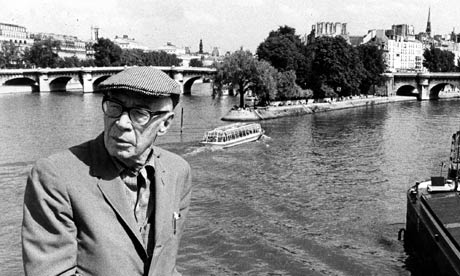

In 1934, Henry Miller, then aged forty-two and living in Paris, published his first book. In 1961, finally distributed in his native land, the book promptly became a best-seller and a cause célèbre. Today, the “controversies” dominate his legacy, including issues of censorship, obscenity, misogyny, and anti-Semitism, clouding the import of his words. Tropic of Cancer broke literary ground, mixing novelistic forms with autobiography, social criticism, philosophical reflection, and surrealist free association.

Henry Miller and His Creative Rage

Robert McCrumb in the Guardian UK: The shabby, 38-year-old American who arrived on the Left Bank in 1930 with a copy of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, and the manuscripts of two unpublished novels in his suitcase, was the quintessence of abject failure. All he had going for him – and it was everything – was creative rage (expressed in one letter as: “I refuse to live this way forever. There must be a way out”), mixed with the artistic vision of the truly avant garde. “I start tomorrow on the Paris book,” wrote Henry Miller. “First person, uncensored, formless – fuck everything!”

“There are only three things to be done with a woman. You can love her, suffer for her, or turn her into literature.” — Henry Miller

“I want to undress you, vulgarize you a bit.”

— Henry Miller, A Literate Passion: Letters of Anais Nin & Henry Miller, 1932-1953

Watch this video on YouTube

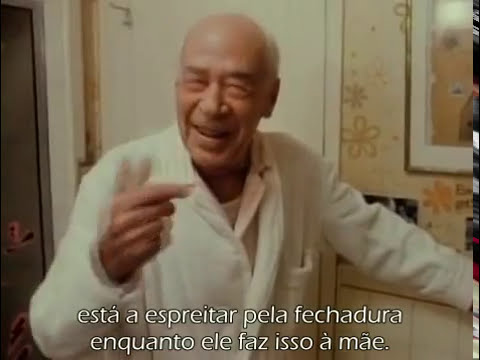

Henry Miller, Asleep & Awake – Tom Schiller, 1975

On Brooklyn in “Tropic of Capricorn” – “I saw a street called Myrtle Avenue,” Miller wrote, “which runs from Borough Hall to Fresh Pond Road, and down this street no saint ever walked (else it would have crumbled), down this street no miracle ever passed, nor any poet, nor any species of human genius, nor did any flower ever grow there, nor did the sun strike it squarely, nor did the rain ever wash it… Dear reader, you must see Myrtle Avenue before you die, if only to realize how far into the future Dante saw.” — Henry Miller

“To have her here in bed with me, breathing on me, her hair in my mouth—I count that something of a miracle.” — Henry Miller in “Tropic of Cancer” 1934

“I want to get more familiar with you. I love you. I loved you when you came and sat on the bed–all that second afternoon was like warm mist–and I hear again the way you say my name–with that queer accent of yours. You arouse in me such a mixture of feelings, I don’t know how to approach you. Only come to me–get closer and closer to me. It will be beautiful, I promise you.” — Henry Miller

STORY: Dirty Realism: The Anti-Social Satire of Charles Bukowski

“Paris is like a whore. From a distance she seems ravishing, you can’t wait until you have her in your arms. And five minutes later you feel empty, disgusted with yourself. You feel tricked.” — Henry Miller

From George Wickes in the Paris Review: Championed by critics and artists, venerated by pilgrims, emulated by beatniks, he is above everything else a culture hero—or villain, to those who see him as a menace to law and order. He might even be described as a folk hero: hobo, prophet, and exile, the Brooklyn boy who went to Paris when everyone else was going home, the starving bohemian enduring the plight of the creative artist in America, and in latter years the sage of Big Sur.

“I too love everything that flows: rivers, sewers, lava, semen, blood, bile, words, sentences. I love the amniotic fluid when it spills out of the bag. I love the kidney with it’s painful gall-stones, it’s gravel and what-not; I love the urine that pours out scalding and the clap that runs endlessly; I love the words of hysterics and the sentences that flow on like dysentery and mirror all the sick images of the soul…” — Henry Miller

From Alexander Nazaryan in The New Yorker: Paris’s carnivalesque, discordant quality—the rectilinear grandeur of the Jardin du Luxembourg pitted against the lurid, crooked byways of Montmartre—had been the subject of the poems of Baudelaire, the prints of Toulouse-Lautrec. Miller’s genius was to approach Paris with a combination of American enthusiasm and acquired French profligacy, with just a touch of German nihilism: “This Paris, to which I alone had the key, hardly lends itself to a tour, even with the best of intentions; it is a Paris that has to be lived, that has to be experienced each day in a thousand different forms of torture, a Paris that grows inside you like a cancer, and grows and grows until you are eaten away by it.”

“She rises up out of a sea of faces and embraces me, embraces me passionately— a thousand eyes, noses, fingers, legs, bottles, windows, purses, saucers all glaring at us an we in each other’s arm oblivious. I sit down beside her and she talks— a flood of talk. Wild consumptive notes of hysteria, perversion, leprosy. I hear not a word because she is beautiful and I love her and now I am happy and willing to die.” — Henry Miller in “Tropic of Cancer”

From Jeanette Winterson in the New York Times: There is beauty as well as hatred in “Cancer,” and it deserves its place on the shelf. Yet the central question it poses was stupidly buried under censorship in the 1930s, and gleefully swept aside in the permissiveness of the 1960s. A new round of myth making is ignoring it once more. The question is not art versus pornography or sexuality versus censorship or any question about achievement. The question is: Why do men revel in the degradation of women?

“Life moves on, whether we act as cowards or heroes. Life has no other discipline to impose, if we would but realize it, than to accept life unquestioningly. Everything we shut our eyes to, everything we run away from, everything we deny, denigrate or despise, serves to defeat us in the end. What seems nasty, painful, evil, can become a source of beauty, joy, and strength, if faced with an open mind. Every moment is a golden one for him who has the vision to recognize it as such.” — Henry Miller

H-T Open Culture

Updated 3 January 2023

Pingback: Picasso in Paris: Political Art is Dangerous | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Buckminster Fuller's World of Sustainable Design | WilderUtopia.com