The Kraken myth, a giant squid or legendary massive octopus from the depths of the ocean, known to destroy ships, also has some significant scientific basis for its existence. Here we share an encounter with this magical sea monster in an excerpt from Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Sagas of the Norseland: Behold, the Monstrous, Mysterious Kraken

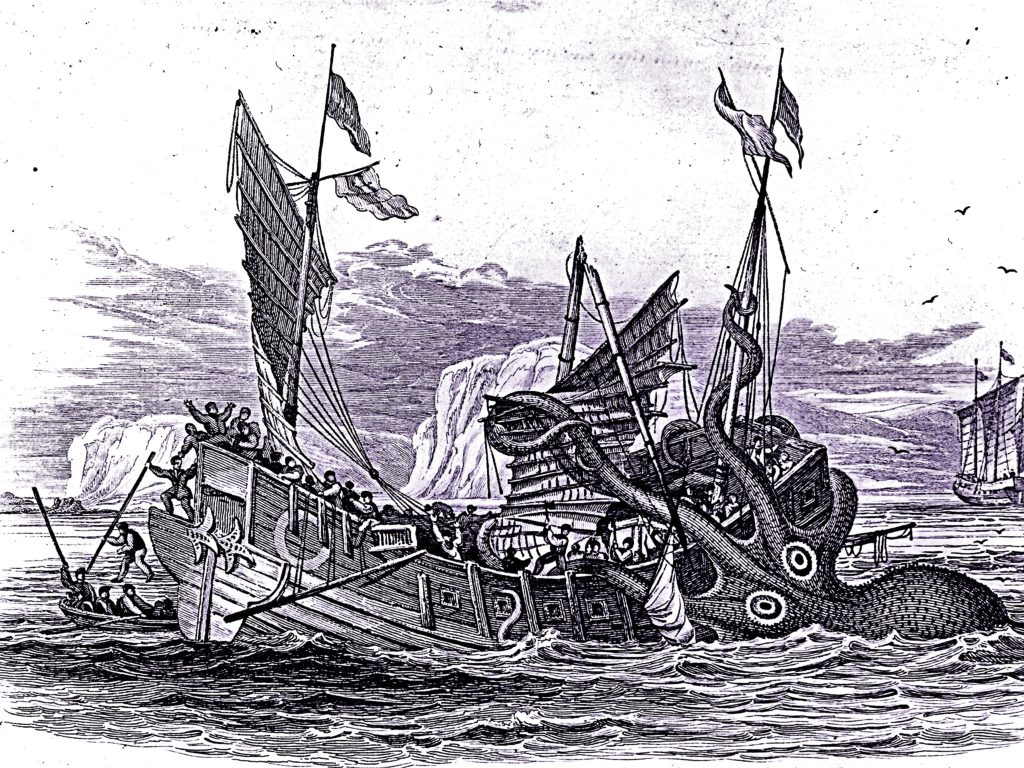

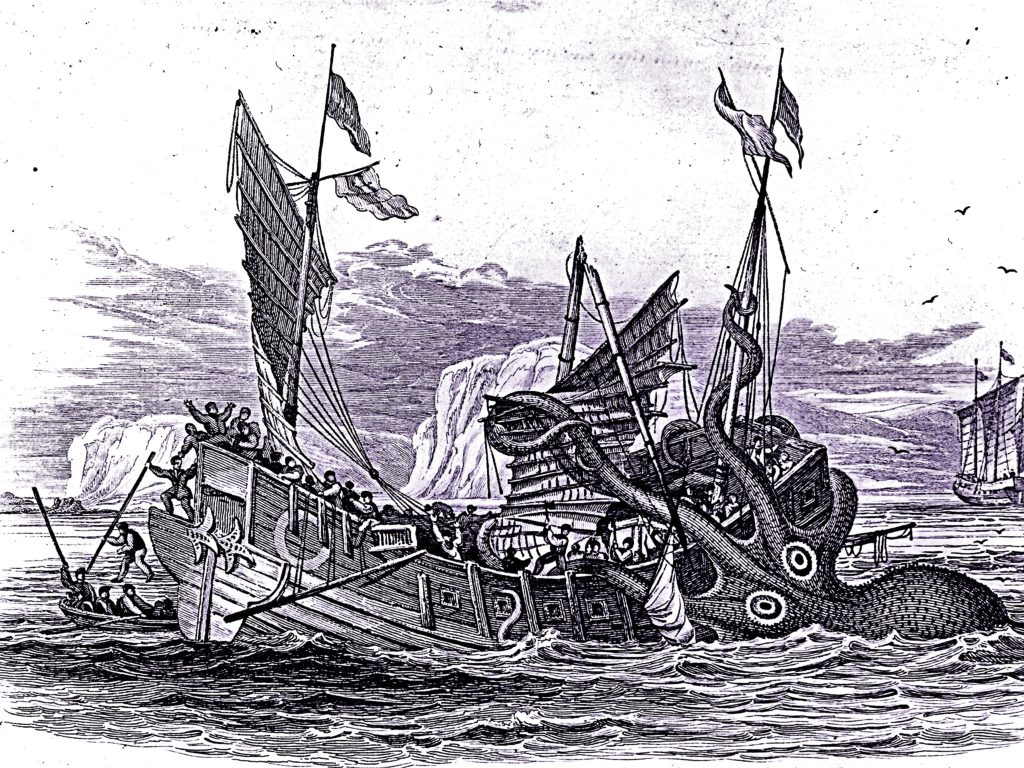

According to the Norse sagas and Scandinavian folklore, the Kraken is a cephalopod-like sea monster of gigantic size. dwelling off the coasts of Norway and Greenland. Today we know the legends of this monster were based on sightings of giant squids.

The first documented evidence of the Kraken’s mesmerizing and destructive power dates back to an obscure manuscript from 1180, according to expert Rodrigo B. Salvador, where it was described by Norway’s King Sverre as a stupendously large monster, big enough to be confused for an island, which prowled the waters surrounding Iceland.

The Kraken was first mentioned in a 13th Century Icelandic saga where Örvar-Oddr and his son encountered two monsters in the sea of Greenland, the Lyngbakr (“heather-back”) and the Hafgufa (“sea-mist”). Around 1250, the anonymous author of the Old Norwegian natural history encyclopedia Konungs skuggsjá described in detail the physical characteristics and feeding behavior of the Hafgufa — or the Kraken.

Further burnishing the case for the reality of the mythical Kraken, a giant cephalopod was found in 1853 stranded on a Danish beach. Norwegian naturalist Japetus Steenstrup recovered the animal’s beak and used it to scientifically describe the giant squid, Architeuthis dux. After 150 years of research into the multi-armed-and-tentacled-behemoth that inhabits all the world’s oceans, there is still much debate as to whether they represent a single species or as many as 20. The largest Architeuthis recorded reaches 18 metres (60 feet) in length, including the very long pair of tentacles.

STORY: Miskitu Stories: ‘Crazy Sickness’ and the Duendes of the Wild

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: A Murderous Kraken

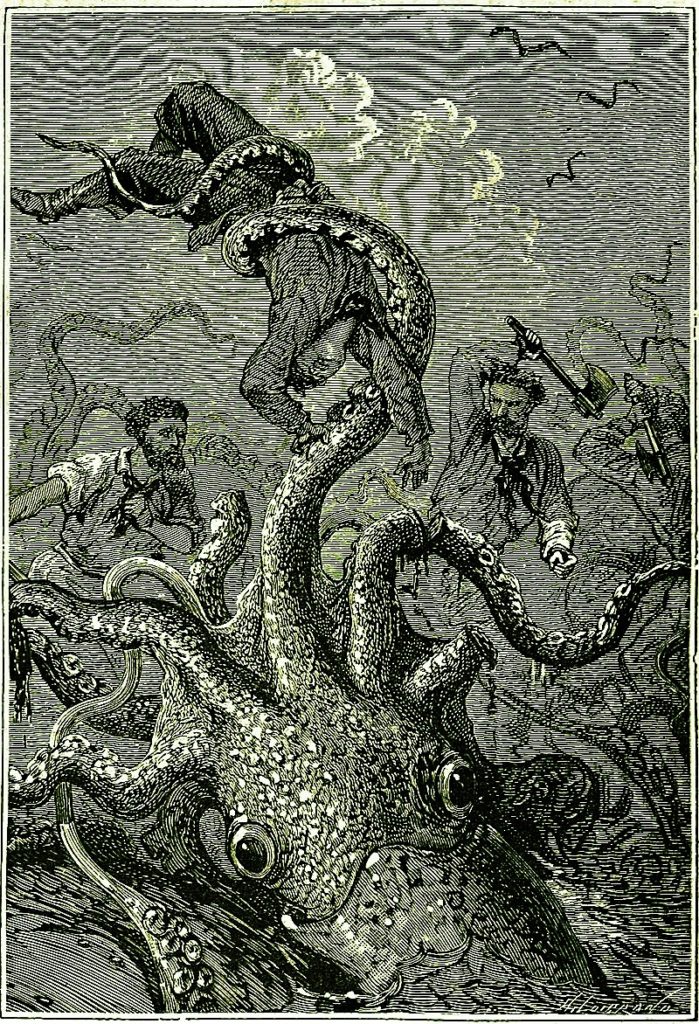

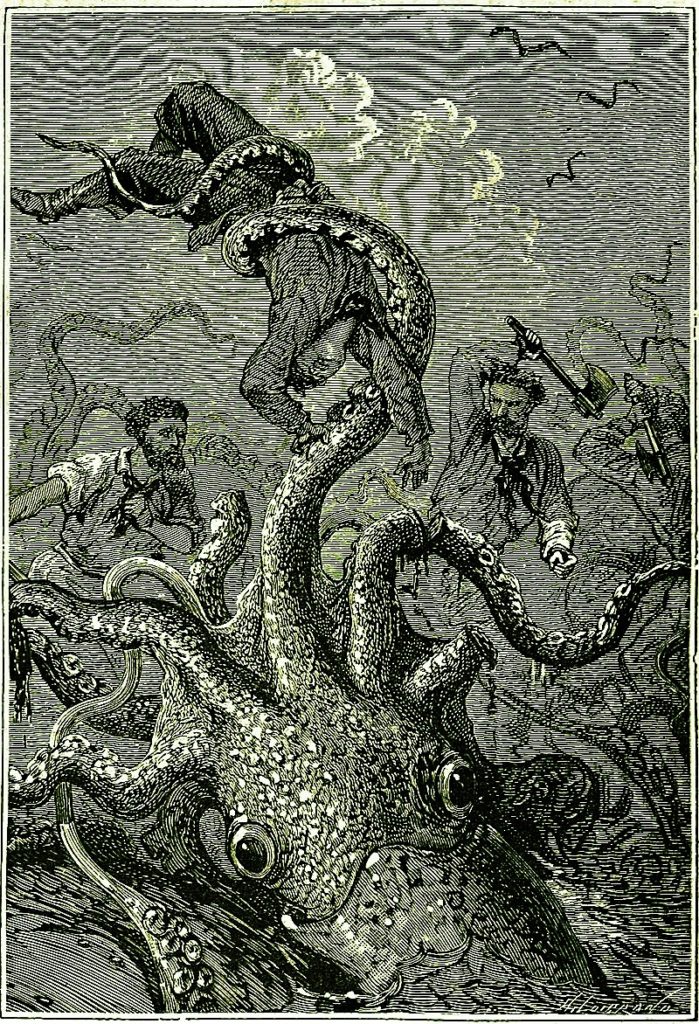

Here is an excerpt from Jules Verne‘s depiction of the famous giant squid in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea from 1870. It was based upon accounts by Eric Pontoppidan, the younger, Bishop of Bergen, from his work, The Natural History of Norway (1752; 1752-1753). Though a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Copenhagen, he is more given to mythology than to science, and Verne brought the myth into literature.

It was about eleven o’clock when Ned Land drew my attention to a fearsome commotion out in this huge seaweed.

“Well,” I said, “these are real devilfish caverns, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see some of those monsters hereabouts.”

“What!” Conseil put in. “Squid, ordinary squid from the class Cephalopoda?”

“No,” I said, “devilfish of large dimensions. But friend Land is no doubt mistaken, because I don’t see a thing.”

“That’s regrettable,” Conseil answered. “I’d like to come face to face with one of those devilfish I’ve heard so much about, which can drag ships down into the depths. Those beasts go by the name of krake—”

“Fake is more like it,” the Canadian replied sarcastically.

“Krakens!” Conseil shot back, finishing his word without wincing at his companion’s witticism.

“Nobody will ever make me believe,” Ned Land said, “that such animals exist.”

Before my eyes there quivered a horrible monster worthy of a place among the most farfetched teratological legends.

It was a squid of colossal dimensions, fully eight meters long. It was traveling backward with tremendous speed in the same direction as the Nautilus. It gazed with enormous, staring eyes that were tinted sea green. Its eight arms (or more accurately, feet) were rooted in its head, which has earned these animals the name cephalopod; its arms stretched a distance twice the length of its body and were writhing like the serpentine hair of the Furies. You could plainly see its 250 suckers, arranged over the inner sides of its tentacles and shaped like semispheric capsules. Sometimes these suckers fastened onto the lounge window by creating vacuums against it. The monster’s mouth—a beak made of horn and shaped like that of a parrot—opened and closed vertically. Its tongue, also of horn substance and armed with several rows of sharp teeth, would flicker out from between these genuine shears. What a freak of nature! A bird’s beak on a mollusk! Its body was spindle-shaped and swollen in the middle, a fleshy mass that must have weighed 20,000 to 25,000 kilograms. Its unstable color would change with tremendous speed as the animal grew irritated, passing successively from bluish gray to reddish brown.

What was irritating this mollusk? No doubt the presence of the Nautilus, even more fearsome than itself, and which it couldn’t grip with its mandibles or the suckers on its arms. And yet what monsters these devilfish are, what vitality our Creator has given them, what vigor in their movements, thanks to their owning a triple heart!

Sheer chance had placed us in the presence of this squid, and I didn’t want to lose this opportunity to meticulously study such a cephalopod specimen. I overcame the horror that its appearance inspired in me, picked up a pencil, and began to sketch it.

“Perhaps this is the same as the Alecto’s,” Conseil said.

“Can’t be,” the Canadian replied, “because this one’s complete while the other one lost its tail!”

“That doesn’t necessarily follow,” I said. “The arms and tails of these animals grow back through regeneration, and in seven years the tail on Bouguer’s Squid has surely had time to sprout again.”

“Anyhow,” Ned Land shot back, “if it isn’t this fellow, maybe it’s one of those!”

Indeed, other devilfish had appeared at the starboard window. I counted seven of them. They provided the Nautilus with an escort, and I could hear their beaks gnashing on the sheet-iron hull. We couldn’t have asked for a more devoted following.

I continued sketching. These monsters kept pace in our waters with such precision, they seemed to be standing still, and I could have traced their outlines in miniature on the window. But we were moving at a moderate speed.

All at once the Nautilus stopped. A jolt made it tremble through its entire framework.

“Did we strike bottom?” I asked.

“In any event we’re already clear,” the Canadian replied, “because we’re afloat.”

The Nautilus was certainly afloat, but it was no longer in motion. The blades of its propeller weren’t churning the waves. A minute passed. Followed by his chief officer, Captain Nemo entered the lounge.

I hadn’t seen him for a good while. He looked gloomy to me. Without speaking to us, without even seeing us perhaps, he went to the panel, stared at the devilfish, and said a few words to his chief officer.

The latter went out. Soon the panels closed. The ceiling lit up.

I went over to the captain.

“An unusual assortment of devilfish,” I told him, as carefree as a collector in front of an aquarium.

“Correct, Mr. Naturalist,” he answered me, “and we’re going to fight them at close quarters.”

I gaped at the captain. I thought my hearing had gone bad.

“At close quarters?” I repeated.

“Yes, sir. Our propeller is jammed. I think the horn-covered mandibles of one of these squid are entangled in the blades. That’s why we aren’t moving.”

“And what are you going to do?”

“Rise to the surface and slaughter the vermin.”

“A difficult undertaking.”

“Correct. Our electric bullets are ineffective against such soft flesh, where they don’t meet enough resistance to go off. But we’ll attack the beasts with axes.”

“And harpoons, sir,” the Canadian said, “if you don’t turn down my help.”

“I accept it, Mr. Land.”

“We’ll go with you,” I said. And we followed Captain Nemo, heading to the central companionway.

There some ten men were standing by for the assault, armed with boarding axes. Conseil and I picked up two more axes. Ned Land seized a harpoon.

By then the Nautilus had returned to the surface of the waves. Stationed on the top steps, one of the seamen undid the bolts of the hatch. But he had scarcely unscrewed the nuts when the hatch flew up with tremendous violence, obviously pulled open by the suckers on a devilfish’s arm.

Instantly one of those long arms glided like a snake into the opening, and twenty others were quivering above. With a sweep of the ax, Captain Nemo chopped off this fearsome tentacle, which slid writhing down the steps.

Just as we were crowding each other to reach the platform, two more arms lashed the air, swooped on the seaman stationed in front of Captain Nemo, and carried the fellow away with irresistible violence.

Captain Nemo gave a shout and leaped outside. We rushed after him.

What a scene! Seized by the tentacle and glued to its suckers, the unfortunate man was swinging in the air at the mercy of this enormous appendage. He gasped, he choked, he yelled: “Help! Help!” These words, pronounced in French, left me deeply stunned! So I had a fellow countryman on board, perhaps several! I’ll hear his harrowing plea the rest of my life!

The poor fellow was done for. Who could tear him from such a powerful grip? Even so, Captain Nemo rushed at the devilfish and with a sweep of the ax hewed one more of its arms. His chief officer struggled furiously with other monsters crawling up the Nautilus’s sides. The crew battled with flailing axes. The Canadian, Conseil, and I sank our weapons into these fleshy masses. An intense, musky odor filled the air. It was horrible.

STORY: Labor Taskmaster: The Yule Cat Monster of Iceland

Watch this video on YouTube

“Release the Kraken,” made famous in 2010’s Clash of the Titans, even though the Kraken mythos definitely is not Greek.

Giant Polypi, In Verse

In 1830 Alfred Tennyson published the irregular sonnet The Kraken, which described a massive creature that dwells at the bottom of the sea:

Below the thunders of the upper deep;

Far far beneath in the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth: faintest sunlights flee

About his shadowy sides; above him swell

Huge sponges of millennial growth and height;

And far away into the sickly light,

From many a wondrous grot and secret cell

Unnumber’d and enormous polypi

Winnow with giant arms the slumbering green.

There hath he lain for ages, and will lie

Battening upon huge seaworms in his sleep,

Until the latter fire shall heat the deep;

Then once by man and angels to be seen,

In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die.

Although scientific confirmation illustrates it is not just a legend, the giant squid remains perhaps the most elusive large animal in the world, in a universe made smaller by people and their debilitating machines that scour the Earth. May the Kraken rise, and be released, again.

Updated 23 February 2021

Pingback: 2 – The Lively Sea: Surfing and Embodiment – Below The Surface

Pingback: Ketea - The Terrifying Greek Sea Monsters Of Ancient Mythology

Pingback: Caracati?e pentru bebelu?i - REVISTA BAABEL