In the sobering aftermath of World War I in Zurich, Dada preached a radical-yet-whimsical philosophy of creativity, a self-styled anti-art. Random and meaningless by definition, calculatedly irrational by design, for a short time the movement spread like revolt to the US and across Europe, voicing the bizarre protest of a brave new community of artists and writers.

Watch this video on YouTube

An Alphabet of German Dadaism

“There is a very wonderful bird mentioned here, called a nightingale,” said the emperor of China; “they say it is the best thing in my large kingdom. Why have I not been told of it?” — Hans Christian Andersen, from “The Nightingale”

Dadaism and Cabaret Voltaire

During World War I many artists, writers and intellectuals who opposed to the war, mostly Germans and a few Romanians, sought refuge from conscription in Switzerland. Zurich was a melting pot for exiles and on February 5th, 1916 the writer Hugo Ball and his partner Emmy Hemmings opened ‘Cabaret Voltaire,’ a rendezvous for the more radical element of the avant-garde. This venue served as part night club, part arts center where artists would exhibit their work to a backdrop of experimental music, poetry, readings and dance. Hence, a movement was born.

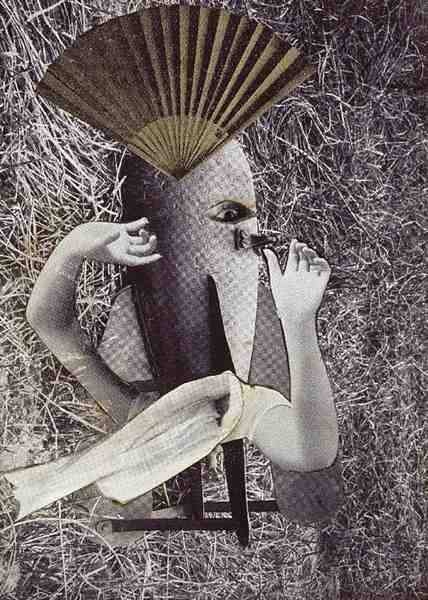

For many, Dada protested the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist interests, believed to be the root cause of the war, and against the cultural and intellectual conformity — in art and more broadly in society — that corresponded to the war. Hence, the movement rejected the logic and reason of bourgeois capitalism, and embraced irrationality. The movement after the war quickly spread to Berlin and Cologne, and later to Paris.

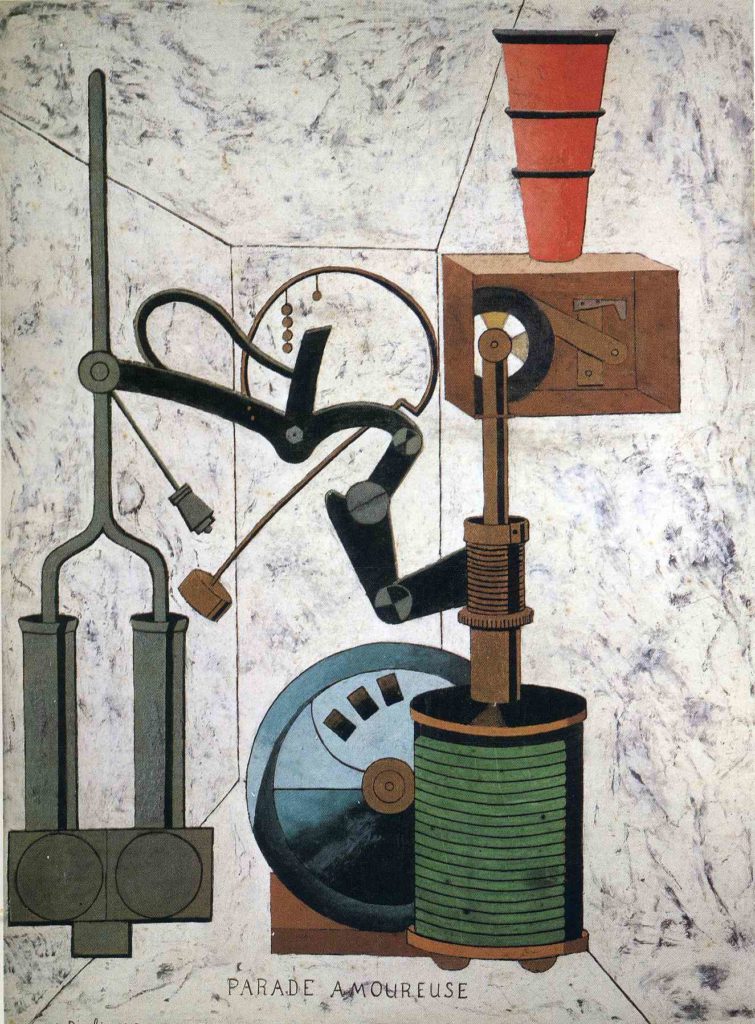

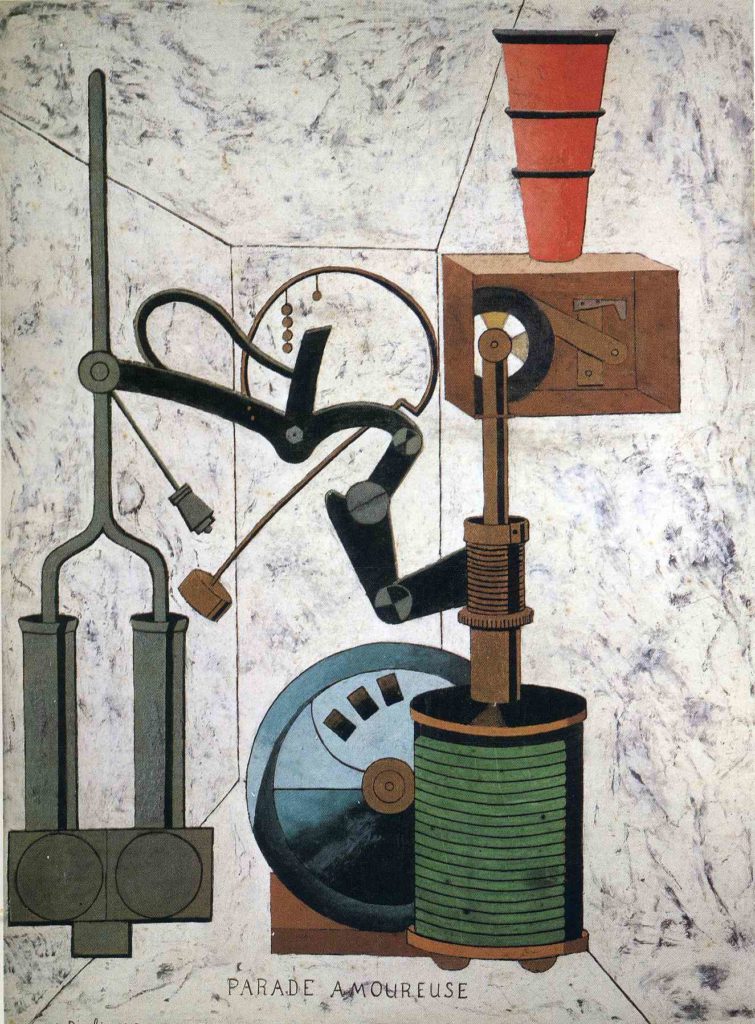

New York was another popular center for artistic exiles during WWI. Francis Picabia, a French painter associated with Cubism, first visited New York in 1913 for the opening of the Armory Show, a major exhibition of contemporary art from Europe and the US. There, he collaborated with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky), as well as Beatrice Wood and others, in expanding the radical, anti-art movement in the US. Having independent means, Picabia was able to spend the war years travelling between Europe and the US promoting modern art.

While living in New York, Picabia became fascinated by the myth of the machine as symbol of modernity. He expresses this in his ‘portraits mécaniques,’ a series of absurd fantasies which present mechanical contraptions as a metaphor for human relationships. In an article from the New York Tribune he states, “The machine has become more than a mere adjunct of life. It is really a part of human life…perhaps the very soul…I have enlisted the machinery of the modern world, and introduced it into my studio.”

STORY: John Cage: Dreaming in Sustained Resonance

Watch this video on YouTube

Ballet Mécanique accompanied by “Ballet Pour Instruments Mécanique et Percussion, Roll Two” by The New Palais Royale Orchestra & Percussion Ensemble, Maurice Peress

Early Abstract Dada Art Films

Following the theme of the machine mythos, Ballet Mécanique (1923–24) is a Dadaist post-Cubist art film conceived, written, and co-directed by the artist Fernand Léger in collaboration with the filmmaker Dudley Murphy (with cinematographic input from Man Ray). It has a musical score by the US composer George Antheil. However, the film premiered in silent version on 24 September 1924 at the Internationale Ausstellung neuer Theatertechnik (International Exposition for New Theater Technique) in Vienna presented by Frederick Kiesler. It is considered one of the masterpieces of early experimental filmmaking.

Watch this video on YouTube

Rhythmus 21 (1921) By Hans Richter

Preceding Léger, Hans Richter (April 6, 1888 — February 1, 1976) emerged as the most important film maker to come out of the German Dada movement before it moved to France and evolved into Surrealism. Dada rejected any and all bourgeois values associated with a society that seemed to be completely falling apart in the carnage of the first mass industrial war. This rejection even extended to previous avant-garde art movements like Impressionism, Expressionism, Fauvism, Symbolism and Art Nouveau.

What was the point of painting pretty pictures or writing poems when millions had died during the war and millions more in the influenza epidemic and famines that followed? Wasn’t the art establishment equally corrupt as the rest of society? Then the only answer to produce art and literature that mocked the idea of art itself. Dada exhibitions were considered a success if the audience stormed out, or even better started a mini riot. Such a movement was perfect for the early years of Wiemar Germany in the aftermath of the war.

STORY: Pablo Picasso: Dangerous Art and Political Posturing in Paris

Watch this video on YouTube

Filmstudie [1925] By Hans Richter

Richter made his first film in 1921 with “Rhythmus 21,” followed by “Rhythmus 23” and “Rhyhums 25” in alternate years as indicated by the titles. Apparently only the first film survives. These short films used abstract shapes randomly floating in space like a Mondrian painting come to life and had no plot or even any visible human cast. As indicated by the titles Richter saw the films in musical terms.

Though Richter pushed the Dada theme throughout his career, the zeitgeist of the movement headed on to Paris and around 1924 morphed into Surrealism and social realism, and the political chaos and capitalist oligarchs continued their malfeasance.

Thanks to Carl Welty and Chris Casady for recommending the experimental films.

Updated 31 January 2024

Pingback: Prefabricated Surrealism in 'Dreams That Money Can Buy' | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Visual Poems, Silent Dances of the Maquette Theatre | WilderUtopia.com