The story of a Pilgrim Thanksgiving was a fairy tale told by Lincoln to unite the Union. The Wampanoag version of the harvest festival with the English settlers is a day of mourning for a land taken away, a culture subverted and a people disappeared from epidemic and massacre.

What Really Happened at the First Thanksgiving? The Wampanoag Side of the Tale

By Gale Courey Toensing, Published in Indian Country Today Media Network

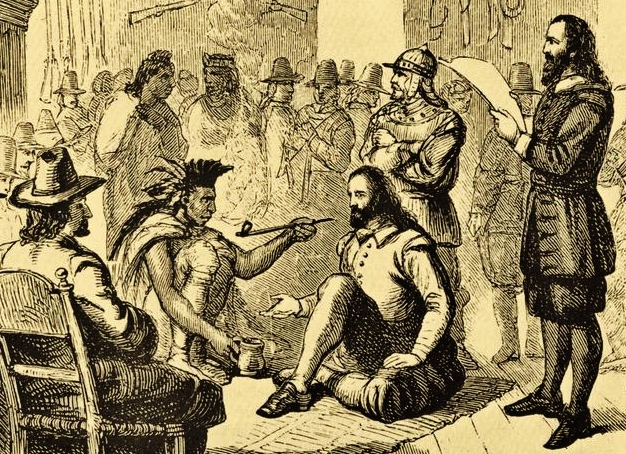

When you hear about the Pilgrims and “the Indians” harmoniously sharing the “First Thanksgiving” meal in 1621, the Indians referred to so generically are the ancestors of the contemporary members of the Wampanoag Nation. As the story commonly goes, the Pilgrims who sailed from England on the Mayflower and landed at what became Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1620 had a good harvest the next year. So Plymouth Gov. William Bradford organized a feast to celebrate the harvest and invited a group of “Native American allies, including the Wampanoag chief Massasoit” to the party.

Watch this video on YouTube

The feast lasted three days and, according to chronicler Edward Winslow, Bradford send four men on a “fowling mission” to prepare for the feast and the Wampanoag guests brought five deer to the party. And ever since then, the story goes, people in the US have celebrated Thanksgiving on the fourth Thursday of November. Not exactly, Ramona Peters, the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe’s Tribal Historic Preservation Officer told Indian Country Today Media Network in a conversation on the day before Thanksgiving 2012—391 years since that mythological “First Thanksgiving.”

We know what we’re taught in mainstream media and in schools is made up. What’s the Wampanoag version of what happened?

Yeah, it was made up. It was Abraham Lincoln who used the theme of Pilgrims and Indians eating happily together. He was trying to calm things down during the Civil War when people were divided. It was like a nice unity story.

So it was a political thing?

Yes, it was public relations. It’s kind of genius, in a way, to get people to sit down and eat dinner together. Families were divided during the Civil War.

So what really happened?

We made a treaty. The leader of our nation at the time—Yellow Feather Oasmeequin [Massasoit] made a treaty with (John) Carver [the first governor of the colony]. They elected an official while they were still on the boat. They had their charter. They were still under the jurisdiction of the king [of England]—at least that’s what they told us. So they couldn’t make a treaty for a boatload of people so they made a treaty between two nations—England and the Wampanoag Nation.

What did the treaty say?

It basically said we’d let them be there and we would protect them against any enemies and they would protect us from any of ours. The 2011 Native American copy coin commemorates the 1621 treaty between the Wampanoag tribe and the Pilgrims of Plymouth colony. It was basically an “I’ll watch your back, you watch mine” agreement. Later on we collaborated on jurisdictions and creating a system so that we could live together.

“Why do I call the Indians fools? Because they should have let the Pilgrims starve… The Indians were thanked: their land was stolen from them, they were massacred, and many lived out their lives in slavery. The consequence is that less than one percent of Americans have Native American blood, contrasted to 90 percent of Mexican Americans with Indigenous blood.” — Rodolfo Acuña in “CounterPunch“

STORY: Iroquois Thanksgiving Address

What’s the Mashpee version of the 1621 meal?

You’ve probably heard the story of how Squanto assisted in their planting of corn? So this was their first successful harvest and they were celebrating that harvest and planning a day of their own thanksgiving. And it’s kind of like what some of the Arab nations do when they celebrate by shooting guns in the air. So this is what was going on over there at Plymouth. They were shooting guns and canons as a celebration, which alerted us because we didn’t know who they were shooting at. So Massasoit gathered up some 90 warriors and showed up at Plymouth prepared to engage, if that was what was happening, if they were taking any of our people. They didn’t know. It was a fact-finding mission.

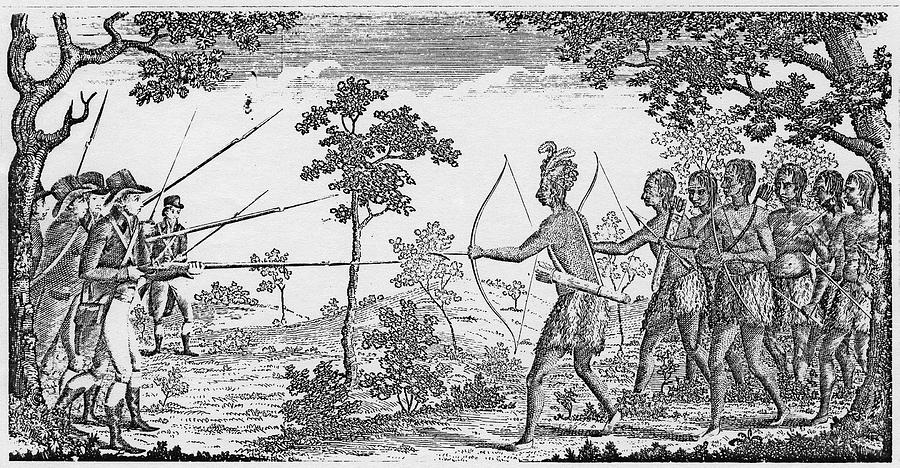

When they arrived it was explained through a translator that they were celebrating the harvest, so we decided to stay and make sure that was true, because we’d seen in the other landings—[Captain John] Smith, even the Vikings had been here—so we wanted to make sure so we decided to camp nearby for a few days. During those few days, the men went out to hunt and gather food—deer, ducks, geese, and fish. There are 90 men here and at the time I think there are only 23 survivors of that boat, the Mayflower, so you can imagine the fear. You have armed Natives who are camping nearby. They [the colonists] were always vulnerable to the new land, new creatures, even the trees—there were no such trees in England at that time. People forget they had just landed here and this coastline looked very different from what it looks like now. And their culture—new foods, they were afraid to eat a lot of things. So they were very vulnerable and we did protect them, not just support them, we protected them. You can see throughout their journals that they were always nervous and, unfortunately, when they were nervous they were very aggressive.

King Philip “Metacom” (c. 1637-1676) before launching King Philip’s War on the inhabitants of New England: “The English who came first to this country were but a handful of people, forlorn, poor and distressed. My father [Massasoit] did all in his power to serve them. Others came. Their numbers increased. My father’s counselors urged him to destroy the English before they become strong enough to give law to the Indians and take away their country. My father was also the father to the English. He remained their friend. Experience shows that his counselors were right.

“The English disarmed my people. They tried them by their own laws, and assessed damages my people could not pay. Sometimes the cattle of the English would come into the cornfields of my people, for they did not make fences like the English. I must then be seized and confined till I sold another tract of my country for damages and costs. Thus tract after tract is gone. But a small part of the dominion of my ancestors remains. I am determined not to live till I have no country.”

— King Philip from Norman B. Wood, “Lives of Famous Indian Chiefs,” Aurora, Illinois: American Indian Historical Publishing Co, 1906, 94-95

STORY: Indigenous Voices from the Northeast: Past, Present and Future

So the Pilgrims didn’t invite the Wampanoags to sit down and eat turkey and drink some beer?

[laughs] Ah, no. Well, let’s put it this way. People did eat together [but not in what is portrayed as “the First Thanksgiving”]. It was our homeland and our territory and we walked all through their villages all the time. The differences in how they behaved, how they ate, how they prepared things was a lot for both cultures to work with each other. But in those days, it was sort of like today when you go out on a boat in the open sea and you see another boat and everyone is waving and very friendly—it’s because they’re vulnerable and need to rely on each other if something happens. In those days, the English really needed to rely on us and, yes, they were polite as best they could be, but they regarded us as savages nonetheless.

So you did eat together sometimes, but not at the legendary Thanksgiving meal.

No. We were there for days. And this is another thing: We give thanks more than once a year in formal ceremony for different season, for the green corn thanksgiving, for the arrival of certain fish species, whales, the first snow, our new year in May—there are so many ceremonies and I think most cultures have similar traditions. It’s not a foreign concept and I think human beings who recognize greater spirit then they would have to say thank you in some formal way.

What are Mashpee Wampanoags taught about Thanksgiving now?

Most of us are taught about the friendly Indians and the friendly Pilgrims and people sitting down and eating together. They really don’t go into any depth about that time period and what was going on in 1620. It was a whole different mindset. There was always focus on food because people had to work hard to go out and forage for food, not the way it is now. I can remember being in Oklahoma amongst a lot of different tribal people when I was in junior college and Thanksgiving was coming around and I couldn’t come home—it was too far and too expensive—and people were talking about, Thanksgiving, and, yeah, the Indians! And I said, yeah, we’re the Wampanoags. They didn’t know! We’re not even taught what kind of Indians, Hopefully, in the future, at least for Americans, we do need to get a lot brighter about other people.

So, basically, today the Wampanoag celebrate Thanksgiving the way Americans celebrate it, or celebrate it as Americans?

Yes, but there’s another element to this that needs to be noted as well. The Puritans believed in Jehovah and they were listening for Jehovah’s directions on a daily basis and trying to figure out what would please their God. So for Americans, for the most part there’s a Christian element to Thanksgiving so formal prayer and some families will go around the table and ask what are you thankful for this year. In Mashpee families we make offerings of tobacco. For traditionalists, we give thanks to our first mother, our human mother, and to Mother Earth. Then, because there’s no real time to it you embrace your thanks in passing them into the tobacco without necessarily speaking out loud, but to actually give your mind and spirit together thankful for so many things… Unfortunately, because we’re trapped in this cash economy and this 9-to-5 [schedule], we can’t spend the normal amount of time on ceremonies, which would last four days for a proper Thanksgiving.

Do you regard Thanksgiving as a positive thing?

As a concept, a heartfelt Thanksgiving is very important to me as a person. It’s important that we give thanks. For me, it’s a state of being. You want to live in a state of thanksgiving, meaning that you use the creativity that the Creator gave you. You use your talents. You find out what those are and you cultivate them and that gives thanks in action.

And will your family do something for Thanksgiving?

Yes, we’ll do the rounds, make sure we contact family members, eat with friends and then we’ll all celebrate on Saturday at the social and dance together with the drum.

Updated 27 November 2024

Pingback: Praxis Center | The Legacy of Thanksgiving, and a Heritage of Lies |

Pingback: Mohegan Story: Healing of the Forest Little People

Pingback: Indigenous Voices from the Northeast: Past, Present and Future