In Aztec (also called Mexica) cosmology, the soul’s journey to the Underworld after death leaves them with four destinations: the Sacred Orchard of the Gods, the Place of Darkness, the Kingdom of the Sun, and a paradise called the Mansion of the Moon. The most common deaths end up on their way to Mictlán (Place of Darkness) with its nine levels, crashing mountains and rushing rivers, and four years of struggle. This pantheon of gods and goddesses and the expanse of the 13 Heavens provides the cultural basis for the Day of the Dead customs and celebrations.

Journey Through the Underworld

Based on a post by Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, Published by Zoe Saadia at Pre-Columbian Americas

The following is provided as a lesson at a fictional school for noble boys and girls, but presents the cosmology quite comprehensively, where the manner of one’s death determines their Land of the Dead destination.

Today I will talk of the Four Mansions of the Dead. In particular the journey we have to do while reaching Mictlán.

But, before that, you need to know that Mictlantecuhtli, the skeletal Lord of the Land of the Dead is the supreme ruler of Mictlán. He oversees the place of eternal smoke and darkness, along with his consort Mictlancihuatl.

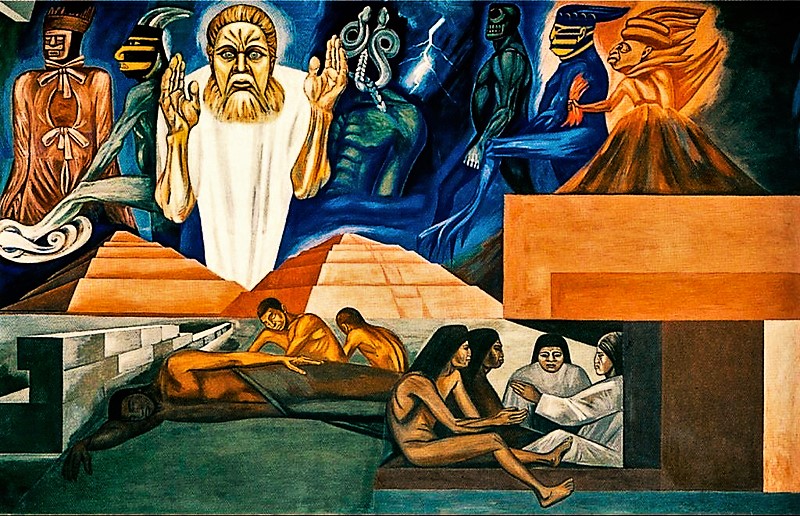

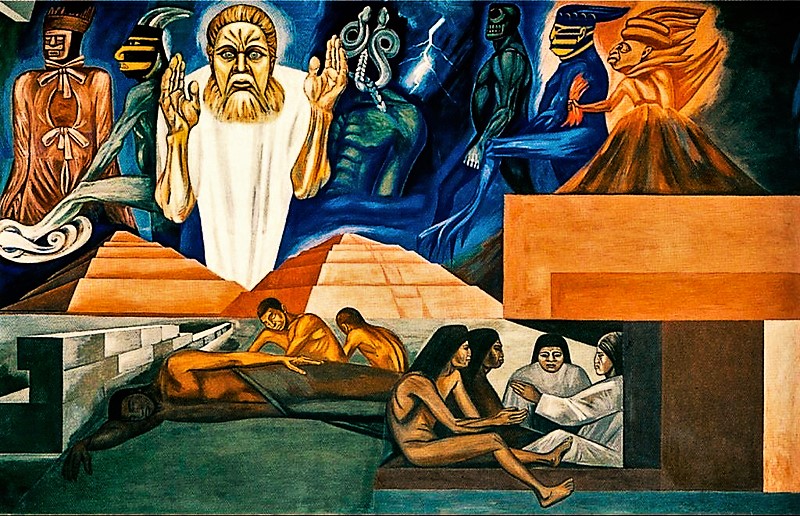

Mictlán is the underworld of the Nahua People (also known as the Aztec), ruled over by its Lord and Lady. It is a gloomy place, reached by the dead only after wandering for four years beneath the Earth, accompanied by a “soul-companion,” a dog which was customarily cremated with the corpse. Aztec myth tells how the deity Quetzalcoatl, who in the Nahuatl language means “feathered serpent,” journeyed to Mictlán at the dawning of the Fifth Sun (the present world era), in order to restore humankind to life from the bones of those who had lived in previous eras. For bones are like seeds: everything that dies goes into the Earth, and from it new life is born in the sacred cycle of existence. — Quetzalcoatl’s Descent To Mictlán

At sunset, Mictlantechutli, along with Tonatiuh, take their place upon the sun, to illuminate the world of the dead.

Tonatiuh, the Star God, becomes Tzontemoc at dusk to light the world of Mictlantecuhtli at night.

The legend says that, after Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca created the world, the day and night, they placed Mictalntecuhtli and his wife Mictlancihuatl as Lord and Lady of the underworld.

The counterpart of Mictlán is the paradise known as Tlalocán, the home of the god Tlaloc, where the people dead from drowning or lightning would arrive.

So, as I said, there were four mansions of the dead:

- Chichihuacuauhco

- Mictlán

- Ilhuuicatl-Tonatiuh

- and Tlalocán.

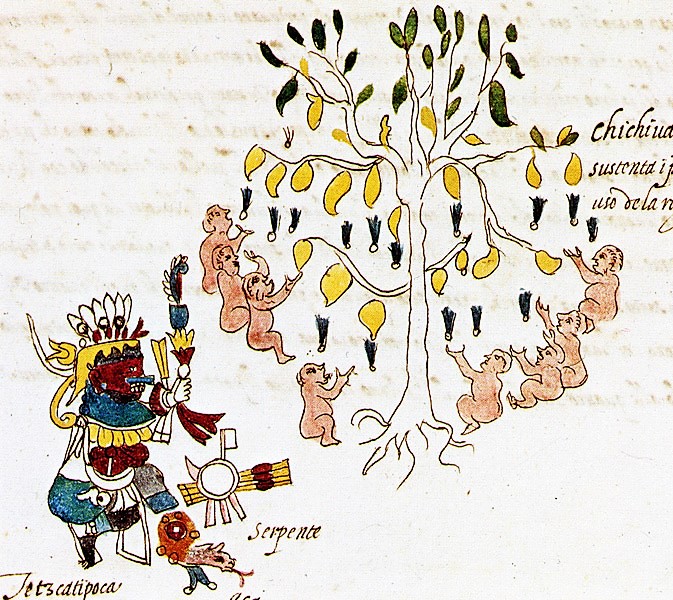

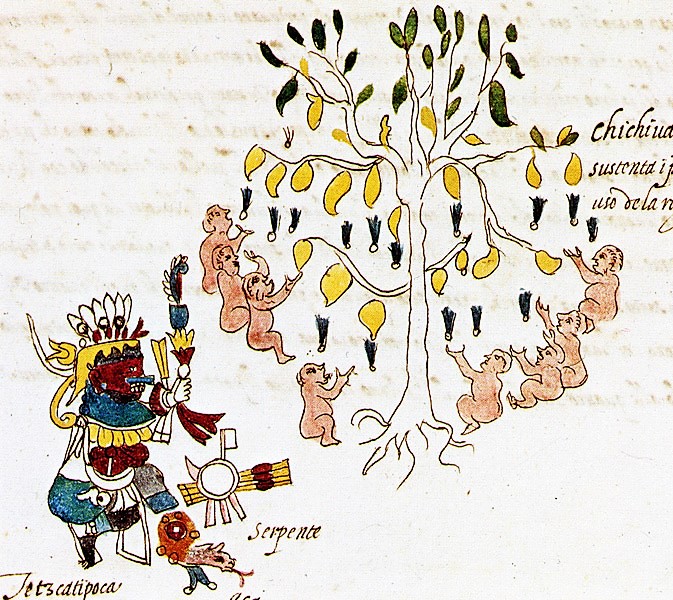

The Chichihuacuauhco was the first mansion.

This was the place of the dead children. In its middle there was a large tree, whose branches dripped milk, so the children could feed and gain strength.

These children would return to the world when the race that is inhabiting the Earth, our world of the Fifth Sun, will be destroyed. That is why their death was necessary, because they were chosen to populate the Earth in the future, when no one will be left alive.

It was believed that these children reincarnated after their death in this mansion, where they lived physically until they were called by the gods.

Then Mictlán was the second mansion.

People who eventually succumbed to illness and old age went to Mictlán. In order to reach it, the soul has to make a four year journey, passing through nine layers of the Underworld and various daunting tests.

First, the dead would come to a place where a great river called Apanohuaya (where one crosses the river) roared along, wide and gushing, intimidating and impossible to swim across.

To cross it one needed the help of an Itzcuintli (xoloitzcuintle), a special dog each family raised and cremated alongside the mourned deceased.

STORY: Day of the Dead: Aztec Dance Honoring the Soul’s Rest

Among the Aztecs, the god Xolotl was a monstrous dog. During the creation of the Fifth Sun, Xolotl was hunted by Death and escaped him by transforming himself first into a sprout of maize, then into maguey leaves and finally as a salamander in a pool of water. The third time that Death found Xolotl, he trapped and killed him. Three important foodstuffs were produced from the body of this mythological dog. Mictlantecuhtli, Lord of the Dead, had the bones of man in the underworld, kept over from the previous creations. Xolotl descended to the underworld to steal these bones so that man could be reborn in the new creation of the Fifth Sun. Xolotl managed to recover the bones and brought man to life by piercing his penis and bleeding upon them. Xolotl was seen as an incarnation of the planet Venus as the Evening Star (the Morning Star was his twin brother Quetzalcoatl). Xolotl was the canine companion of the Sun, following its path through both the sky and the underworld. Xolotl’s strong connection with the underworld, death and the dead is demonstrated by the symbols he bore. In the Codex Borbonicus Xolotl is pictured with a knife in his mouth, a symbol of death, and has black wavy hair like the hair worn by the gods of death. [From Read & Gonzalez 2000, Fernández 1992, and Neumann 1975]

Upon recognizing his dead master, the dog would bark, then rush to help the deceased to cross the river, carrying its master upon his back while swimming.

The Journey to Mictlán was brutal.

After the crossing the great river, the deceased was stripped of all his clothes, beginning the second part of his journey between two mountains that conflicted with each other. This pass was called Tepetl Monamiclia, and the deceased would make his way warily, haunted by the fear that the two mountains would clash, crushing the passing traveler.

At the end of the pass, the deceased would be forced to walk down the hill strewn with flints and sharp obsidian, made of the same material as our knives, called Ilztepetl. The stones would cut the dead them as they passed, merciless and relentless.

The next stage was the walk through Celhuecayan, eight mountains, covered with perpetual snow that would fall on and on, whipped by strong winds. It was said that the winds in these moors were so cold and strong it would cut the body as obsidian blades.

After this the dead would arrive at the foot of the hill, the last stop in the first part of the journey called Paniecatacoyan. These moors were cold and large, where the dead would have to walk endlessly, crossing the desolated land.

Done with the first test, the dead would take a long path, where they would be struck with arrows. This place was called Temiminaloyan and the arrows were fired by unseen hands, trying to harm the passersby.

At the end of the path, they would arrive at the place inhabited by thousands of fierce beasts. When any of the beasts reached them, the passersby would have to throw open their chests and let the beasts eat their hearts, Tecoylenaloyan.

Afterwards, they would be force to dive into the Apanuiayo, where the water was black, and where the lizard called Xochilonal had lived. The dead would have to swim in this lake, dodging the animals, including the terrifying lizard to get to the next test.

Next, they would have to wade through nine rivers, on a path of mist and dark, called Izmictlan Apochcalolca. The sun never rose in this place.

Finally, tired, injured and exhausted with suffering, they would reach their final destination on Chicunamictlan, where they would meet Mictlantecuchtli, the fierce God of the Death, who would receive them with vengeance.

Here the cycle would end forever and here they would live until their bodies and their lives would extinguish.

The long journey lasted for four years, in which the deceased came to his eternal rest.

This was the mansion to which came most of the dead, people who would die of natural causes.

The third mansion was the Kingdom of the Sun.

Here the warriors, slaughtered at the hands of their enemies, would rest. Also included were the souls of those women who died in childbirth. Among the Aztecs, the pregnant woman was like a warrior who symbolically captured her child for the Aztec state in the painful and bloody battle of birth. Considered as female aspects of defeated heroic warriors, women dying in childbirth became fierce goddesses who carried the setting sun into the netherworld realm of Mictlán.

This place was outside the time, a wonderful infinite place, a beautiful plain, and every time the sun would come up, they would hear the sound of the warriors beating their shields.

After four years, these warriors would turn into rich bird-feathers, small, living creatures eating the flowers.

The iconography of Tonatiuh’s attire provides a visual explanation for what his role as the sun god entailed. The deity is usually depicted with arrows and a shield to show that he is a warrior. Tonatiuh often carries a maguey spine in one hand to signify that he takes part in bloodletting practices as a means of sacrifice. The importance of sacrifice is also reinforced by depictions of balls of eagle feather or the eagle itself, which were markers of sacrifice. Tonatiuh’s connection to the sun leads us to believe that the eagle is a reference to the ascending and descending eagle talons, which is a visual metaphor for capturing the heart or life force of a person. [From Townsend, Richard (1979). ‘State and Cosmos in the Art of Tenochtitlan’. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks].

Upon the Earth, in our world of the Fifth Sun, these birds were treated with honor, because we knew they were the souls of the warriors who had died in a battle. These birds are hummingbirds. Some would also become butterflies.

The fourth mansion was what Catholics took for a paradise.

Those who had died by drowning, lightning, and other deaths related to water and rain would arrive at Tlalocán, the Mansion of the Moon, a place of unending springtime and a paradise of green plants. This place belonged to Tlaloc (Nahuatl: “He Who Makes Things Sprout”).

Tlaloc is also associated with caves, springs, and mountains, most specifically the sacred mountain in which he was believed to reside. His animal forms include herons and water-dwelling creatures such as amphibians, snails, and possibly sea creatures, particularly shellfish. The Mexican marigold, Tagetes lucida, known to the Aztecs as yauhtli, was another important symbol of the god, and was burned as a ritual incense in native religious ceremonies. [From Sahagún, Fray Bernardino de (1569). ‘Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain’]

The dead arriving here would live happy, fresh and unconcerned. These dead were not cremated, but buried, interred with a piece of wood which was believed to sprout leaves and flowers once the person had entered Tlalocán. Here people enjoyed food and fruits in abundance, a luxury deserving the realm of the supreme god of rain and agriculture.

And so, between those mansions the dead Mexica were divided, each person going to his designated place in the Mexican Underworld.

There were other pseudo-mansions to which people arrived if killed in special situations. For example, noble women dead in childbirth were going to Cihuateteo.

Mictlán was located below our world.

The Ilhuuicatl-Tonatiuh was upon the sun itself.

Tlalocán on the moon.

The Chichihuacuahco location was unknown, but it said it was out of this world.

And those were the mansions of the dead, and the journey that the dead suffered when they were in Mictlán.

And so today ends the night of #LeyendasMexicas.

Bibliography

López Austin, Alfredo. The Human Body and Ideology: Concepts of the Ancient Nahuas. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1980.

Furst, Jill Leslie McKeever. The Natural History of the Soul in Ancient Mexico. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995.

Neumann, Franke J. (1975). “The Dragon and the Dog: Two Symbols of Time in Nahuatl Religion”. Numen, Vol. 22, Fasc. 1 Apr 1975. Brill Publishers: 1–23.

Sahagún, Fray Bernardino de. Primeros Memoriales, translated by Thelma Sullivan. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

Sahagún, Fray Bernardino de. Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, translated by Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble. 13 vols. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research, 1950–1982.

Townsend, Richard. ‘State and Cosmos in the Art of Tenochtitlan’. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, (1979).

Aztec Religion, from Death and Dying

Historia En El Calmecac, from Zoe Saadia

Mictlan, Wikipedia

Quetzalcoatl, WilderUtopia

Xolotl, from Ancient Origins

Updated 23 October 2023

Pingback: Day of the Dead: Aztec Dance Honoring the Soul's Rest | WilderUtopia.com

I am interested in the image of (Mictlantechutli ) you have here. What role does this God play out during the last days, judgement day, doomsday? Also please email me if you have a moment to spare.

I am comparing what I have found to known ancient gods relating to underworld, serpents, and judgement related information.

This looks and could be a possible, but need the information which will confirm.

Thank you

Bart

Pingback: Dia de los Muertos – Ryan Gonzalez, English 102

Pingback: Aztec Myth: Quetzalcoatl Journey to Land the Dead - WilderUtopia

Mictlantecuhtli Card Game hero; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qG6CrkLhhbw