The Brazilian government’s militarized efforts to clean up Rio de Janeiro’s notoriously dangerous favelas is giving hope to some people living there, while others question the violent tactics and the whether it will make a difference. We provide counterpoint to Joshua Hammer’s 2014 investigation.

A Look Into Brazil’s Makeover of Rio’s Slums

By Joshua Hammer, Published in Smithsonian Magazine

Rodrigo Neves remembers the bad old days in Rocinha, the largest favela, or slum, in Rio de Janeiro. A baby-faced 27-year-old with a linebacker’s build and close-cropped black hair, Rodrigo grew up dirt poor and fatherless in a tenement in Valão, one of the favela’s most dangerous neighborhoods. Drug-trafficking gangs controlled the turf, and police rarely entered out of fear they could be ambushed in the alleys. “Many classmates and friends died of overdoses or in drug violence,” he told me, sitting in the front cubicle of the Instituto Wark Roc-inha, the tiny art gallery and teaching workshop he runs, tucked on a grimy alley in the heart of the favela. Rodrigo’s pen-and-ink portraits of Brazilian celebrities, including former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—whom Rodrigo met during the president’s visit to the slum in 2010— and the singer-songwriter Gilberto Gil, adorn the walls. Rodrigo might have become a casualty of the drug culture himself, he said, if he hadn’t discovered a talent for drawing.

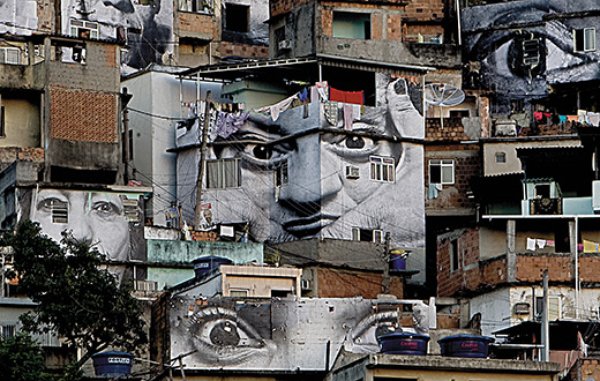

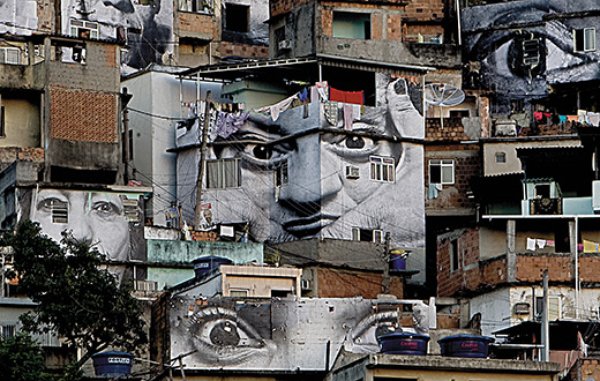

At 16, Rodrigo began spraying the walls of Rocinha and adjacent neighborhoods with his signature image: a round-faced, melancholy clown with mismatched red and blue eyes. “It was a symbol of the community,” he told me. “I was saying that the political system turned us all into clowns.” He signed the graffiti “Wark,” a nonsense name he made up on the spot. Soon the image gained Rodrigo a following. By the time he was in his late teens, he was teaching graffiti art to dozens of kids from the neighborhood. He also began to attract buyers for his work from outside the favela. “They wouldn’t come into Rocinha,” he said, “so I would go down to the nicer areas, and I would sell my work there. And that’s what made me strong enough to feel that I had some ability.”

In November 2011, Rodrigo hunkered down in his apartment while the police and military carried out the most sweeping security operation in Rio de Janeiro’s history. Nearly 3,000 soldiers and police invaded the favela, disarmed the drug gangs, arrested major traffickers and set up permanent positions on the streets. It was all part of the government’s “pacification project,” an ambitious scheme meant to bring down levels of violent crime and improve Rio de Janeiro’s image ahead of the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics.

Rodrigo had deep worries about the occupation, given the Brazilian police’s reputation for violence and corruption. But eight months later, he says that it’s turned out better than he expected. The cleaning up of the favela has removed the aura of fear that kept outsiders away, and the positive publicity about Rocinha has benefited Rodrigo’s artistic career. He landed a prized commission to display four panels of graffiti art at the Rio+20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development last June, and another to decorate downtown Rio’s port district, which is undergoing massive redevelopment. Now he dreams of becoming an international star like Os Gêmeos, twin brothers from São Paulo who exhibit and sell their work in galleries from Tokyo to New York. In a community starved for role models, “Wark” has become a positive alternative to the jewelry-swathed drug kingpin—the standard personification of success in the slums. Rodrigo and his wife have a newborn daughter, and he expresses relief that his child won’t grow up in the frightening environment that he experienced as a boy. “It’s good that people are no longer smoking dope in the streets, or openly carrying their weapons,” he told me.

Both murders and violent crime are down since the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) began operating in 2008. However, this improvement comes at a price. There are widespread reports of police abuse, including profiling favela residents as de facto criminals, endemic corruption, excessively violent tactics, torture and suppressing the lawful communication of protestors and journalists. Too often civilians are killed after being caught in the crossfire between UPP forces and drug traffickers. Amnesty International describes the aggressive and violent policing approach in Rio’s Maré complex of favelas as a “military occupation.” — Michael Holtzman, Truthout

STORY: Banksy: Satirical Outlaw, Graffiti Bomber, Mockumentarian

***

Brazil is a flourishing democracy and regional superpower, with a robust annual growth rate and the world’s eighth-largest economy. Yet its favelas have remained stark symbols of lawlessness, gross income disparities between rich and poor, and Brazil’s still-deep racial divide. In the 2010 census, 51 percent of Brazilians defined themselves as black or brown, and, according to one government-linked think tank, blacks earn less than half as much as white Brazilians. Nowhere are the inequalities starker than in Rio’s favelas, where the population is nearly 60 percent black. The comparable figure in the city’s richer districts is just 7 percent.

Now that the armed criminals are mostly gone, what is next for Rocinha? Many residents said they expected a “peace dividend”—a flood of development projects and new jobs—but nothing has materialized. “For the first 20 days after the occupation, they introduced all kinds of services,” José Martins de Oliveira told me, as we sat in the tiny living room of his home. “Trash companies came in, the phone company, the power company. People were taking care of Rocinha; then, after three weeks, they were gone.” — Joshua Hammer

For decades, drug gangs such as Comando Vermelho (Red Command)—established in a Brazilian prison in 1979—and Amigos dos Amigos (Friends of Friends), an offshoot, operated a lucrative cocaine-distribution network within the sanctuary of the favelas. They bought off police commanders and politicians and guarded their turf with heavily armed security teams. To cement the loyalty of the favelas’ residents, they sponsored neighborhood associations and soccer clubs, and recruited favela youths by holding bailes funk, or funk parties, on Sunday afternoons. These raucous affairs were often replete with underage prostitutes and featured music called funk carioca, which celebrated drug-gang culture and gang members who had died fighting the police. Bloody internecine wars for control of the drug trade could leave dozens dead. “They would block off the entrances of the alleys, making it extremely dangerous for the police to penetrate the favelas,” I was told by Edson Santos, a police major who conducted several operations in the favelas during the past decade. “They had their own laws. If a husband hit his wife, the drug traffickers would beat him or kill him.”

In 2002, a 51-year-old Brazilian journalist, Tim Lopes, was kidnapped by nine members of a drug gang near one of the most dangerous favelas, Complexo do Alemão, while secretly filming them selling cocaine and displaying their weapons. The kidnappers tied him to a tree, cut off his limbs with a samurai sword, then burned him alive. Lopes’ horrific death became a symbol of the depravity of the drug gangs, and the inability of security forces to break their hold.

Is drug trafficking and its accompanying violence just being redirected toward the poorer, outlying favelas that see even less public investment? And is “pacification” not so much a security campaign as it is a smoke screen designed to conceal something more insidious taking place beneath the surface? — Michael Holtzman

Then, in late 2008, the administration of President da Silva decided that it had had enough. State and federal governments used elite military police units to conduct lightning assaults on the drug traffickers’ territory. Once the territory was secured, police pacification units took up permanent positions inside the favelas. The Cidade de Deus (City of God), which had become infamous thanks to an award-winning 2002 crime movie of the same name, was one of the first favelas to be invaded by security forces. A year later, 2,600 soldiers and police invaded Complexo do Alemão, killing at least two dozen gunmen during days of fierce fighting.

Then it was Rocinha’s turn. On the surface, Rocinha was hardly the worst of the favelas: its proximity to wealthy beachfront neighborhoods gave it a certain cachet, and it was the recipient of hefty federal and state grants for urban redevelopment projects. In reality, it was ruled by drug gangs. For years, Comando Vermelho and Amigos dos Amigos battled for control of the territory: Comando controlled the upper reaches of the favela, while Amigos held the lower half. The rivalry culminated in April 2004, when several days of street fighting between the two drug gangs left at least 15 favela dwellers, including gunmen, dead. The war ended only after police entered the favela and shot dead Luciano Barbosa da Silva, 26, known as Lulu, the Comando Vermelho boss. Four hundred mourners attended his funeral.

Favela residents have expressed outrage against the militarization, impunity and abuse of power by police of the pacifying units (UPP), a favela-specific squadron practicing “proximity policing” to reclaim territory from drug trafficking gangs (although largely ignoring the areas controlled by the equally illegal paramilitary police mafias, known as milícias). Amarildo Dias de Souza, a poor laborer from the favela Rocinha, became emblematic of the 2013 protests after he was kidnapped, tortured and murdered by UPP officers who then dumped his body (never to be found) and hatched an elaborate cover-up scheme. — Tucker Landesman, Favela Issues

Power passed to Amigos dos Amigos, led in Rocinha by Erismar Rodrigues Moreira, or “Bem-Te-Vi.” A flamboyant kingpin named for a colorful Brazilian bird, he carried gold-plated pistols and assault rifles and threw parties attended by Brazil’s top soccer and entertainment stars. Bem-Te-Vi was shot dead by police in October 2005. He was succeeded by Antonio Bonfim Lopes, otherwise known as Nem, a 29-year-old who favored Armani suits and earned $2 million a week from cocaine sales. “He employed 50 old ladies to help manufacture and package the cocaine,” I was told by Major Santos.

But Jorge Luiz de Oliveira, a boxing coach and battle-scarred former member of Amigos dos Amigos, who served as one of the drug kingpin’s top security men, said that Nem was misunderstood. “Nem was an exceptional person,” Luiz insisted. “If somebody needed an education, a job, he would get it for them. He helped everybody.” Luiz assured me that Nem never touched drugs himself or resorted to violence. “He was an administrator. There are bigger criminals running around—like ministers, big businessmen—and they are not arrested.”

Unlike with the City of God and Complexo do Alemão, the occupation of Rocinha proceeded largely without incident. Authorities positioned themselves around entrances to the favela days in advance and ordered gunmen to surrender or face fierce reprisals. A campaign of arrests in the days leading to the invasion helped to discourage resistance. Around midnight on November 10, 2011, federal police, acting on a tip, stopped a Toyota on the outskirts of the favela. The driver identified himself as the honorary consul from Congo and claimed diplomatic immunity. Ignoring him, police opened the trunk—and found Nem inside. Three days later, police and soldiers occupied Rocinha without firing a shot. Today Nem sits in a Rio prison, awaiting trial.

***

It is only a 15-minute taxi ride from the wealthy Leblon neighborhood by the ocean to Rocinha, but the distance spans a cultural and economic gap as wide as that between, say, Beverly Hills and South Central Los Angeles. On my first visit to the favela, my interpreter and I entered a tunnel that cut beneath the mountains, then turned off the highway and began to wind up the Gávea Road, the main thoroughfare through Rocinha. Before me lay a tableau at once majestic and forbidding. Thousands of brick and concrete hovels, squeezed between the jungle-covered peaks of Dois Irmãos and Pedra de Gávea, were stacked like Lego bricks up the hills. Motorcycle taxis, the main form of transport in Rocinha, clogged the main street. (The mototaxi business was, until November 2011, tightly controlled by Amigos dos Amigos, which received a sizable percentage of every driver’s income.)

This new sense of safety comes at a cost: rising rent prices and gentrification. Rocinha’s traditional residents are moving out of some neighborhoods as middle (and soon, maybe upper) class Brazilians and foreigners move in. The catalyst for these changes has been the World Cup. Of the $11 billion in revenue Brazil is expecting from the World Cup alone, over 20 times what South Africa received in 2010, how much will Rocinha residents or for that matter any Brazilian civilians see? — Michael Holtzman

Read the Full Article on Smithsonian.com

Other Image Source: Eat Rio