this is a dominant mood throughout much of Lowry’s introverted, strangely compulsive narrative. Again and again, he insists that he is present in all his characters, an assertion of complex consciousness that is also a deranged kind of solipsism provoked by tropical drink and drugs. We are in the Mexico that attracted many interwar English literary travelers, notably Lawrence, Waugh and Greene, but it’s a Mexico that has become a hell on earth.

The background to the consul’s Day of the Dead is the drumbeat of conflict, both public and private. Germany is re-arming. Yvonne, Firmin’s divorced wife, has come back to challenge his drinking. “Must you go on and on forever into this stupid darkness?” she asks. At the edge of darkness there is death. Under the Volcano began in Lowry’s mind when, arriving in Mexico, he saw a local Indian bleeding to death by the roadside, which is how Firmin will end, shot in a cheap bar before being tossed into a ravine with a dead dog. The last moments of the consul at the end of the “Day of the Dead” (chapter 12) become one of the greatest passages of English prose on the eve of the second world war.

“Try persuading the world not to cut its throat for half a decade or more…and it’ll begin to dawn on you that even your behavior’s part of its plan.”– Malcolm Lowry, “Under the Volcano”

STORY: B. Traven’s “Macario” – Magical Realist Journey on Day of the Dead

Watch this video on YouTube

Volcano: An Inquiry into the Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry, with Richard Burton reading from Lowry’s works, and Directed by Donald Brittain & John Kramer – 1976

A note on the text

No writer in this series had as much trouble as Malcolm Lowry, from inside and out, with his work-in-progress. For the struggling author, in the making of his masterpiece, over nearly a decade, almost nothing went right. At first, in 1936, living in Cuernavaca, Mexico, in the shadow of two volcanoes (Popocatépetl and Iztaccihuatl), galloping alcoholism and a failing marriage, Lowry wrote a short story (not finally published until the 1960s) entitled “Under the Volcano,” a sketch of the bigger canvas that was to follow, including a horse branded with the number seven.

“Under the volcano! It was not for nothing the ancients had placed Tartarus under Mt. Aetna, nor within it, the monster Typhoeus, with his hundred heads and—relatively—fearful eyes and voices.” — Malcolm Lowry, “Under the Volcano”

The first, raw draft of Under the Volcano followed soon after. He considered this to be the “Inferno” element of a trilogy, The Voyage that Never Ends, modeled on Dante’s Divine Comedy. Ultimately, fate determined that only the first part of this ambitious project would ever be completed to its author’s satisfaction. In 1940, Lowry commissioned a New York literary agent, Harold Matson, to find a publisher for this manuscript, which was roundly rejected, up and down Manhattan.

Next, between 1940 and 1944, Lowry revised the novel, with crucial editorial assistance from the actress Margerie Bonner, who saved him from the worst of his alcoholism and later became his second wife. This process absorbed him completely: during those years Lowry, who had previously preferred to address himself to several projects at the same time, worked on nothing but his manuscript. In 1944, the current draft was nearly lost in a fire at Lowry’s beach house (a squatter’s shack) in British Columbia. Bonner rescued the unfinished novel, but the rest of Lowry’s works in progress were consumed in the blaze.

“Ah, the harbour bells of Cambridge! Whose fountains in moonlight and closed courts and cloisters, whose enduring beauty in its virtuous remote self-assurance, seemed part, less of the loud mosaic of one’s stupid life there, though maintained perhaps by the countless deceitful memories of such lives, than the strange dream of some old monk, eight hundred years dead, whose forbidding house, reared upon piles and stakes driven into the marshy ground, had once shone like a beacon out of the mysterious silence, and solitude of the fens. A dream jealously guarded: Keep off the Grass. And yet whose unearthly beauty compelled one to say: God forgive me.” — Malcolm Lowry, “Under the Volcano”

The novel was finished in 1945 and immediately submitted to a number of publishers. In late winter, while still travelling abroad, Lowry heard that his novel had been accepted by Reynal & Hitchcock in the United States and Jonathan Cape in Britain. Cape had reservations about publishing and asked for drastic revisions. He added that if Lowry didn’t make the changes “it does not necessarily mean I would say no.” Lowry’s reply, written in January 1946, was a prolonged, vehement, slightly mad defense of the book as something to be considered a work of lasting greatness: “It can be regarded as a kind of symphony,” he wrote, “or in another way as a kind of opera – or even a horse opera. It is hot music, a poem, a song, a tragedy, a comedy, a farce and so forth … Whether it sells or not seems to me either way a risk. But there is something about the destiny of the creation of the book that seems to tell me it just might go on selling a very long time.”

“Somebody threw a dead dog after him down the ravine.” — Malcolm Lowry

Watch this video on YouTube

Clip from Under the Volcano, a 1984 film by John Huston, starring Albert Finney and Jacqueline Bisset.

Cape published the novel without further revision. To Anthony Burgess it was “a Faustian masterpiece.” Yet, Under the Volcano was remaindered in England, and out of print when Lowry died of “alcoholism,” under suspicious circumstances (that he might have been murdered by his wife), in 1957. The coroner labeled it “Death by Misadventure.” Thanks to a better response in North America, especially Canada, its afterlife has been lusty and international, featuring regularly on several “best novels” lists. Now it’s recognized as a classic.

Three More From Malcolm Lowry

Ultramarine (1933); Lunar Caustic (1968); October Ferry to Gabriola (1970).

Robert McCrum is an associate editor of the Observer. He was born and educated in Cambridge. For nearly 20 years he was editor-in-chief of the publishers Faber & Faber. He is the co-author of The Story of English (1986), and has written six novels. He was the literary editor of the Observer from 1996 to 2008, and has been a regular contributor to the Guardian since 1990

Pingback: B. Traven: Underground Anarchist In The Jungle | WilderUtopia.com