Sadly, the car-oriented luxury condos and estates, created for the ease of the automobile instead of with an eye toward creating a place for humans to cohabitate with each other and their environment. The inequalities of present day Cairo have sadly been transferred to the planned creations, enforced by an authoritarian government barring public participation, depending upon private development concerns to create the neighborhoods, which always skews toward sterile gated subdivisions with fences to keep the world at bay, green lawns and golf courses to make it all appear beautiful without the downside of admitting it is a desert ecosystem, designed for auto- and fossil-fuel-dependency, giving people limited opportunities to walk and come together in public spaces. -JE

To Catch Cairo Overflow, Magacities Rise in Sand

By Thanassis Cambanis, Published in the New York Times

6 OCTOBER CITY, Egypt — The highway west out of Cairo used to promise relief from the city’s chaos. Past the great pyramids of Giza and a final spasm of traffic, the open desert beckoned, 100 barren miles to the northwest to reach the Mediterranean.

That, at least, was the case until recently. Now, the microbus drivers and commuters driving from Cairo cross 20 miles of nothingness to encounter a new city suddenly springing from the sand. A distressingly familiar jam of cars and a cluster of soaring high-rises herald the metropolis that is designed to relieve pressure on the historic center of Cairo, which city planners have deemed overtaxed beyond repair.

Welcome to the new Cairo, not entirely different from the old one.

Cairo has become so crowded, congested and polluted that the Egyptian government has undertaken a construction project that might have given the Pharaohs pause: building two megacities outside Cairo from scratch. By 2020, planners expect the new satellite cities to house at least a quarter of Cairo’s 20 million residents and many of the government agencies that now have headquarters in the city.

Only a country with a seemingly endless supply of open desert land — and an authoritarian government free to ignore public opinion — could contemplate such a gargantuan undertaking. The government already has moved a few thousand of the city’s poorest residents against their will from illegal slums in central Cairo to housing projects on the periphery.

Few Egyptians seriously expect the government to demolish the makeshift neighborhoods that comprise as much as half the capital, although many critics accuse the government of transferring Cairo’s historical inequalities to the new cities.

But on one point almost everyone seems to agree: it is too late to change course.

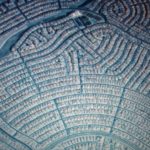

Scott Nelson/World Picture Network, for The New York Times

Enormous subdivisions have sprung up in the dunes outside of Cairo, on an almost incomprehensible scale. Already a million people have moved to 6 October City, due west of Cairo, named for the date of the 1973 war between Egypt and Israel still hailed as a seminal Arab victory. A similar number have moved east of the city, to a settlement unimaginatively dubbed “New Cairo.”

The government’s original plans — which are widely considered more wishful than literal — conceived of 6 October City’s expanding to 3 million by 2020 and New Cairo to 4 million, primarily as havens for working-class Cairenes. So far, however, the overwhelming majority of new residents come from Egypt’s uppermost economic strata.

“These settlements represent the greed of the rich,” said Abdelhalim Ibrahim Abdelhalim, an architect known for incorporating historic Islamic aesthetics into his contemporary public buildings and parks. Mr. Abdelhalim designed the American University of Cairo’s new eastern campus, but he no longer works on elite housing projects.

The Egyptian government has spent untallied millions of dollars building new roads and power and water lines to the desert areas it designated for future development. It has sold huge parcels of land to developers in opaque deals, and built some low-income housing. But it has relied primarily on private developers to put up the cities’ more expensive villas and condos, as well as the malls and offices.

Some of the earliest arrivals in the new cities are affluent Egyptians like Nisrine Alkbeissi, 29, who chose suburban quality of life over urban convenience. “I was torn between staying in Cairo, close to everything, or moving out here,” said Ms. Alkbeissi on a recent weekend at Dandy Mall, a rare public space in 6 October City, a patchwork of luxury compounds and lower-income housing complexes that still is a city in name only.

Her mother had already moved to a nearby gated compound with palm trees and a swimming pool.

“I chose the house with the garden,” Ms. Alkbeissi said, her saucer-size gold filigree earrings flapping as she propped her two-year-old daughter on her lap.

She was hosting two friends who had driven 50 miles for coffee. A few years ago, they lived only a few miles apart but hours away when they factored in Cairo’s legendarily snarled traffic.

Now they drive along the ring road from New Cairo in the east to 6 October City in the west, never once getting close enough even to spot the old city in the distance.

Other pioneers include some of the richest Cairenes, who buy villas on golf courses and in gated compounds. They have been joined by some of the poorest, drawn by factory and construction jobs, or to serve the rich. Other poor people are shuttled in against their will by the government to isolated tracts of row houses.

The juxtaposition of rich and poor highlights one of Mr. Abdelhalim’s greatest concerns. The new cities, he says, tend to highlight Egypt’s already striking imbalance between rich and poor, and could sow the seeds of future troubles.

Consider Haram City, the first affordable housing development here built by a private company. Phase 1 was just completed this summer, and 25,000 people have moved in. When it is complete in two years, Haram City will house 400,000 people — a single project with the population of Miami.

Although it was designed for lower-income workers, some of Haram City’s first residents are indigent Cairenes who were displaced by a rockslide and moved to this distant development by the government. They complain that they are isolated, and that it costs them nearly as much to take the bus into the city as they can earn in a day’s work.

“We’re in the middle of nowhere. We can’t work or live,” complained Saber Abdel Hady, 31, who relocated three months ago to a 400-square-foot apartment in Haram City with his pregnant wife and two children. They used to inhabit a spacious but illegal dwelling in Cairo’s Manshiet Nasser neighborhood.

He slaughters chickens for $6 a day, but commuting consumes half his wages, so he has stopped going. For now, he’s living on borrowed money, and recently broke into a larger, uninhabited apartment where he plans to squat with his family.

Haram City was conceived as an affordable neighborhood for lower-middle-class professionals, but the government has bought hundreds of units and is filling them with some of Cairo’s poorest inhabitants — importing the city’s historic class tensions to the replacement 6 October City.

Piecemeal development has created short-term hiccups as well. The new development lacks a subway, sufficient jobs, schools and medical services. Businesses, however, are relocating to the new city and the government plans to put many of its ministries and service buildings there.

Greater Cairo needs 2 million new housing units within the next 10 years, said Omar Elhitamy, managing director of Orascom Housing Communities, Haram City’s developer. That demand can be met only if private companies like Orascom create a sizable volume of new homes at low cost, he added.

“It’s not charity, it’s a longer-term vision,” Mr. Elhitamy said. “The project has to provide quality of life.”

He envisions 6 October City’s sprawl eventually meeting Cairo’s western edge, “like Dallas-Ft. Worth or the Twin Cities.”

A few miles farther out in the desert is the extreme side of replacement Cairo: an exclusive golf course community called Allegria, already half built, and the planned luxury development of Westown, flanking the main highway from Cairo to Alexandria. Developers are building a replica of downtown Beirut, which will serve as an urban hub for all the gated communities and other developments proliferating in the desert.

Well-off Egyptians who have moved to the desert cities rave about their new suburban lifestyles.

“Cairo is hot and packed,” said Noha Refaat Elfiky, 33, a market researcher who moved a year ago to Palm Park from Heliopolis, itself built as a leafy getaway from downtown Cairo in the 19th century, but now swallowed by the city. “There will be nothing lost and much gained as everybody moves out of the city.”

Nevertheless, Ms. Elfiky still spends a night or two a week in her family apartment in Cairo. “Sometimes,” she said, “I miss the smell of pollution.”