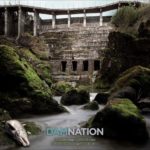

How two bitter opponents, Barry Goldwater and David Brower, came to realize the folly of dam building and desert over-development in the arid Southwest United States. It is time to open the floodgates of Glen Canyon Dam.

Goldwater, Brower and the disastrous damming of the Colorado River

By Paul VanDevelder, Published in The Los Angeles Times

As all eyes in the West look to the courts, the skies and the Colorado River for relief from 14 years of drought, it might be useful to remember the battles waged by two titans of the 20th century who played leading roles in the drama that led to the current mess.

The first protagonist was Arizona’s favorite son, Sen. Barry Goldwater. His nemesis was the fearless environmental crusader, David Brower, a founder of the Sierra Club known to those who loved him as The Archdruid. Early in their parallel careers, these two men were fierce adversaries over water projects across the Southwest. By the end of their lives, however, the tables had turned in the most unpredictable of ways.

There is no shortage of water in the desert but exactly the right amount, a perfect ratio of water to rock, of water to sand, insuring that wide, free, open generous spacing among plants and animals, homes and towns and cities, which makes the arid West so different from any other part of the nation. There is no lack of water here, unless you try to establish a city where no city should be. — Edward Abbey, “Desert Solitaire“

During the boom years for damming American rivers, no politician was a bigger believer in the transformative power of impounded water than Goldwater. He was the Bureau of Reclamation’s best friend in Congress whenever the agency proposed mind-boggling water projects such as the Glen Canyon Dam.

While Goldwater and the reclamation bureau were enjoying a golden age for water projects, Brower battled to stop many of Goldwater’s pet endeavors. Most notably, Brower led an unsuccessful national campaign to stop Glen Canyon Dam, which created Lake Powell in northern Arizona. Brower called his defeat on Glen Canyon “the darkest day of my life” and vowed it would never happen again. It didn’t.

The Paiute were a Water People, who viewed the entire Grand Canyon as something holy. To find their way through its depths they relied on a repertoire of hundreds of songs, each a melodic road map through a sacred homeland known to them as Puaxantu Tuvip, words that implied a landscape vibrant and alive, responsive in a thousand ways to human needs and aspirations. — Wade Davis, “River Notes“

Time and old age have a way of bringing people to their senses. In 1997, PBS aired the documentary “Cadillac Desert,” based on Marc Reisner’s book of the same name. In the third of four episodes, Goldwater and Reisner discussed the adjudication of the Colorado River, and the silver-haired paragon of American conservatism revealed a remarkable change of heart. Looking out across the sprawling megalopolis of Phoenix, he asked Reisner a pair of rhetorical questions that clearly pained him: “What have we done to this beautiful desert, to our wild rivers? All that dam building on the Colorado, across the West, was a big mistake. What in the world were we thinking?”

httpvh://youtu.be/Mis-CU9oZO0

Cadillac Desert – An American Nile, Water and the Transformation of Nature (1997) – A Four-Part Mini-Series about water, money, politics, and the transformation of nature.

A few months later, I had lunch with Brower and asked him what he made of Goldwater’s change of heart. Brower was then in his late 80s but just as fierce as ever, if not more so. He cackled with an expletive. “I reached for the phone and called him! And he answered, and I said, ‘Barry, this is David Brower; what do you say we do the right thing: help me take out Glen Canyon Dam.'”

The Archdruid looked at me, eyes twinkling with green fire. “He said he would; he said that was a grand idea. Then he died a few months later.”

And Brower died not long after that.

The marshes and lagoons of the Colorado delta had for thousands of years been home to the Cocopah Indians, who viewed themselves as offspring of mythical gods, twins who had emerged from beneath the primordial water to create the firmament, the earth, and every living creature. In 1540 Hernando de Alarcon encountered at the mouth of the river not hundreds but thousands of men and women, who, in their rituals, he reported, revealed a deep reverence for the sun. — Wade Davis, “River Notes”

In many respects, trouble with the Colorado began long before Goldwater and Brower fought over Glen Canyon. The trouble with the Colorado, and any other river, for that matter, is that nothing in nature is static. Flow rates, based on historical data, are inevitably flawed. When the Colorado’s water was divvied up between the states and Indian tribes in the 1960s, the math was based on hydrologic fictions. The river’s annual flow was overestimated by millions of acre-feet, and taking out Glen Canyon Dam would not change that by one drop. The nation had fully invested in the vain belief that we could dam its way out of aridity and drought, and it had built up the desert based on that faith.

Nevertheless, taking out Glen Canyon Dam would make a resounding statement. It would say: Wild rivers rock. It would say: “We should have left well enough alone; we should have listened to John Wesley Powell and limited settlement on arid lands.”

Because of its location in the desert amid porous geology, Lake Powell causes huge evaporation and seepage losses, 6-8% of the Colorado River’s flow.

Like all dams, Glen Canyon traps silt, but because the Colorado is an especially high-sediment river, the dam has posed even worse consequences for the river between it and Lake Mead (essentially, the Grand Canyon). With drought intervening, the dam may not be able to release water due to the blockage of the river outlets and penstocks. The Colorado below the dam would be reduced to a trickle, causing unprecedented loss of riverine life. As well, the Colorado through Grand Canyon now lacks the source of sediment it needs to build sandbars and islands, debilitating the ecosystem. — Wikipedia

We’ll never see the likes again of Goldwater, Brower and their cohort. Guys like Floyd Dominy and Edward Abbey were men of a time, of an America that no longer exists. We can’t go back to that America any more than we can return to the Indian wars and reverse-engineer the outcomes to create a legacy with less shame, less betrayal, less destructive exploitation. We’re stuck with what we’ve constructed, just as we’re stuck with a long history of terrible water management.

The Colorado River has always been a special case. The drought that grips the Southwest today is the worst in 1,250 years, and climate modeling suggests things are likely to get worse. Ironically, the first state in line to lose water from diminishing reserves is Arizona. Suddenly, those 280 golf courses in the greater Phoenix area, not to mention tens of thousands of swimming pools, look kind of ridiculous. And don’t look now, but guess who’s first in line for the water that would otherwise water those golf courses?

The tribes. Dozens of them: the Fort Mojaves, the Shoshones, the Chemehuevi and Quechan, the Hopi and Navajo, et al. Where water flows between a rock and a dry place, tribes get first dibs.

Karma, it seems, is very patient, and it has its own funny way of asking, “What in the world were we thinking?”

Paul VanDevelder is the author of “Savages and Scoundrels: The Untold Story of America’s Road to Empire Through Indian Territory.”

Copyright © 2014, Los Angeles Times

Pingback: DamNation: On Dam Removal, Salmon and Wild Flowing Rivers | WilderUtopia.com