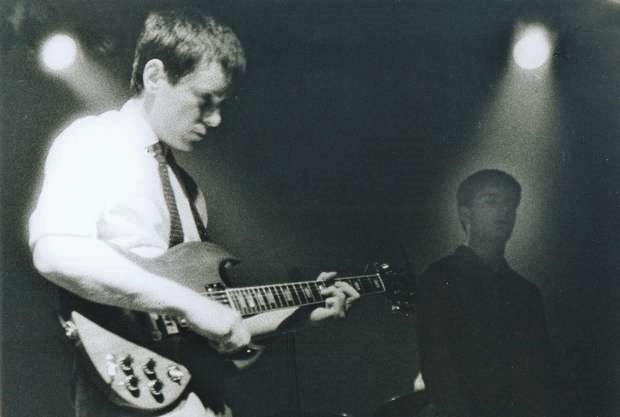

As bassist for Joy Division – one of the most important bands of the post-punk movement in England – Peter Hook kept the rhythm together, a kind-of-distorted lamentation, after Ian Curtis’ suicide and for better or worse into mega-stardom of the New Wave synth-pop phenomena New Order.

We Were Joy Division

By Peter Hook, Published in The New York Times

It all started with the Sex Pistols. I saw them twice in 1976 — two gigs weeks apart at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester — Bernard Sumner (our guitarist) and I went together with a couple of friends to the first gig, and at the second gig I bumped into Ian Curtis, who would become our lead singer. They were only on for half an hour, but when they finished, we filed out quietly with our minds blown, absolutely utterly speechless, and it just sort of dawned on me then — that was it. On the way home that night we decided to form a band — Joy Division. The name was Ian’s idea.

[Note: The original band was called Warsaw, but due to a conflict changed the name to Joy Division, derived from the World War II era German derisive term for Jewish women forced to be sex workers (unpaid) servicing both the military and concentration camp guards.]

httpvh://youtu.be/GqUFbd8aAN0

By 1979, we hadn’t yet even made an album, but because we were being so productive, talk turned to making one. To be perfectly frank, we weren’t that fussy about whom we made it with. But in the meantime Martin Rushent invited us down to the studio to record some demos, just to see if we were going to jell. He’d produced the Buzzcocks and the Stranglers by this point, so we were very excited by the prospect.

When we got there, we saw that Rushent had a brand-new Jaguar XJS — and as it happened I’d been reading this article about how something like 9 out of 10 Jag owners don’t lock the boot of their car. So I thought, I wonder if that’s true. . . . Tried his boot and, lo and behold, it was unlocked. Inside, it was full of what I’m sure were stolen car radios; you could tell they were stolen by the way the wires were dangling off from where they’d been ripped out. Me and Terry, our roadie, were looking at each other, thinking, Martin’s got a boot full of stolen car radios. And then, Wonder if he’d miss a couple. . . .

All day, whenever there was a break in the recording, we’d be daring one another to go back in his boot and nick one each for our cars — because they were proper high-end stereos — but I was going: “Oh, no, we can’t, because he might be our record company. We can’t nick cassette players off our record company.” We didn’t take any. God knows what he was doing with them, though. We never asked him.

These are your friends from childhood, through youth,

Who goaded you on, demanded more proof,

Withdrawal pain is hard, it can do you right in,

So distorted and thin, distorted and thin.Where will it end? where will it end?

Where will it end? where will it end?— Joy Division

STORY: Art of Black Flag: Angst and Rebellion Symbolized

httpvh://youtu.be/zsHoOIHDutE

Joy Division – She’s Lost Control – Live at BBC2 “Something Else” 09/15/1979

It was a really nice studio, and he worked well with Ian on the vocals, did a few overdubs and stuff, nothing wild, very low key. The tracks were “Glass,” “Transmission,” “Ice Age,” “Insight” and “Digital.” Rushent was a nice guy; we got on well.

That was the thing about Joy Division, though: writing the songs was dead easy because the group was really balanced. We had a great guitarist, a great drummer, a great bass player and a great singer. Ian would listen to us jamming and then direct the song until it was . . . a song. He stood there like a conductor and picked out the best bits. Which was why, when he killed himself a year later, it made everything so difficult. It was like driving a great car that had only three wheels. The loss of Ian opened up a hole in us, and we had to learn to write in a different way. We were so tight, as a group, we didn’t even use a tape recorder half the time. Didn’t need one.

For all the well-documented aural and thematic fragility of Joy Division, their greatest impact likely lies in the powerful catharsis of their music. Paired with the mournfully kinetic sounds created by Hook, Sumner, and Morris, the baleful tone from Curtis purges any semblance of superficiality with an emotional delivery that’s disturbingly believable. — Jonathan Dick

Back then we didn’t know rules or theory. We had our ear, Ian, who listened and picked out the melodies. Then at some point his lyrics would appear. He always had these scraps of paper that he’d written things down on, and he’d go through his plastic bag. “Oh, I’ve got something that might suit that.” And the next thing you knew he’d be standing there with a piece of paper in one hand, wrapped around the microphone stand, with his head down, making the melodies work. We’d never hear what he was singing about in rehearsal because the equipment was so terrible. In his case it didn’t matter because he delivered the vocal with such a huge amount of passion and aggression, as if he really meant it.

I recently got offered the tape of that session with Rushent. Eden Studios was taken over by a firm of solicitors, and left in a storeroom, hidden in the bowels of it, were the Joy Division masters. One of the staff members claimed to have them and offered me the tape through a third party. He wanted £50,000 for it. This was in 2006 or something. Even then there was no way on earth you could make a record and hope to recoup 50 grand. I offered him a finder’s fee, two grand, but he said no, and I’ve never heard from him since; it’s never appeared. Ah, well. It’s a funny thing, people trying to sell you back bits of your own past. But I’m getting used to it, to be honest.

Peter Hook is a co-founder of the bands Joy Division and New Order. This essay is adapted from his memoir, “Unknown Pleasures,” published in 2013 by HarperCollins.

Jonathan Dick’s essay: Stereogum

Watch this video on YouTube

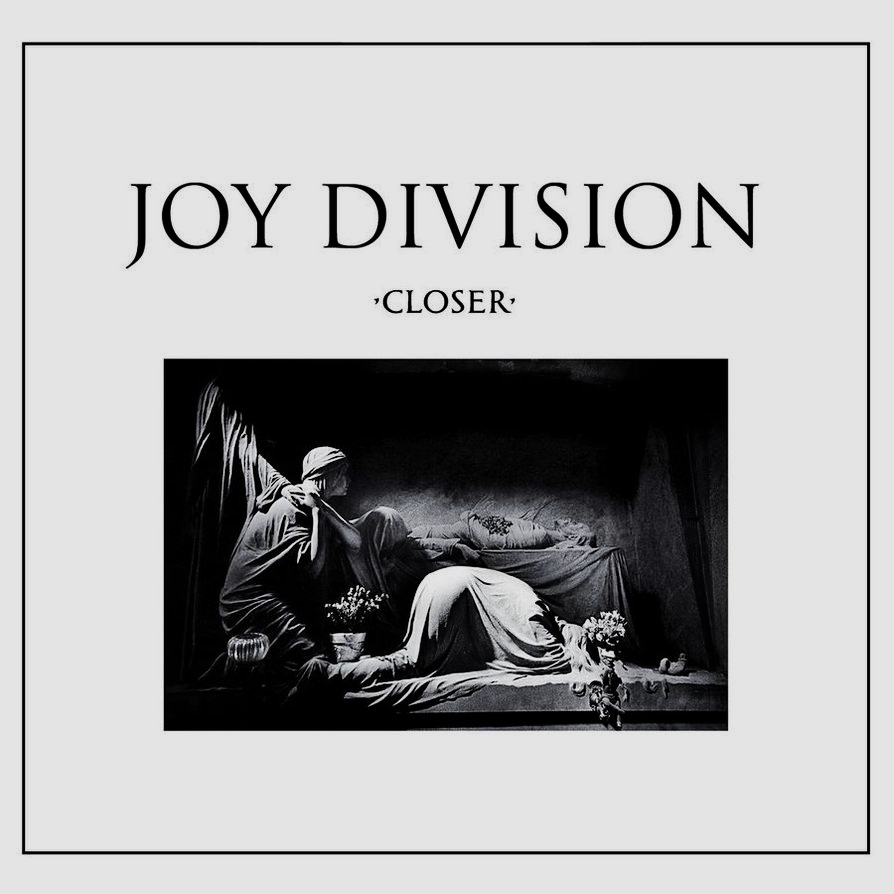

Joy Division: Heart and Soul, from Closer.

Pingback: Tribute to SomaFM's Darkwave channel 'doomed' | WilderUtopia.com