For the last 40 years, Detroiters have fled the once-majestic downtown core for the bucolic image of sprawling suburbia. Now an urban revival in the name of “Detroit Future City,” complete with forests, parks, farms and waterways, is planned to overcome the financial mismanagement and industrial blight that have plagued the city for far too long.

The Future of Detroit as the New Wilder City

Downtown Detroit, despite debilitating levels of de-industrialization, environmental degradation and urban poverty, has for several years been emerging from the ashes. Following a trend toward revitalization of urban areas in the US, Manhattan now sparkles with gentrification, and the downtowns of Chicago and LA are in transition, new residents and businesses seeking affordable property, walkable streets, central location, and sustainably-powered public transit. The still-struggling post-industrial cities, such as Cleveland, Buffalo, Baltimore and Detroit, have seen a slower, yet determined resurgence.

Many Detroit neighborhoods have adopted forward-thinking strategies in urban revitalization and economic recovery, despite continuing high crime, impaired police, fire, and utility services. Market momentum in Detroit’s core is palpable and the broadly supported Detroit Future City plan provides an excellent blueprint for growth and investment. Strategies such as significant investment in the downtown core, proliferation of ecological urbanism such as urban farming, reforestation, creation of parks and open space blended with commercial development and farmers markets all have significant support. The old standard redevelopment tools, casinos and sports stadiums, should be mixed with housing of varying densities and income-levels. A true renaissance can happen by managing gentrification with room for existing residents, artists and students, all connected with a downtown People Mover and Woodward Avenue Light Rail.

After Michigan’s Republican Governor placed Detroit’s Democratic-leaning city hall under the control of an emergency financial manager, they have filed for the largest municipal Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection in US history. Many entities have suggested that public pensions and the works of art at the Detroit Institute for Arts are on the table to pay off the $18.5bn debt burden to Wall Street creditors. This would be exactly the wrong thing to happen: balance the budget on the backs of working people who need to invest in life in Detroit, while poaching the few amenities that make the city special.

A better incubator for a sustainable future for Detroit, however, can be found it its ongoing urban rethink.

A Working Plan for “Detroit Future City”

In December 2012, Mayor Dave Bing and the Detroit Works project attempted to address the city’s woeful environmental justice record and lagging employment and real estate market. Urban neighborhoods needed a comprehensive environmental vision, facing massive pollution from auto plants, the Great Lakes Works steel mill, the Marathon oil refinery coating residences with tar sands petroleum-coke dust, a wastewater treatment plant dumping raw sewage into the Detroit River, as well as nitrous oxide emitted from one of the nation’s largest solid waste incinerators, Detroit Renewable Power. While the nascent downtown revival has a long way to go in overcoming this history, it will be a first step to creating the jobs, economic activity and tax revenues needed to underwrite broader recovery.

The city crafted a 350-page plan known as the “Detroit Future City”. The 50-year plan includes a number of sustainable ideas like building “blue and green infrastructure” to help address water and air-quality issues, creating new open space networks that incorporate habitat for local wildlife, and diversifying the city’s public transportation modes. The report calls for adding new, large areas of greenspace, but it’s also emphatic about the need to reuse old buildings.

The Kresge Foundation’s Detroit Future City initiative will provide $150m to create more concentrated economic development, reuse 100,000 vacant plots and add parks. In addition, the W.K. Kellogg and Ford Foundations have pledged millions. Invest Detroit, the Detroit Downtown Partnership, and the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation have nurtured these deals and the broader revival for years.

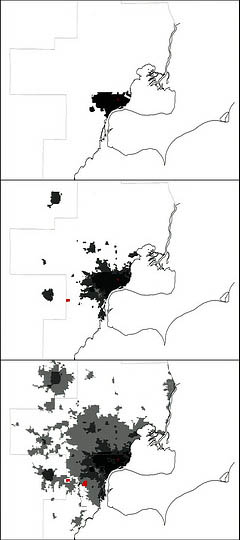

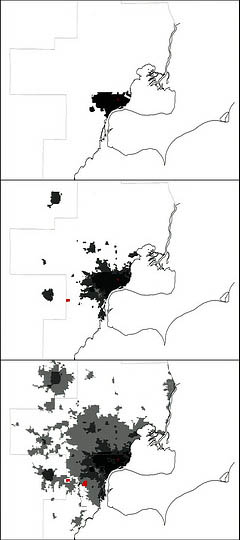

Detroit Sprawl, the People Mover and Light Rail

The Motor City has had an uneasy relationship with public transit beyond buses. Moreover, the car-addicted parking lot and freeway sprawl that dominates the region has encouraged economic development to speed out into the leafy suburbs for the last 40 years. Plenty of cities have pension obligations, but what Detroit lacks a tax base. A study released by the Brookings Institution this year found that less than a quarter of Detroit jobs are within 10 miles of the central business district, the worst job sprawl in the country.

The 2.9-mile Detroit People Mover was intended to be the downtown distributor for a proposed city and metro-wide light rail transit system for Detroit. An automated people mover system using the same technology as Vancouver’s SkyTrain and Toronto’s Scarborough RT line, it operates on a single set of tracks, and encircles Downtown Detroit. While expensive on a per-mile basis, it was intended as the first phase of a much more comprehensive system, which has been slow in arriving at the station.

This year, a consortium of regional private and public businesses and institutions announced the Woodward Avenue Light Rail Line, now called M-1 Rail. The $137 million, 3.3-mile-long streetcar line will run along part of the same route connecting the downtown Detroit People Mover to the proposed SEMCOG commuter rail in New Center. M-1’s plan is a mostly curbside-running, fixed-rail streetcar circulator system, co-mingled with traffic, with 11 stops between Congress Street downtown and Grand Boulevard in Midtown. It will run in the median at its north and south ends.

Yes, clearly, this small investment will not revolutionize transit in Detroit. Yet, massive mistakes, like its present expressway to nowhere landscape must be undone slowly, district-by-district. Los Angeles has experienced a similar process, but progress has been made. With continued investment in existing transit to connect with the new lines, facilities integrate and serve the population at large.

A Downtown Revival (Albeit From Above)

Dan Gilbert, founder of mortgage provider Quicken Loans, has helped to transform a significant portion of downtown Detroit, whether one believes this form of investment has a net regional benefit or not. In 2007, Gilbert moved the firm’s headquarters from suburban Farmington Hills to downtown. Since then, he has brought more than 8,000 employees into the central core and purchased dozens of buildings. This is progress.

The firm is now the third-largest landholder in the city of Detroit, behind city government and General Motors. Gilbert’s purchases and building plans are all part of his “Opportunity Detroit” vision, “a lively live-work-play district in the heart of the city based around entrepreneurial companies in the digital economy.” Some argue this will not improve the city at large. Yet the creation of well-paying jobs downtown, that some might take public transit to, from possible new housing opportunities created nearby, will serve to revive the fortunes of the neighborhood.

Detroit’s often vacant high-rise office blocks around Campus Martius, the plaza pictured above, also have some of the US’s best examples of Art Deco architecture. The downtown is a National Register Historic District with more than 50 landmarked buildings. In its Eastern Market, which opened in 1891, Detroit has the longest-running farmers’ market in the US. Like an oasis, Eastern Market is coming back to life amid the urban “food desert” that covers most of the city.

For the first time in a century, Chrysler, one of Motown’s Big Three, has opened an office in Detroit. Other substantial hirers include Blue Cross Blue Shield, which now employs 4,000 people in downtown Detroit.

Midtown Grassroots: Masonic Temple – Cass Corridor

Despite the marginalization of the neighborhood, it is home to one of the US’s finest symphonies and the aforementioned institute of art. The latter features Diego Rivera’s “Detroit Industry Murals” and Vincent van Gogh’s “Self-Portrait,” among others.

Sue Mosey, president of the community development organization Midtown Detroit Inc., is leading a revival of driven by four major anchor institutions — expanding the Henry Ford Hospital and Detroit Medical Center, adding biomedical and technology research facilities at Wayne State University, and the renovation of GM’s old Argonaut Building for the College for Creative Studies. She also helped lure Whole Foods to the area, which may not serve the legions of poor in the surrounding neighborhoods, but access to healthy food nearby might inspire others to provide lower cost alternatives.

Moreover, Detroit’s neo-gothic Masonic Temple towers over the Cass Corridor, a midtown stretch containing two historic districts and some of the city’s most striking design. The area was home to the original Cadillac plant, which burned and was rebuilt in 1905. As well, it hosted the Cass Corridor Art Movement in the mid-60s to late-70s, thriving in the slums near Wayne State. In the wake of the 1967 civil unrest, the “urban expressionism” of the neighborhood disintegration took up the broken pieces, physical and emotional, of the increasingly abandoned environment and fashioned them into rambunctious works of art.

The Masonic Temple, built in 1926, is the largest of its kind in the world, standing as a testament to the teeming behemoth of a city that Detroit once was. White Stripes musician Jack White’s recent move to pay off its back taxes has ignited the hopes of infusing the neighborhood with some of its former glory. The city also has plans for a new Red Wings hockey stadium to be built kitty corner to the temple.

A City Rediscovers its Landscape

For past generations, Detroit was a center of technological innovation in the US. For the last 40-years, it has been the poster-child of industrial senescence and blight, beset with poverty and racial discord. It is time to heal the wounds and create a new story: a city rediscovering its landscape and neighborhoods, growing its food, walking its streets in harmony.

Updated February 23, 2016

Pingback: Detroit’s Sprawling Legacy: How to Overcome the Automobile? – By Jack Eidt

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/nancy-kotting/our-architecture-ourselve_b_7223446.html?utm_hp_ref=detroit&ir=Detroit

Pingback: Detroit Works: Urban Farming and Reforestation as Neighborhood Preservation

Pingback: Detroit Heidelberg Project – Renaissance Through Urban Art