Across the US, inspired by the success of Portland’s streetcar and a movement toward downtown revitalization and expanding public transit alternatives, projects enhancing place mobility move forward despite controversy.

Are Streetcars Worth the Investment?

By Coby Joseph Published in The City Fix

The Economist recently argued that streetcars are “a waste of money,” citing their high capital costs and inefficiencies as a means of transport. Others have argued that streetcars can be a catalyst for creating dynamic, vibrant urban environments. Both arguments hold some truth. Along with other forms of light rail – as well as metro and bus rapid transit (BRT) – streetcars can be a high-capacity transport option that improves urban mobility, quality of life, and the environment while providing an alternative to private vehicle use. In many instances, however, other forms of public transport may be more cost-effective investments. Cities should undertake comprehensive evaluations that consider the benefits and costs of each public transport system prior to their implementation.

Ten U.S. cities have streetcar projects in various stages of construction, while five more — San Antonio, Kansas City, Fort Lauderdale, St. Louis and Detroit — have secured funding but not yet broken ground. Still other cities, such as Milwaukee, Minneapolis and Los Angeles, have streetcar plans in various stages of development. — Henry Grabar, Salon

When a streetcar — or other catalyst — creates a compact, dynamic place, other kinds of mobility become possible. The densest concentrations of bike-share and car-share stations in Portland are located in the area served by the streetcar. That’s no coincidence. You can literally get anywhere without a car. — Rob Steuteville, Better! Cities and Towns

STORY: A Los Angeles Rail~Volution: A City in Sustainable Transition

Streetcars as a placemaking tool

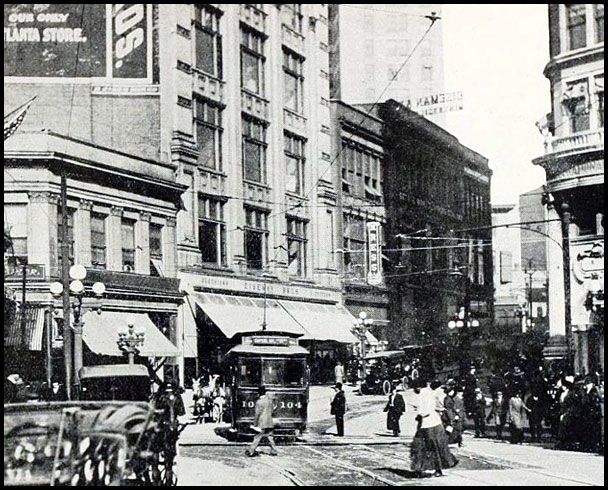

Streetcars have become increasingly common in the United States, with 23 existing systems and another 12 currently under construction. Though they typically travel more slowly and cover shorter distances than other forms of public transport, streetcars can help shape the identity of urban corridors and foster transit-oriented development (TOD). The Portland Streetcar, for example, only travels about six and a half miles per hour, yet it was able to trigger $2.3 billion [others say $4 billion] in private investment due to the increased value of land with streetcar accessibility.

Inside, the ride is smoother and more pleasant; outside, the streetcar is quieter and cleaner than the grunting diesel buses that commonly trawl the streets of American cities. Streetcars attract more riders than equivalent bus routes, offer greater passenger capacity per square foot and can be as long as 150 feet. All this means that fewer drivers and less road space are required to transport the same number of people. Lastly, operating costs are actually lower than on a comparable bus route. — Henry Grabar

Proponents of streetcars argue that they are more appealing than comparable bus services, and are thus better able to attract new riders and tourists. Some cities may not focus on integrating streetcars with the rest of the transport system, and will instead use streetcars as a place-making tool for specific corridors. Europe’s streetcars, typically called trams, differ from their North American counterparts. These trams typically travel longer distances and are isolated from road traffic, making trips faster than those in the United States.

But it’s hard to argue with the success of many streetcar lines in revitalizing American downtowns. A few decades ago, Portland’s urban core had seen little new investment and was suffering from rising vacancies. Its streetcar system now brings some 50,000 passengers daily, catalyzing $4 billion-plus investment and up to 10,000 housing units in the Pearl District and other neighborhoods close to downtown. Downtown Portland enjoys a reputation as a highly livable, walkable, and shoppable area. — Daphne Howland

The streetcar, the thought goes, doesn’t just coax new riders aboard — it draws new residents, developers and visitors into its path. New development means new taxes, which can more than justify the cost of the streetcar, especially if gathered through value capture. — Henry Grabar

STORY: Electric Streetcars: Back to the Urban Future

Bus rapid transit spreading rapidly

Two of the most prominent alternatives to streetcars and light rail projects are bus rapid transit and metro. BRT is a bus-based mode of public transport that operates on exclusive right-of-way lanes. It is a relatively low cost, high-capacity transport option that is spreading rapidly to cities around the world. Originally developed in Latin America in the 1970s, 180 cities now have or are implementing BRT systems, a significant portion of which are in Latin America and Asia. Few high quality BRT systems exist in the United States, where only 360,000 passengers use BRT per day compared to 11,000,000 per day in Brazil. High quality BRT systems feature integrated stations, busways, and information technologies, and can reach relatively high speeds when using express services or fully separated lanes in expressways. BRT capital costs are 4 – 20 times lower than light rail systems, and 10 – 100 times lower than metro systems, with similar capacity and service level.

On transit speeds and urbanism: “By trying to maximize connections to the community, the transit line has to stop more often, slowing speeds. And if built into a legacy urban fabric, this also includes negotiation with tons of cross streets where designers don’t give priority to the transit line. This happens in Cleveland on the Health Line BRT as well as the Orange Line in Los Angeles, even though it has its own very separated right of way. The Gold Line Light Rail in LA and the Orange Line originally had the same distance, yet one was 15 minutes faster end to end. A lot of this had to do with less priority on cross streets given to the Orange Line, not because it was a bus or rail line.” — Jeff Wood, The Overhead Wire

Successful BRT systems can lead to significant economic development and time savings for users. In Istanbul, the typical Metrobüs passenger saves 52 minutes per day, while Mexico City stands to save $141 million in regained economic productivity as a result of travel time reductions from one BRT line. Similar to streetcars, BRT has the potential to generate significant transit-oriented development. For example, Cleveland’s HealthLine BRT generated $5.8 billion in investment, though the project only cost $168.4 million to construct. Unlike electric streetcars, however, BRT systems can be major producers of harmful particulate matter when clean buses and fuels are not used.

STORY: Vision of Sustainable Mobility? High-Speed Rail Challenges California

Metro: A key transport option for large, dynamic cities

Despite requiring huge capital costs, metro systems have the highest capacities and speeds of major public transport options. Metro systems are able to carry more than 30,000 passengers per direction per hour, and can allow business districts in large cities to continue growing, where service by road would be increasingly frustrated by congestion. Metros have relatively high distances between stations, and thus require bus or intermediate public transport services for last-mile connectivity. Currently, 187 cities have a metro system, and this number is set to grow. Metro systems exist in cities throughout the world, with the highest concentration in Europe, Eastern Asia, and the eastern part of the United States. They can be an important piece of sustainable mobility in populous cities, as 16 cities have metro systems with average daily ridership above 2 million passengers.

Cities should consider the benefits and costs of each transport option based on the city’s specific context, budgets and objectives. High quality public transport can be used to reduce road congestion, provide environmental benefits, reduce travel time and costs, shape urban form, and support vulnerable and low-income populations. For each form of public transport discussed, governments should couple investments with zoning changes that increase density and promote mixed-use, transit-oriented development. By investing in the right mix of public transport options, cities can create a culture of sustainable mobility rather than one focused on car use.

Some US Cities with Streetcars Under Development

Below is a brief list of streetcar systems.

Anaheim

Atlanta

Peachtree Corridor Partnership

Baltimore

Charles Street Corridor Trolley

Boise, Idaho

Charlotte

The Charlotte Streetcar Project

Cincinnati

Fort Lauderdale

Forth Worth

Grand Rapids

Interurban Transit Partnership (the Rapid)

But what if the secret of great transit is not which toy you buy, but how you design a network of services to work together?

Thanks for your comment. I think eventual success does rely on system wide investment in multiple modes of transit. But some places have nothing but cars and parking lots and have to start somewhere. What might begin as a toy, say Anaheim’s streetcar, can be a catalyst to supporting and extending other modes like buses, bikes, and walking. And with massive amounts of tourists, conventioneers, and Angel fans, this sort of toy can be an exemplary start. The inclusion of BRT and metros in the discussion is meant to stress your point. Cities need to diversify their modes of mobility.

Pingback: Self-Driving Pod Cars vs. Personal Rapid Transit | WilderUtopia.com