Deforestation and the ongoing damming of pristine rivers for hydroelectricity threatens the wildest and most biodiverse corner of tropical Central America. The Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve (RPBR), in Honduras’ remote Moskitia Region, faces non-Indigenous land invasions from all directions, many government sanctioned and supported by multinational corporations. These incursions directly threaten the economic and environmental sustainability of indigenous communities throughout the region.

UPDATE: Deforestation shot up in 2020, nearly doubling the amount of forest loss over 2019. 2021 may be another rocky year for the biosphere reserve, with satellite data showing several “unusually high” spikes of clearing activity so far this year.

Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve: Paradise in Peril

Illegally logging the vast and once-impenetrable ancient forests, poaching endangered wildlife and fish, and slashing and burning jungle to create pastures, the new arrivals are forcing Pech and Miskitu inhabitants off their ancestral lands. The government of Honduras, elected under international condemnation after the 2009 coup d’état, stands by while trafficking in hardwoods, wildlife, archaeological artifacts, and drugs generate income for their multinational clients as well as impoverished and desperate peasants.

Multiple assertions are also made that the post-coup government of Juan Orlando Hernandez and their police and military apparatus, elected in a sham process supported by few countries in the world except for the Obama Administration, are working together with the traffickers, making any control impossible given present circumstances.

STORY: Honduras: Narcotrafficking Leads to Native Dispossession, Deforestation

The Biosphere Reserve

Located on the watershed of the Río Plátano on the Caribbean coast, the reserve remains as one of the few functional mountainous tropical rainforest ecosystems in Central America, where over 2,000 indigenous people have preserved their traditional way of life. Declared a World Heritage Site in 1982 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), it was the first of more than 700 throughout the world.

STORY: Papua New Guinea: Rainforest World of Sustainable River Guardians

Fauna and Flora

According to UNESCO, 39 species of mammal, 377 species of bird and 126 reptiles and amphibians have been identified in the Río Plátano. More than two dozen of these species are endangered–from the the giant anteater, Baird’s (Central American) tapir, jaguar, ocelot, puma, margay and jaguarondi to the Central American otter, Caribbean manatee, American crocodile, brown caiman, red brocket deer, harpy eagle, scarlet macaw, green macaw, military macaw, king vulture, great curassow, green turtle, loggerhead turtle and leatherback turtle.

As well, the RPBR contains the largest virgin broad leaf rain forest in Honduras. Some of the flora species that grow in this area include pine, mahogany, cedar, balsa, ceiba, guayacan, rosewood and sapodilla and rare orchids. According to Boise State University ornithologist David Anderson, the area encompassed by the reserve occupies an evolutionary keystone position in the Central American Isthmus that was central to the divergence of many vertebrate, insect, and plant lineages, facts just now beginning to be understood.

STORY: Lost White City “Discovered” in Honduran Jungle?

“Paradise in Peril” follows an expedition organized to document the destruction of this UNESCO World Heritage Site and collect testimony from the native peoples who rely on the Río Platáno for survival. Fewer than 400 individuals have ever completed this strenuous expedition from the rivers headwaters to the Miskito coast of Honduras.

Archaeological Heritage

The search continues in the Reserve to confirm the legend of Ciudad Blanca or White City that explorers since the conquest have sought without success. Some have posited the inhabitants were Maya, other not very credible analysts say Toltec and Mayan mythology points to the birthplace of the Plumed Serpent Quetzalcoatl (Toltec) or Kukulcan (Maya) in this region. Explorers noted carved white stones near deposits of white sand gave the city its name.

In 1939, US explorer Theodore Morde claimed (with no documentation or scientific study) to find the lost city and published a travelogue Lost City of the Monkey God, but was killed before he could organize an exploratory expedition, adding to the legend of the place.

Dr. Christopher Begley has studied the area in recent decades, documenting more than 200 archaeological sites, leading to speculation this area may have been a Mesoamerican [or more likely related to Nicaragua or South America) culture center between 800 and 1200 A.D, a time when the neighboring Maya experienced a corresponding decline. Begley related that the Pech and Tawahka people of Honduras have a myth about Wahai Patatahua (“place of the ancestors”) and Kao Kamasa (“the white house”) at the headwaters of the confluence of two rivers, by a pass through the mountains. In Pech mythology, their gods retreated to this wild and remote location in La Moskitia after the Spanish came.

Unfortunately, without proper protection these sites continue to be looted.

STORY: Maya Ruins at Tikal: A New Beginning at Winter Solstice

A Wilderness Forsaken

A climate of insecurity and lawlessness in Honduras’ remote north-east coastal region coupled with extreme poverty has led to drug-trafficking and invasion of landless peasants from the interior of the country. Honduras’ deforestation rate is one of the highest in Latin America and has led to a 37 percent reduction of forest cover between 1990 and 2005.

Narcotrafficking

The dense tree cover offers an ideal hideaway for smugglers who carve landing strips in the forest interior, as transit points for drug shipments flown from South America. The “narcos” – ruthless crime syndicates whose gang wars claim thousands of lives on city streets from Bogotá to New York – have brought cash to buy land, AK-47 machine guns to threaten locals, and chainsaws to clear the previously somnolent wilderness. Many have unfortunately called for urgent military intervention against the narcos for the entire Moskitia. Considering that drug trafficking seems to have connection to the highest offices in the Honduran government, this is a dangerous assertion. Interestingly, despite two regional US military bases, no significant pushback has registered yet.

MOPAWI, a main Miskitu conservation organization, has called for permanent and properly trained and equipped guards that would be accountable not to the government but toi regional Miskitu authorities. As well, they advocate an allowance for legal Miskitu-owned cattle and sustainable forestry ranges outside of the reserve core zone.

Hydroelectric Dam Proposals

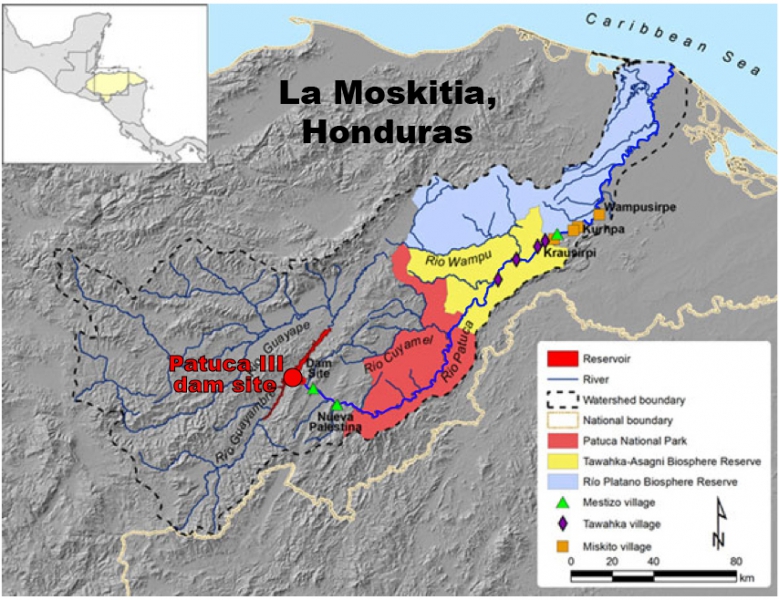

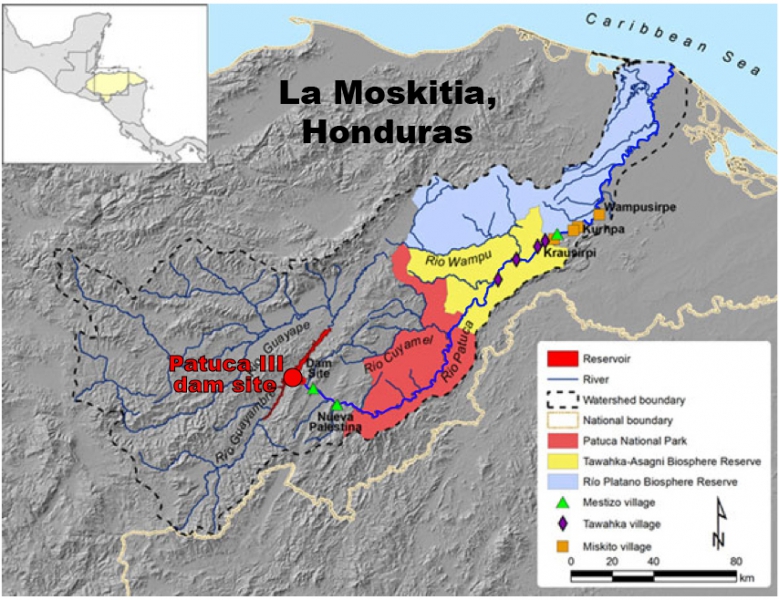

As International Rivers noted in their list of Dam-Threatened World Heritage Sites, “On 17 January 2011, the Honduran National Congress approved a decree for the Chinese engineering firm Sinohydro to construct the Patuca II, IIA, and III dams on the Patuca River, which flows adjacent to the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve. The proposed development involves flooding 42 km of intact rain forest, all of which was on the legislative track to either become part of the Patuca National Park or the Tawahka Asangni Biosphere Reserve.” The Patuca flows along the eastern edge of the reserve, and Indigenous communities depend upon it for drinking water, transportation, and to inundate the banks each year with fertile silt to grow plantains, oranges, cacao, cassava, beans, and rice.

As Lorenzo Tinglas, president of the Tawahka people’s governing council, said, “The river is our life…Any threat to the Patuca is a threat to four Indigenous Peoples—the Tawahka, Pech, Miskitu, and Garifuna—and we will fight to the death to protect it.”

According to Edgardo Benitez of the Green Alliance and the Platform in Defense of the Patuca River, the Tawahkas are under a particular amount of pressure . “This community of Tawahkas is at risk of extinction [if] the dam project at the Patuca River proceeds.”

STORY: Miskitu Legend: The Mangoes of the Dead

A Procedural Vacuum

The 2009 Honduran coup d’état that installed President Pepe Lobo Sosa (with US support) created a procedural vacuum for any environmental protection, institutionally weak and multinational corporation-friendly, with no framework for addressing the multiple threats. Without the ability of the government to relocate and compensate illegal settlers in the core zone, and a clearly articulated political willingness at the highest level to improve the management and conservation of Río Plátano, the World Heritage property finds itself in a process of rapid degradation.

Since June 2011, UNESCO has put the RPBR back on the World Heritage List in Danger. Recommendations have been put forward from the UN that would rectify deficiencies in the legal system, establish permanent monitoring, and undertake efforts for long-term management of the Reserve. To date, these efforts still lack institutional will and financial backing. The reality is, until the latest Juan Orlando Hernandez regime and its coup-installed government is taken out of power, this situation will continue to worsen.

Oversight from the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification of community-based logging in the area, done by Rainforest Alliance Smartwood and funded by the US Agency for International Development, has also been called into question. A statement provided to FSC-Watch by Frank Löwen, a forest expert previously employed in Rio Platano, alleges that some of Smartwood’s operations may have contributed to the Reserve’s problems, rather than helping overcome them.

Need for Indigenous Autonomy

Local Miskitu inhabitants have emphasized the presence of many logging companies in the zone, which obtain permits from the El Instituto Nacional de Conservación Forestal or ICF (formerly Corporación Hondureña de Desarrollo Forestal – COHDEFOR). One anonymous Miskitu commented, “Native people cannot obtain permits and every so often go to jail for cutting down a tree.” This contrasts with the fact that “the State never arrested anyone linked to the logging companies.” The person interviewed did not want to give his name because, “There have been murders and constant threats to leaders who make complaints against the logging companies.”

While the timber industry operates with explicit or implicit support of the authorities, the local inhabitants are forbidden access to certain zones and under restriction on hunting, fishing and wood and plant extraction. Nevertheless, the Miskitu and other local populations are developing actions towards recognition of their rights. Foremost, the people demand communities be granted communal land tenure deeds (and not individually). In addition, they advocate the Reserve and its management be placed in the hands of the Indigenous Peoples, with enforcement and protection from the state authorities, and financed by NGOs and governments abroad.

Carbon Offsets through REDD: Forest Protection Potential?

The possibility of protecting the Río Plátano through Global Warming Forest Carbon Offsets such as the Reduced Emissions From Deforestation and Degradation (REDD) marketplace has been asserted elsewhere as a sustainable and scalable funding mechanism for biodiverse forest protection, but has proven a seriously deficient mechanism in numerous cases with significant challenges and risks (link).

According to Erik Nielsen, Assistant Professor in Environmental Policy at Northern Arizona University, three of the key conditions for successful market-based forest carbon projects are 1) clear and secure land tenure, 2) absence of illegal deforestation, and 3) strong forest governance. None of these conditions exist in the Río Plátano. Of course, none of these requirements are even close to a reality in Honduras.

Any efforts to stem deforestation in general and create the conditions for some kind of payment for ecosystem services program would need to accomplish the following: 1) Provide territorial land title within the cultural zone to indigenous federations and delimit these areas; 2) Remove and prosecute illegal settlements within the cultural zone (as well as address the narco-trafficking issues) and 3) build local, regional and national networks for forest/wildlife management that empower local communities and institutions to both establish and enforce land use norms/regulation.

These are all challenging tasks necessary to build the institutional infrastructure necessary for sound management of the entire reserve. Presently, the World Bank funded Proyecto Corazón of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor and another German-funded project on the Río Plátano have the resources and institutional reach to halt externally-driven deforestation by achieving the above goals, but have as-yet been focused on buffer zone development projects and environmental education.

Again, until the successive corrupt coup governments, the latest being Juan Orlando Hernandez, is voted out of office, along with counterbalancing the power wielded by the international corporatocracy that dictates its moves, the Biosphere Reserve, and Honduras in general, are doomed.

Watch Paradise in Peril on Vimeo: http://vimeo.com/26209577

Show support for Robert Hyman’s film on Facebook: Friends of the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve

See Also: Jack Eidt, “Honduras: Patuca River Dams Threaten Indigenous Survival,” WilderUtopia.com

Updated 3 May 2021

Jack, this is extremely well done and describes the issues for those that want to know what is happening. Thank you so much!

Robert

Pingback: Model Cities: Corporatocracy Seeks Submissive Wild For Love | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Letter from COPINH to World Bank: "We reject the fraudulent REDD+ process" in Honduras | redd-monitor.org

Pingback: Honduras: Coastal Miskitu People Granted Land Rights | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Miskitu Portrait: Lobster and Life on Laguna Caratasca | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Blessing for La Moskitia, A Culture and Land in Transition | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Honduras: Narcotrafficking Leads to Native Dispossession, Deforestation | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Lost City "Discovered" in Honduran Jungle? | WilderUtopia.com