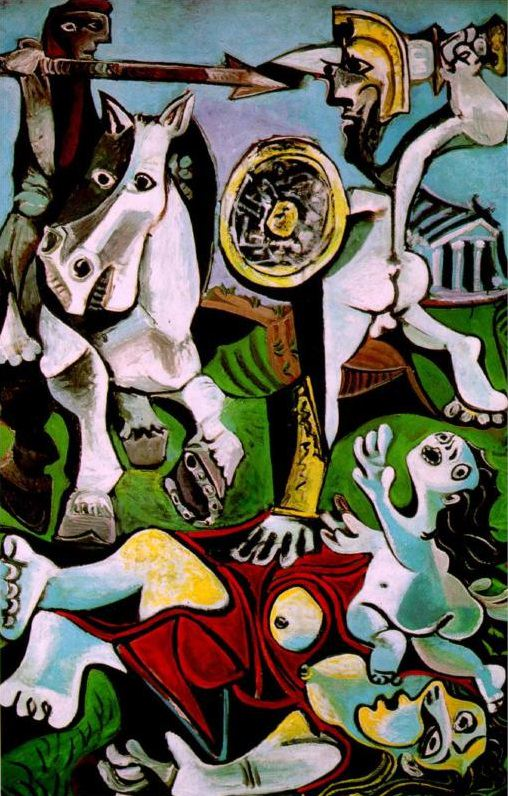

“Art is never chaste,” said Pablo Picasso. “Art is dangerous.” One of the 20th century’s greatest painters was born in Málaga, Spain, but Jonathan Jones argues he came into his own amid the sleaze and bohemianism of Paris – the only city that could have matched his peerless imagination.

Pablo Picasso: Spanish by birth, French at art

By Jonathan Jones, Published in the Guardian UK

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, stage designer, poet and playwright, probably the greatest artist of the 20th century, was French.

Hold on … don’t comment yet.

I am fully aware that Picasso was born in Málaga in southern Spain in 1881, that he started his artistic career in Barcelona and remained proudly Spanish all his life.

But the reopening of the Musée Picasso in Paris last autumn confirmed the French capital’s unique claim on this stupendously creative painter, sculptor and poet. His genius is so tangled up with the streets and garrets, palaces and attics of Paris, a city that he first visited in 1900 and whose artistic life he would take to new heights.

STORY: Paul Gauguin: Nature and Primitivism as Mythical Notions

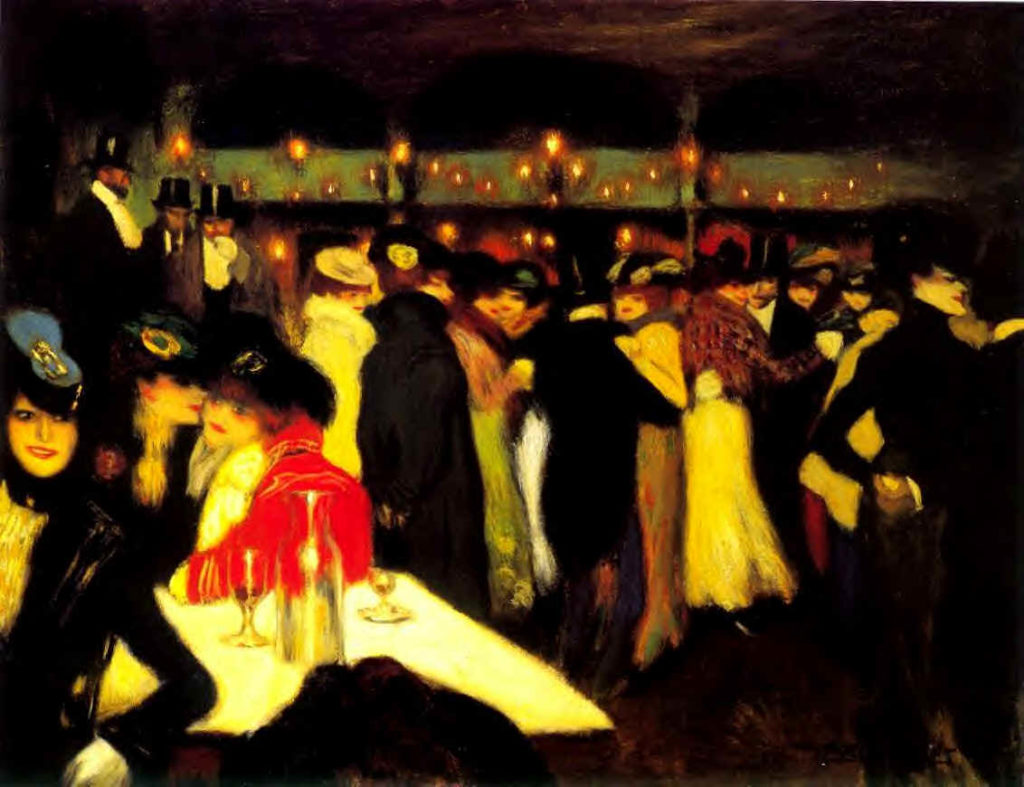

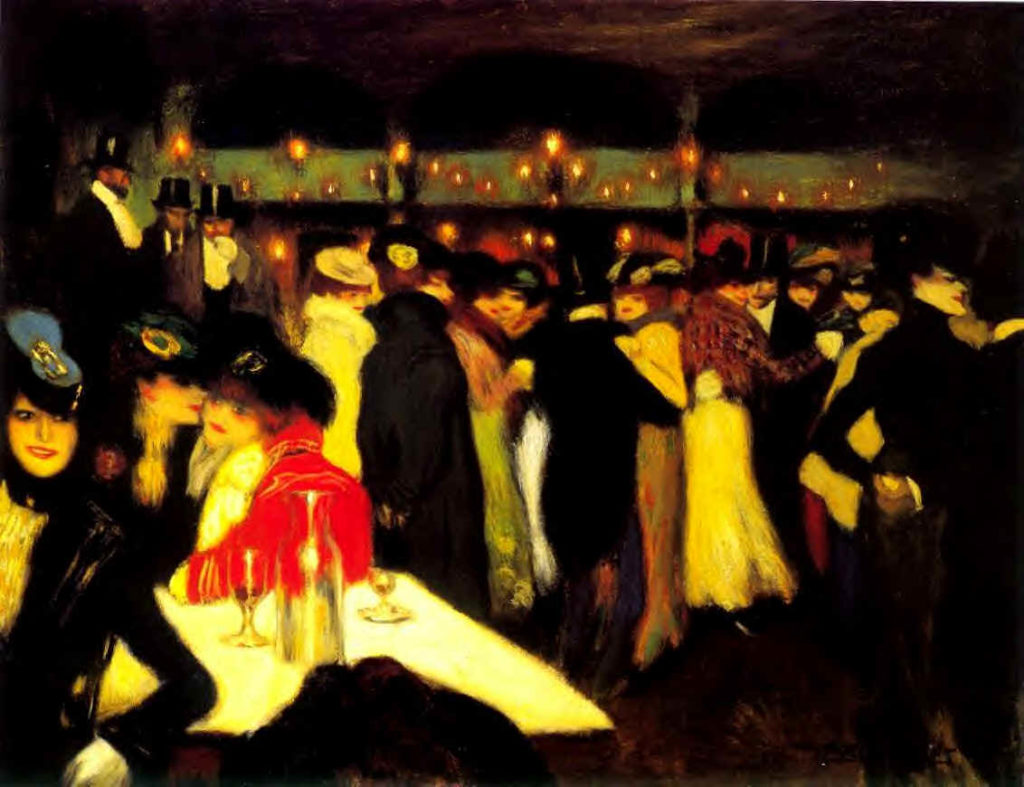

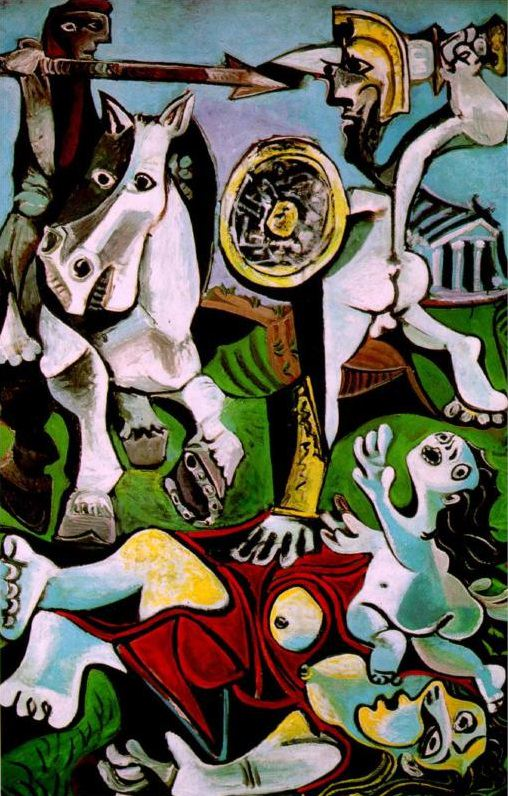

Picasso never forgot Spain, but he needed Paris to become a great artist. In 1900, the French capital was already crawling with modernists. The young Picasso emulated the raw nightlife scenes of Toulouse-Lautrec, and soon became fascinated by the art of Degas, Van Gogh and, most of all, Cézanne. Picasso’s “rose” period echoes the late works of Degas while Cézanne is the god of cubism. Picasso was eventually rich enough to buy a chateau at the foot of Mont Sainte-Victoire, thus owning, he boasted, the view his hero Cézanne had painted. He is buried there.

In Paris’ Montmartre: The “butte” was topped and tailed by nightclubs. The Moulin de la Galette, a real windmill turned cabaret, stood near the summit and the Moulin Rouge, a gimcrack fake, at the bottom. Thanks to its reputation as a place of cheap wine and cheap entertainment, Montmartre had been a favoured spot for artists since the late 19th century. Van Gogh lived there in the 1880s when he arrived from Holland; Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, Degas and Pissarro were all sometime residents.

But it was in the decade between 1900 and 1910 that Montmartre rose to its rickety peak. Almost every avant-garde artist of significance could at some point be found between the two moulins, Picasso, Matisse, Braque, Vlaminck, Derain, Modigliani, Brancusi, Gris and Marinetti among them. To the painters and sculptors could be added Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas, Apollinaire, the great art dealer Ambroise Vollard and Serge Diaghilev. — Michael Prodger

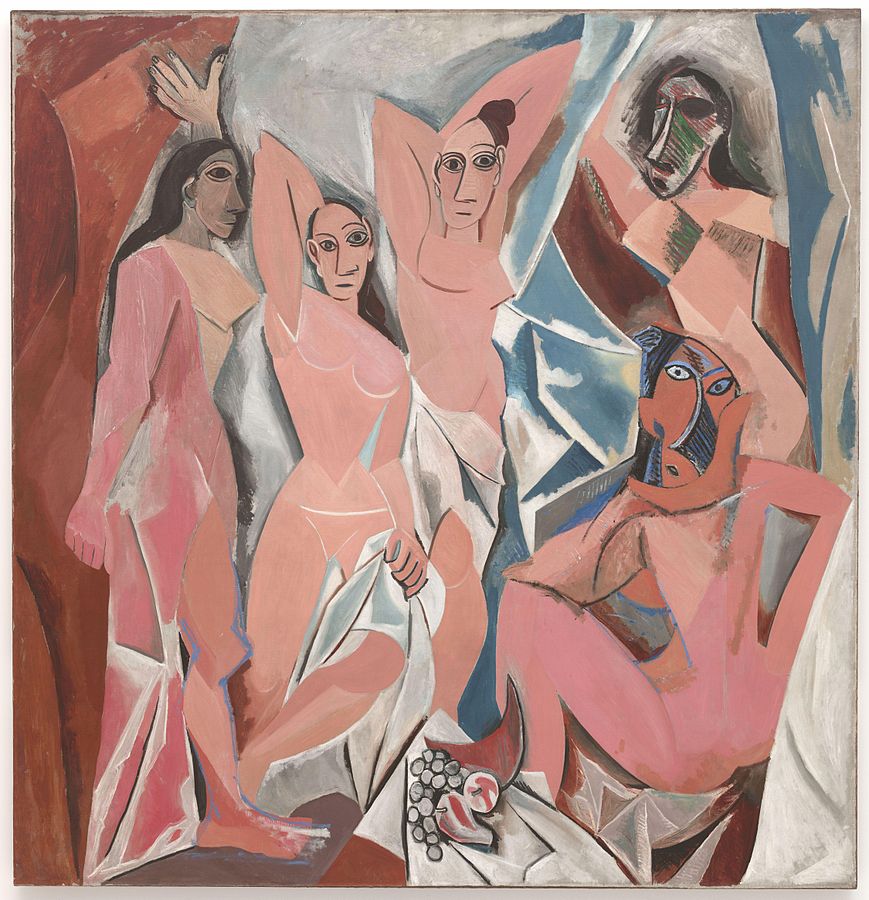

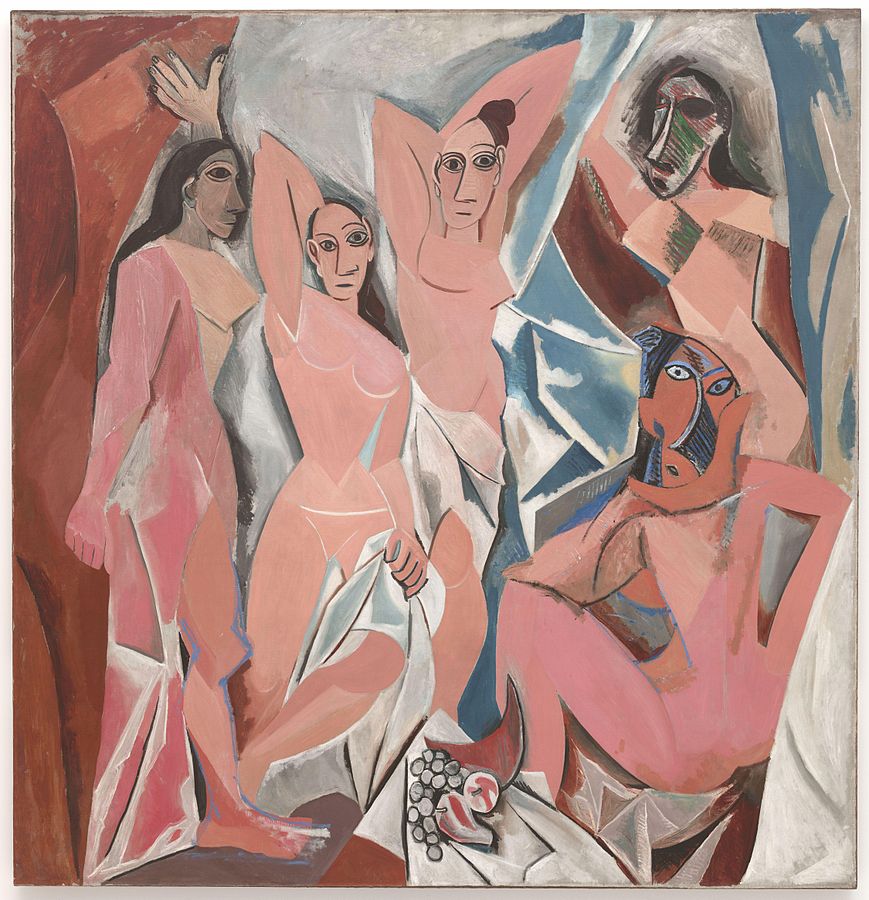

These great French artists fed Picasso’s changing styles, while the city itself – with its sleaze and bohemianism – inspired his imagination. In his 1907 masterpiece of sharp-edged menace Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Picasso takes the women who inhabit Toulouse-Lautrec’s Montmartre and reimagines them as brazen sexual terrorists.

What struck Picasso about African masks was the most obvious thing: that they disguise you, turn you into something else – an animal, a demon, a god. Modernism is an art that wears a mask. It does not say what it means; it is not a window but a wall. — Jonathan Jones in the Guardian

STORY: Henry Miller’s Free Association into the Surreal

Museum of Modern Art, New York. Via Wikipedia

A relationship with him, as Françoise Gilot wrote in her 1964 book Life with Picasso, was a “catastrophe I didn’t want to avoid.”

Picasso’s early time in Paris living in the ramshackle Bateau-Lavoir was riotous. Events like a banquet he gave in his studio for the untrained genius Henri Rousseau have become legendary. But Picasso’s Paris also includes the Left Bank and its cafes where, in the 1930s, he encountered the surrealist movement. While covering the relaunch of the Musée Picasso last year, I found the loft where he lived in the 30s, a stone’s throw from the famous Left Bank cafes where he talked art with radical intellectuals. It was also in this 17th-century attic that he painted Guernica.

We rightly see the greatest political artwork of modern times as a defense of Spain from Franco and Hitler – Picasso’s war painting portrays the destruction of Guernica in the Basque region by Nazi bombs. But it is a very French painting. It was created in his Paris loft and went straight from there to the 1937 Paris Universal Exhibition, where it was unveiled in the Spanish pavilion. The remains of this exhibition site – where Nazi and Fascist pavilions faced each other grimly – still exist beside the Seine.

As a sorcerer, [Picasso] found politics. That is the lingering suspicion – a suspicion that in the end the politics were gesture politics, and not to be taken seriously; that the political beliefs were rather shallow; that communism itself was more or less meaningless to this heedless party member; that the peace-mongering was little more than political posturing; that the trademark dove and all the drawing and lithographing for the cause (well represented in the exhibition) was so much agitprop; that the saluting of Stalin and his henchmen, however idiosyncratic, was at best deluded; that this was at bottom a mercenary affair, whereby the world-renowned painter was exploited by the party for his famous name, his fleet brush, and his financial donations; in short, that Picasso was a useful idiot. – Alex Danchev, The Guardian

STORY: Samuel Beckett, Confessions and the Human Condition

“What do you think an artist is? An imbecile who has only eyes if he is a painter, or ears if he is a musician, or a lyre in every chamber of his heart if he is a poet, or even, if he is a boxer, just his muscles? Far, far from it: at the same time, he is also a political being, constantly aware of the heartbreaking, passionate, or delightful things that happen in the world, shaping himself completely in their image. How could it be possible to feel no interest in other people, and with a cool indifference to detach yourself from the very life which they bring to you so abundantly? No, painting is not done to decorate apartments. It is an instrument of war.” — Pablo Picasso

Guernica was not merely painted in Paris but is steeped in art history, which Picasso taught himself in the Louvre. The great French tradition of history paintings, from Poussin to Géricault, which stands out in the Louvre collection, hovers behind Picasso’s great modern history painting.

STORY: Iannis Xenakis: Musical Sorcery Using Mathematical Totems

httpvh://youtu.be/xVEV7CfDngs

It was, of course, Guernica and the Spanish civil war that led to Picasso spending the rest of his life in France. The victory of Franco and destruction of Spanish democracy meant this principled artist would never go home. He stipulated that Guernica itself could only go to Spain after Franco died.

Picasso spent the second world war in Paris, quietly working and supporting the Resistance. His defiance of the Nazi occupation made him even more inseparable from the story of this city.

Alright, maybe Picasso wasn’t French. But he was definitely a Parisian.

Pingback: Paul Hindemith's Paean to Renaissance Art | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Geo-Fauvism: Waking to the Wild Earth Through Visual Art | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Creators of the Cool: Miles Davis and Gil Evans