In ancient Roman religion, Ceres was a goddess of agriculture, grain crops, fertility and motherly relationships. The following myth (based on a Greek precedent) tells how her daughter Proserpina was abducted by the ruler of the underworld, forced to become his wife, but with Ceres’ help, she watches over the springtime growth of crops and the cycle of life, death, and rebirth or renewal.

Kidnapping: The Myth of Ceres and Proserpina

Excerpted from a retelling by Lilian Stoughton Hyde

I. The Mourning of the Earth-Mother

On the island of Sicily, the beautiful valley of Enna stood high up among the mountains. Seldom did a human being venture there, not even a shepherd climbed so high, but for goats, sheep, and wild swine.

Ceres, the Earth-Mother, one of the wisest of the goddesses, called the Valley of Enna her home. Ceres had brought to humankind the gift of agriculture, discoverer of spelt wheat, the yoking of oxen and ploughing, the sowing, protection and nourishing of the young seed.

One day Proserpina, the daughter of Ceres, who had grown into a beautiful young woman, was wandering the meadows of Enna. Her hair was as yellow as gold, and her cheeks had the delicate pink of an apple blossom. She seemed like a flower among the other flowers of the valley.

Proserpina had been gathering flowers, and spotted one that seemed a strange, new kind of narcissus. It was of gigantic size, and its one flower-stalk held at least a hundred blossoms.

Proserpina had been accompanied by the valley nymphs, but now was alone, entranced by the narcissus. Running forward to pick this strange blossom, its stalk spotted like a snake, she feared it might be poisonous. Still, it was far too beautiful a flower to be left by itself in the meadow, and she therefore tried to pluck it. When she found she could not break the stalk, she made a great effort to pull the whole plant up by the roots.

All at once, the black soil around the plant loosened, and Proserpina heard a rumbling underneath the ground. Then the Earth suddenly opened, a great black cavern appeared, and out from its depths sprang four magnificent black horses, drawing a golden chariot. In the chariot sat Pluto, god of the underworld, with a crown on his head.

Proserpina’s beauty had dazzled the usually gloomy king. He fell in love with her instantly. When Pluto saw her standing by the flower, he kidnapped her and hurled his chariot down into the darkest depths of the underworld, taking Proserpine with him.

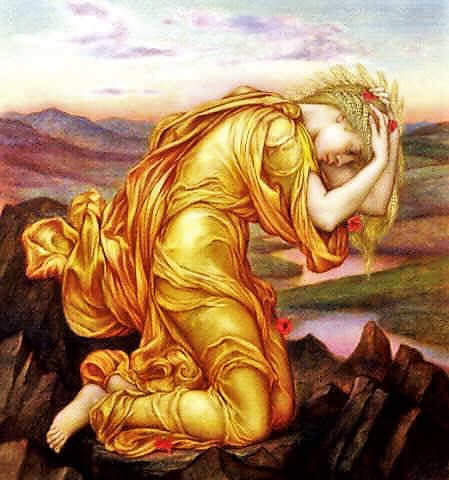

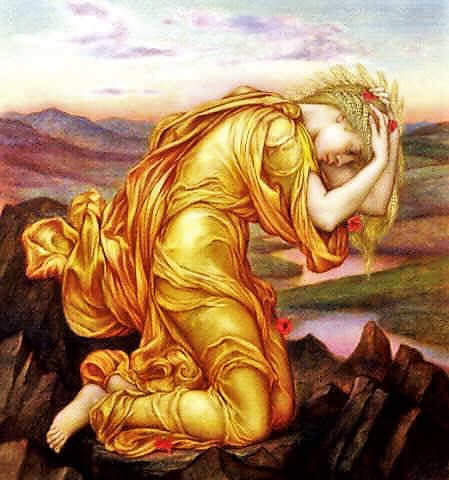

© Musée de Grenoble

Locked in a room in the Underworld, Proserpine cried and cried. She refused to speak to Pluto. And she refused to eat. Legend said if you ate anything in Pluto, you could never leave. She did not know if the legend was true, but did not want to risk it in case someone came to rescue her.

Helios, the sun-god, saw how the underworld god had stolen Proserpina away, and Hecate, goddess of the dark of the moon, who sat near by in her cave, heard the scream and the sound of wheels. No one else had any suspicion of what had happened.

Stygian Proserpine

“I come in purity from a pure people,

Oh Queen of the Dead;

and I claim descent from your blessed race.

But fate and the star-hurled thunderbolt

overwhelmed me, and now I have flown

out of the sorrow heavy wheel.

I move with eager steps

to touch your Crown, and sink into your lap,

My Great Lady; Oh Queen of the Dead.”

“Happy and hlessed you shall be then,

as a God, mortal no more.

You shall be as a young child,

fallen into my own sweet mother’s milk.”

–fragment of a text from Thurii, in southern Italy, approximately 3rd Century BCE, relating to the mysteries of Proserpina

II. Ceres Searches for her Daughter Proserpina

Ceres was far away across the seas in another country, overlooking the gathering in of the harvests. She heard Proserpina’s scream, and like a sea-bird when it hears the distressed cry of its young, came rushing home across the water.

She filled the valley with the sound of her calling, but no one answered to the name of Proserpina. The strange flower had disappeared.

Ceres could learn nothing about her daughter from the nymphs. She sent out her own messenger, the big white crane that brings the rain; but although he could fly very swiftly and very far on his strong wings, he brought back no news of Proserpina.

When it grew dark, the goddess lighted two torches at the flaming summit of Mount Etna, and continued her search. She wandered for nine days and nine nights. On the tenth night, when it was nearly morning, she met a shrouded Hecate, who was carrying a lantern in her hand, as if she, too, were looking for something. Hecate told Ceres how she had heard Proserpina scream, and the sound of wheels, but had seen nothing. Then she flew with the goddess to ask Helios, the sun-god, whether he had not seen what happened that day, for the sun-god travels around the whole world, and must see everything.

Ceres found Helios sitting in his chariot, ready to drive his horses across the sky. He held the fiery creatures in for a moment, and said, “I pity you, Ceres, for I know what it is like to lose a child. But I know the truth. Pluto wanted Proserpina for his wife, so he asked his brother, Jupiter, to give him permission to kidnap her. Jupiter, as her father, gave his consent, and now your daughter reigns over the land of the dead with Pluto.”

Ceres screamed in a rage and thrust her fist toward Jupiter’s citadel on Capitoline Hill in Rome, cursing the god of the sky for aiding in the kidnapping of his own daughter. Then she returned to Earth, disguised as an old woman, and began wandering from town to town.

III. Ceres Arrives at the Palace of Celeus, Disguised as an Old Woman

One day, as she rested near a well in the shade of an olive tree, Ceres watched as the four daughters of Celeus, carrying golden pitchers on their shoulders, came down from their father’s palace to draw water. Remembering her own daughter, she began to weep.

“Where are you from, old woman,” one princess kindly asked.

“I was kidnapped by pirates, and I escaped from being sold as a slave as the ship reached the shore,” said Ceres. “Now I know not where I am.”

“I am old, and a stranger to every one here,” she said, “but I am not too old to work for my bread. I could keep house, or take care of a young child.”

Hearing this, the four sisters ran eagerly back to the palace, and asked permission to bring the strange woman home with them. Their mother told them that they might engage her as nurse for their little brother, Demophoon.

Therefore Ceres became an inmate of the house of Celeus, and the little Demophoon flourished under her care.

Ceres soon learned to love the human baby who was her charge, and wished to make him immortal. She knew only one way of doing this, and that was to bathe him with ambrosia, and then, one night after another, place him in the fire until his mortal parts should be burned away. Every night she did this, without saying a word to any one. Under this treatment Demophoon was growing wonderfully godlike; but one night, his mother being awake very late, and hearing some one moving about, drew the curtains aside a very little, and peeped out. There, before the fire-place, where a great fire was burning, stood the strange nurse, with Demophoon in her arms. The mother watched in silence until she saw Ceres place the child in the fire, then she gave a shriek of alarm.

The shriek broke the spell. “Stupid woman!” shouted Ceres, snatching the baby from the fire. “I was going to make your son a god! He would have lived forever! Now he’ll be a mere mortal and die like the rest of you!”

Ceres took Demophoon from the fire and laid him on the floor. Then, throwing off her blue hood, she suddenly lost her aged appearance, and all at once looked very grand and beautiful. Her hair, which fell down over her shoulders, was yellow, like the ripe grain in the fields. The king and queen then realized that the boy’s nurse was Ceres, the powerful goddess of grain, and they were terrified.

“I will only forgive you,” said Ceres, “if you build a great temple in my honor. Then I will teach your people the secret rites to make the corn grow.”

IV. Ceres Goes on Strike and the World Starves

At dawn the king ordered a great temple be built for the goddess. Yet after it was completed, Ceres did not reveal the secret rites. Instead, she sat by herself all day in a nearby dark cave, grieving for her kidnapped daughter. She was in such deep mourning that everything on Earth stopped growing, with no grain to be ground into flour for bread. It was a terrible year, the trees in the olive orchards dropped their leaves, and even the sheep that fed among the water-springs in the valley of Enna grew so thin that it was pitiful to see them.

Jupiter saw that without Ceres, the Great Mother, there could be no life on the Earth. In time, all living beings would die for lack of food. He therefore told Iris to set up her rainbow-bridge in the sky, and to go quickly down to the dark cave where Ceres mourned for Proserpine, that she might persuade the goddess to forget her sorrow, and return to tending to the drying, dying fields.

Iris found Ceres among the shadows, wrapped in dark blue draperies that made her almost invisible. The coming of Iris lighted up every part of the cave and set beautiful colors dancing everywhere, but it did not make Ceres smile.

After this, Jupiter sent the gods, one after another, down to the cave; but none of them could comfort the Earth-mother, as they pleaded with her to make the Earth fertile again. “I never will,” she said, “not unless my daughter is returned safely to me.”

Jupiter had no choice but to send his son Mercury, the messenger god, down into Pluto’s kingdom, to see whether he could not persuade that grim king to let Proserpine return to her mother. Mercury was known as a great deal-maker, but his uncle, overseer of the underworld, was really in love. This was no passing fancy.

V. The Return of Proserpina to the Light

Wandering in the lower world, Mercury passed through dark smoky cavers filled with ghosts and phantoms, until he came to the misty throne room of Pluto and Proserpina. Though the young woman was still frightened, she had grown accustomed to her new home and had almost forgotten her life on Earth.

“Your brother, Jupiter, has ordered you to return Proserpina to her mother,” Mercury told Pluto. “Otherwise, Ceres will destroy the Earth.”

Proserpina jumped up from her throne, eager to see her mother again, and Pluto, seeing how glad she was, could not withhold his consent. So he ordered the black horses and the golden chariot brought out to take her back; but before she sprang to the chariot’s seat, he spoke softly to her, “If you stay, you’ll be queen of the underworld, and the dead will give you great honors.”

“I would rather return,” she whispered.

Pluto sighed, then said, “All right, go. But before you leave, eat this small seed of the pomegranate fruit. It is the food of the underworld — it will bring you good luck.”

Proserpine tasted the fruit, taking just four seeds. Then the black horses swiftly carried Mercury and herself into the upper world, and straight to the cave where Ceres sat.

When Ceres saw her daughter coming, she ran out of the cave, and Proserpina sprang from the chariot and into her mother’s arms.

Proserpina told her mother everything — how she had found the wonderful narcissus, how the Earth had opened, allowing King Pluto’s horses to spring out, and how the dark king had snatched her and carried her away.

“But, my dear young woman,” Ceres anxiously inquired, “have you eaten anything since you have been in the underworld?”

Proserpina confessed that she had eaten the four pomegranate seeds. At that, Ceres beat her breast in despair. “You have eaten the sacred food of the underworld,” she said to Proserpina. “Now you must return for four months of every year — one for each pomegranate seed — in the underworld with Pluto, your husband.”

And this is how the seasons began — in autumn Ceres changes the leaves to shades of brown and orange (her favorite colors) as a gift to Proserpina before she has to return to the underworld. When winter comes, the Earth grows cold and barren because Proserpina lives in the underworld with Pluto, and her mother hides in a cave, mourning. Yet when her daughter returns to her, Ceres, goddess of grain, turns the world to spring and summer.

All nature must sleep for those four barren and cold months. But the people had no fear now, for they knew that Proserpina would surely come back, and that the great Earth-mother would then care for her children again.

The cult of Ceres and Proserpina was among the most celebrated in ancient times in Sicily. The English word “cult” comes from the Latin cultus, which simply means “cultivate” and referred to cultivating relationships with the Gods through offerings and prayers. The Ceralia, or the festival of Ceres, was celebrated anciently in April with a public procession, led by torch bearing priests, to the temple of Ceres. In The Golden Ass by Apulieus, Proserpina is referred to as being the Goddess of the Sicilians. In modem times, the story of Proserpina is known as a “Sicilian folktale” throughout Italy.

This version of the story of Ceres and Proserpina, edited by Jack Eidt, was featured in the book entitled Favorite Greek Myths by Lilian Stoughton Hyde, published in 1904 by D. C. Heath and Company. A book of the same name included retellings by Mary Pope Osborne, published by Scholastic in 1989.

Pingback: Question Patriarchy: How the Devil Married Three Sisters | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Mosaic Masterpiece at Monreale Cathedral in Sicily - WilderUtopia