The LA River, an over-engineered concrete “water-freeway,” is undergoing a long-term greening and revitalization. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 2014 recommended an ambitious $1-billion plan to restore an 11-mile stretch of the Los Angeles River from downtown through Griffith Park. In addition, the planning for a 32-mile greenbelt, as well as numerous individual projects, promises to improve the health of the ecosystem and the value of the river as a regional public amenity, while managing flows and protecting properties.

A River Lost: 51 Miles of Concrete

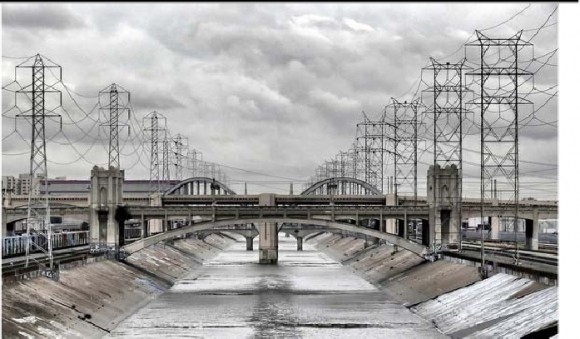

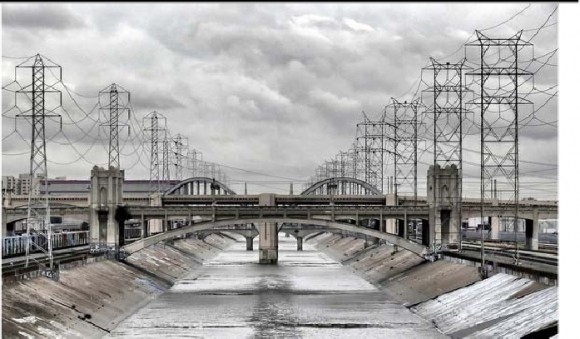

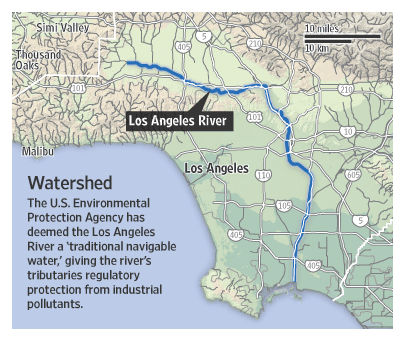

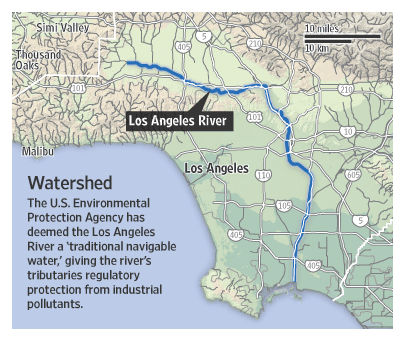

The Los Angeles River, once the fount of life for generations of people and wildlife, had been turned into a 51-mile cement flood control gulch splashed with reclaimed wastewater, storm drain puddles of lawn fertilizer, soapsuds and plastic bags. Encompassing 830 square miles of urban watershed from the San Fernando Valley to the Port of Long Beach, after catastrophic flooding in 1914, 1934 and 1938 the US Army Corps of Engineers dug it a concrete straightjacket, transforming it into a flood control channel.

This straightening, deepening and widening, adding the Hansen and Sepulveda Dams and massive flood control reservoirs, enabled the post-war real estate boom to sprawl all over lowland Los Angeles, safe from the seasonal rise in waters. As a result, the river as bringer of life disappeared from public consciousness, but for occasional movie car chases.

An Ecological Conundrum

Unfortunately, the jacketed river could no longer splash across its basin, once known for occasionally jumping southern-flowing banks, heading west into the Ballona Creek to the sea at Marina del Rey. The concrete-enforced drainage, almost devoid of plant and animal life, no longer replenished the aquifer with water, the soils with nutrients, and the beaches with sand. The county designed the storm sewers, however, to empty into the channel, transforming the river into and intermittent stream of fluorescent, green-black slime, amid human garbage.

Consider the city’s further environmental conundrum where the semi-arid Mediterranean climate pours as much of the scarce rainwater as possible, delivered from the sky for free, into the storm sewers, through the river, and into the Pacific. At the same time, the city pays dearly to import water by aqueduct from up to four hundred miles away. In the words of the writer Jenny Price: “Call it watering the ocean, by draining watersheds across the West.”

Moreover, L.A. developed giving private property privilege over public spaces, historically setting aside little public park space per capita—according to the Trust for Public Land, a paltry 6.2 acres of park space per 1,000 residents (Compare 28 acres in Portland, OR). The poorest areas suffer the worst shortages of neighborhood park space, enjoy the least private green space, and lie farthest from ample mountain parks on the edges of the city. The concrete channel turned the basin’s most logical site for green space, and the city’s major natural connector, into an outsize open sewer that carved a no-man’s-land through many of the city’s most fragmented and park-starved areas.

“You see cinnamon teal, which are marsh ducks, in the L.A. River because there are no more marshes, and I feel like, it’s like the same [as] with people: Only the tough survive in Los Angeles. Last year we did about 25 samples of fish in the river — there’s a lot more fish than most people would have imagined, carp a foot and a half long, all through the Glendale narrows.” – Lewis MacAdams, co-founder of Friends of the Los Angeles River

52 Miles of Concrete, Documentary Short by Hannah Sim and Mark Steger

The Los Angeles River Revitalization Master Plan

Twenty-seven years ago, civic leaders, led by poet Lewis MacAdams, founded Friends of the Los Angeles River (FoLAR) as a continuing work of art (and public education as well as politics) to bring the Los Angeles River back to life. The earth art of Robert Smithson and the political provocations of the German artist and Green Party co-founder, Joseph Beuys inspired the movement.

After a long process of educating city residents and the political establishment, in 2007 the LA River Revitalization Master Plan stipulated twenty major opportunity areas, promising to restore habitat, treat urban storm runoff, improve water quality, creating a network of parks and a continuous River Greenway, which will spark economic growth to newly-greened neighborhoods along the 51-mile river.

The plan intends to remove concrete and restoring a soft-bottom where possible to establish a connected riparian corridor. Neighborhoods would be integrated with the river through a network of greened streets, sidewalks, and pathways. Compromises between ecology and flood control could be implemented through collaboration between the City and County of Los Angeles, the Army Corps of Engineers and numerous regional and local non-profit organizations and public stakeholders in the area.

[Even] the most well-meaning plans, and the master plan, which is a great document, tend to be based around human rather than natural [needs]. If you think of the river as its banks, then it becomes a little like the San Antonio River Walk. One of the biggest challenges is to stay focused on the river as a river. This isn’t just for the humans. It’s for the four-legged ones and the swimming ones and the flying ones. — Lewis MacAdams

The Challenges of Watershed Rethinking. The plan is ambitious and not without its detractors, with a timeline of 20 to 50 years and a cost in the billions. There are constraints of land availability, reluctant stakeholders, a dearth of funding sources, and bureaucratic hurdles. It did not help that the Army Corps plowed under dozens of acres of wildlife habitat at the Sepulveda Basin earlier this year, showing their methods may not have changed much over the years.

As well, we must remember the success of revitalizing the river itself depends upon adoption of a comprehensive plan for the watershed going back to its headwaters in the mountains. We must reduce storm flows and polluted runoff from upstream, dealing with runoff at its source. Thus it requires planning for point-source filtration and aquifer recharge for a watershed paved over with impervious surfaces. The City of LA has Low-Impact Development and Green Streets programs that advance these notions with implementing best management practices for runoff management, slowing and filtering the flow, allowing algae, tree roots, and aquatic species to thrive. More ambitious programs, however, should be implemented that deal with retrofitting the landscape, rather than just regulating new development.

Following are a number of completed and proposed projects that will slowly imbue the city’s former life-line with its indigenous shades of green and blue.

Special Projects: LA River-Arroyo Seco Confluence

A recent study by USC architecture student Yingjun Hu, sought to re-envision the degraded riverfront at confluence of the Arroyo Seco and LA River near Cypress Park, an area where train, freeway and urban neighborhoods are jumbled on top of each other without regard for the potential blending, in particular with nearby Elysian Park. His proposal intended to transform the area into a multi-functional corridor of significant natural and cultural value through widening the river, improving foot and bike paths, re-vegetating river edges with bio-swales, and encouraging redevelopment of surrounding neighborhoods.

Hu studied precedents such as Buffalo Bayou in Houston, which transformed a neglected bayou drainage system of downtown Houston into 23 acres of new parkland with extensive bike trails and pedestrian connections. The design used stepped gabion cages made of crushed concrete, which allowed tree roots and benthic riparian plant communities to control erosion and sustain the future hydrologic actions. He also compared it to the Guadalupe River system in San Jose, California, Kallang River Bishan Park in Singapore, and the First San Diego River Improvement Project, all which link urban areas through bike and pedestrian trails and has restored life to the river ecology.

Chinatown-Cornfields Area

Piggyback Yard

In a plan put forth by FoLAR and a group of designers, the Piggyback Yard Plan intends to create a thriving transit-oriented business district and 130-acre public park just with connectivity to downtown, Union Station, Lincoln Heights and Boyle Heights. The site at present is a 125 acre intermodal rail facility where containers are humped between flat cars and 18 wheelers. The plan calls for reshaping the river channel, creating a soft bottom, slowing down its flow to allow vegetation to grow within its banks and filtering water, forming a thriving ecosystem. While the site remains in the clenched hands of Union Pacific and funds to complete such an endeavor are as yet speculative, the possibilities remain endless.

This is vastly oversimplified, but people are more afraid of flood downstream. It’s deeper than rational, and that’s part of the issue. [FoLAR fought higher walls] because we didn’t want to separate people from the river. We wanted the river to have a place in people’s lives. But people were scared, and there was some reality to it, no doubt — but it was exploited. – Lewis MacAdams

Ongoing River Revitalization

Tujunga Wash Greenway. One of the first restoration efforts, in 2007 engineers created a small, duplicate stream next to the larger paved channel in the San Fernando Valley near Van Nuys on a tributary of the LA River. This greenway diverts some of the main channel’s water into a more natural gravel streambed surrounded by native vegetation and a cycling path. The project’s designers boast that the new stream helps absorb some of the Tujunga Wash’s riverwater into the aquifer, instead of flushing it out into the ocean.

Just down from the restored Valleyheart Greenway is a proposal to build 200 condominiums and six four-story buildings on the river in Studio City threatens one of the last open stretches of riverfront. The Los Angeles River Natural Park has been proposed as an alternative for the 16-acre site by Community Conservation Solutions, providing trails, golf and tennis, building a system of natural wetlands that could capture and treat runoff.

Tujunga Watershed Plan. Other more radical visions include a study by The River Project for a comprehensive watershed plan for the Tujunga and Pacoima Washes reaching into the San Gabriel Mountains north of Los Angeles. considering the hydrologic cycle begin in the mountains, any river revitalization should consider the source of the fows before reworking downstream sections. This effort is ongoing.

Glendale Narrows Riverwalk. Located across the river from Griffith Park, the phased Riverwalk will include about a mile of recreational trail, park, equestrian facility and bridges. The first phase opened last December, with two more in various stages of financing.

North Atwater Park Expansion and Creek Restoration. This $4 million project restored Atwater Creek with a suite of stormwater management best practices. The project, opened in April 2012, re-graded an 800-foot narrow open channel, reshaped it, and removed invasive plant species to improve water flow. Structural stormwater best management practices including a trash removal device and native vegetation were implemented to improve the quality of water draining from the 60-acre sub watershed out to the LA River.

Taylor Yard Complex – Taylor Yard is a 247-acre former railyard with over two miles of Los Angeles River frontage. Includes restoration of riparian habitat, naturalization of the river channel and creation of a large water quality treatment wetland. Some portions of the site have been developed into the Rio de Los Angeles State Park, and organizations such as The River Project advocate for acquisition of the remaining parcels to complete the vision.

The Northeast LA Riverfront Collaborative has created the Northeast Los Angeles River Vision Plan to push for a comprehensive Riverfront District in the area between Glendale and Chinatown.

Lower LA River Watershed. This entirely urbanized, park-poor watershed drains into approximately 250 miles of storm drains. Miraculously wetland habitat remains in Compton Creek’s earthen bottom, the LA River Estuary (downstream of Willow Street in Long Beach), and constructed wetlands exist at the Dominguez Gap Wetlands (on the East bank of the River downstream of the Del Amo Bridge). The Council for Watershed Health has a number of improvement projects ongoing in the Compton Creek area.

A Long Winding Way Back

Funding, a sluggish economy, the entrenched mindset of railroad engineers, industrial interests, and politicians all make this revitalization a continuing challenge. Gentrification also will affect existing low-income residents and reduce the stock of affordable housing. But the projects are being drawn up, financed and developed, one-by-one. In the words of Lewis MacAdams, it is a forty year artwork. We must have patience.

The Council for Watershed Health supports healthy watersheds for Southern California by serving as a center for the generation of objective research and analysis. The Council has established a platform for meaningful collaboration among governmental organizations, academic institutions, businesses and other nonprofit organizations with a vested interest in clean water, reliable water supplies, ample parks and open spaces, revitalized rivers, and vibrant communities.

Founded in 1996 by leading environmental activist Dorothy Green and others, the Council performs research and educates experts and the public about water, watersheds, and sustainability. The Council’s impartial, trustworthy expertise and analysis connects a diverse set of groups with overlapping missions in an effort to drive polices that will continually improve watershed quality. For more information and a calendar of events in the region, see: http://www.watershedhealth.org/.

Pingback: LA River Revitalization

Pingback: East West Link: many losers, no obvious benefits | Ideas for a greener environment, a fairer society and a future driven by sustainability

Pingback: LA River: An Urban Ecosystem Makeover in Transition | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: LA River

Pingback: Framed: Chris Turnham’s Prints Hone In on L.A.’s Easterly Neighborhoods |

Pingback: LA River Must Transform as Watershed, Transport Corridor | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: In Several Decades, Los Angeles Will Be Habitable for the First Time in a Century | Unicorn Booty

Pingback: Hundreds Rally in Los Angeles to Stop Oil Trains | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: LA River Revitalization: The Story of Master Plan Gone Awry

Dear Sir,

How I can See the Engineering drawings of all Parts, Structures and Sides Land Scapiny of AI canal in Los Angeles