We have come to believe the Easter Bunny lays eggs on a day set for celebration of the resurrection of Christ. What are its pagan origins as a ritual associated with spring equinox?

The Rites of Spring

By Dr. Leo Ruickbie, Director of WICA.

The end of March is the focus for a number of religious and traditional celebrations. As the sun appears to cross the earth’s equator on the 20th or 21st of March, entering the Zodiacal sign of Aries, day and night become equal in length. This astronomical phenomenon is a day anciently revered amongst Pagan peoples. Their festivals included Alban Elfed (Autumn Equinox), the Teutonic festival in honor of Eostre, Roman Hilaria Matris Deûm, Welsh Gwyl Canol Gwenwynol (“Day of the Gorse”), the Wiccan Eostar (Ostara) Sabbat and the Christian Feast of the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary (Lady Day), as well as Easter itself.

Eostre – the Germanic goddess of dawn and fertility, whose name gives us the word Easter – must be pleased. Two millennia of Christianity, and she has yet to be displaced from our annual celebration of fecundity. Easter egg hunts nod to both pagan and Christian traditions. Eggs, naturally, represent birth and they remain a central part of Christian Easter celebrations in most European countries. – Justine Hankins, The Guardian UK

Origins and History of Ostara

Today, Ostara is one of the eight major holidays, sabbats or festivals of Wicca. It is celebrated on the Spring Equinox, which in the northern hemisphere is around the 20th or 21st of March and in the southern hemisphere around the 23rd of September. Its modern revival is linked to some of the oldest traditions of mankind.

The Month of the Goddess

The name is thought to be derived from a goddess of German legend, according to Jacob Grimm in his Deutsche Mythologie. A similar goddess named Eostre was described by the Venerable Bede. Bede indicated that this name was used in English when the Paschal (Passover) holiday was introduced. Since then this name (not the holiday) has been converted to Easter, or in German Ostern. Some scholars question both Bede’s and Grimm’s conclusions due to a lack of supporting evidence for this goddess. Others argue that a lack of further documentation is not surprising given that Bede is credited with writing the first substantial history of England (in which he described Eostre as a goddess whose worship had already passed) and Grimm was specifically attempting to capture oral traditions before they might be lost.

Despite these reservations, the idea of Eostre has become firmly established in many minds. Without any consideration of these problems, the folklorist Dr Jonathan Young categorically states:

Easter has deep roots in the mythic past. Long before it was imported into the Christian tradition, the Spring festival honored the goddess Eostre or Eastre.

According to Bede and Einhard in his Life of Charlemagne, the month called Eostremonat (Ostaramanoth) was equated with April. This would put the start of “Ostara’s Month” after the Equinox in March. It must be taken into account that these “translations” of calendar months were approximate as the old forms were predominantly lunar months while the new were based on a solar year. Thus start of Eostremonat would actually have fallen in late March and could thus still be associated with the Spring Equinox.

The holiday is a celebration of spring and growth, the renewal of life that appears on the earth after the winter. In mythology it is often characterized by the rejoining of the goddess and her lover-brother-son, who spent the winter months in death. This is an interesting parallel to the biblical story in which Jesus is resurrected (the reason Christians celebrate Easter), pointing to another appropriation of pre-Christian religious figures, symbols and myths by early Christianity.

Word Origins. Etymologically, Eostre, or, as it is sometimes called, Ostara, may come from the word “east,” meaning dawn. Others have also tried to link Eostre with “estrogen” and “estrus.” These words, however, are more widely considered to be derived from the Greek oistros, meaning “gadfly” or “frenzy.” Interestingly, the word “spring” (from to spring, to leap or jump up, burst out, 0ld English springan, a common Teutonic word, compare to the German springen), primarily the act of springing or leaping, is applied to the season of the year in which plant life begins to bud and shoot.

The Antiquity of Ostara. Ostara is a modern Wiccan festival and there is no evidence that Spring Equinox festivals were called by this name in the past. However, there is no direct proof of many Christian or pagan traditions, so a lack of evidence should not necessarily be taken as disproof.

Wiccan Interpretations

The Cycle of Birth, Death and Rebirth

Goddess of fertility and new beginnings, we take this opportunity to embrace Eostre’s passion for new life and let our own lives take the new direction we have wanted for so long. (Goddess.com.au)

Many Wiccans situate Eostre (Ostara) within a symbolic cycle of birth, death and rebirth. As the quotation above demonstrates, the particular role of Eostre is internalized and turned into a self-empowering meditation. Again Dr. Young re-inforces this, by no means definitive, interpretation: “The annual event in honour of Eastre celebrated new life and renewal.”

However, other views also add a darker element, according to Mike Nichols: “The god of light now wins a victory over his twin, the god of darkness.”

Nichols has attempted a reconstruction of the symbolic events of this time of year using the Welth mych-cycle of the Mabinogion. By this interpretation the Spring Equinox is the day on which the reborn Llew exacts his revenge on Goronwy by piercing him with the spear of sunlight. Reborn or returned to health at the Winter Solstice, Llew is now able to challenge and defeat his rival twin and mate with his lover/mother. Meanwhile the “Great Mother Goddess, miraculously returned to virginity at Candlemas, now receives the sun god’s advances and conceives a child. This child will be born at the next Winter Solstice, nine months from now, at once closing the cycle and re-opening it.

STORY: The Pagan Spring Fertility Origins of May Day

Christianity and Easter

Contrary to what the Church may tell you, Christianity came late to the Easter party. There is no indication of the observance of the Easter festival in the New Testament, or in the writings of the apostolic Fathers. A comment made by St. Chrysostom on I Cor. V. 7 has been supposed to refer to an apostolic observance of Easter, but this is erroneous. The sanctity of special times was an idea absent from the minds of the first Christians. The ecclesiastical historian Socrates (Hist. Eccl. V. 22) states that neither Jesus nor his followers enjoined the keeping of this or any other festival. He attributes the observance of Easter by the Church to the perpetuation of an old tradition, just as many other customs have been established.

Easter Bunny Pagan Origins, Superstitions and Traditions

Elements of old beliefs linger in current “superstitions.” According to these, it is said that something new should be worn at Easter to bring good luck. Easter Parades reflect this idea about wearing new clothes.

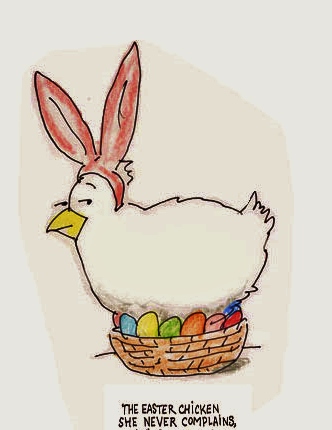

It was the Germans who came up with the odd idea of an egg-laying hare or rabbit that left gifts for children who had gone to the trouble of leaving their caps or bonnets out for rabbits to nest in. This quaint custom arrived in the US along with German migrants.

Eggs and Rabbits. The Easter Bunny is German in origin. He first appears in literature in 16th century as a deliverer of eggs. All rabbits and hares were thought to lay eggs on Easter Day, but the Easter Bunny specifically sought out and rewarded well-behaved children with colored eggs in a manner reminiscent of Yule customs. The movements of the hare, leaping and zig-zagging across the fields, were thought to hold clues to the coming year.

Eggs themselves are obvious symbols of resurrection and continuing life, as well as fertility. Early humans thought the return of the sun from winter darkness was an annual miracle, and saw the egg as a natural wonder and proof of the renewal of life. As Christianity spread the egg was adopted as a symbol of Jesus’s alleged resurrection from the tomb. According to Young, the Easter Bunny is:

a continuation of the reverence shown during the spring rites to the rabbit as a symbol of abundance. The honoring of such emblems of fertility extended to eggs. The egg serves as a representation of new life. It stands for the renewing power of nature and, by extension, agriculture. The egg can also symbolize regeneration in a spiritual or psychological sense. The ritual of coloring Easter eggs stems from the tradition of painting eggs in bright colors to represent the sunlight of spring.

Young goes on to suggest that: “This might also be a good time to find the inner Easter Bunny.”

Brief Bibliography

- Bede, De Temp. Rat. c. xv.

- St Chrysostom, Commentary on I Cor. V. 7.

- Einhard, Life of Charlemagne, trans Samuel Epes Turner. Harper and Brothers, 1880.

- Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911.

- Goddess.com.au, accessed 9th February, 2006.

- Grimm, Jakob, Deutsche Mythologie. 1835.

- Nichols, Mike, ‘Lady Day: The Vernal Equinox’, 1999.

- Socrates, Hist. Eccl. V. 22.

- Young, Jonathan, ‘Symbolism of Spring’, Vision Magazine, April 2003.

Updated 22 March 2021

Thanks regarding providing these types of good

posting.

Pingback: The Pagan Spring Fertility Origins of May Day