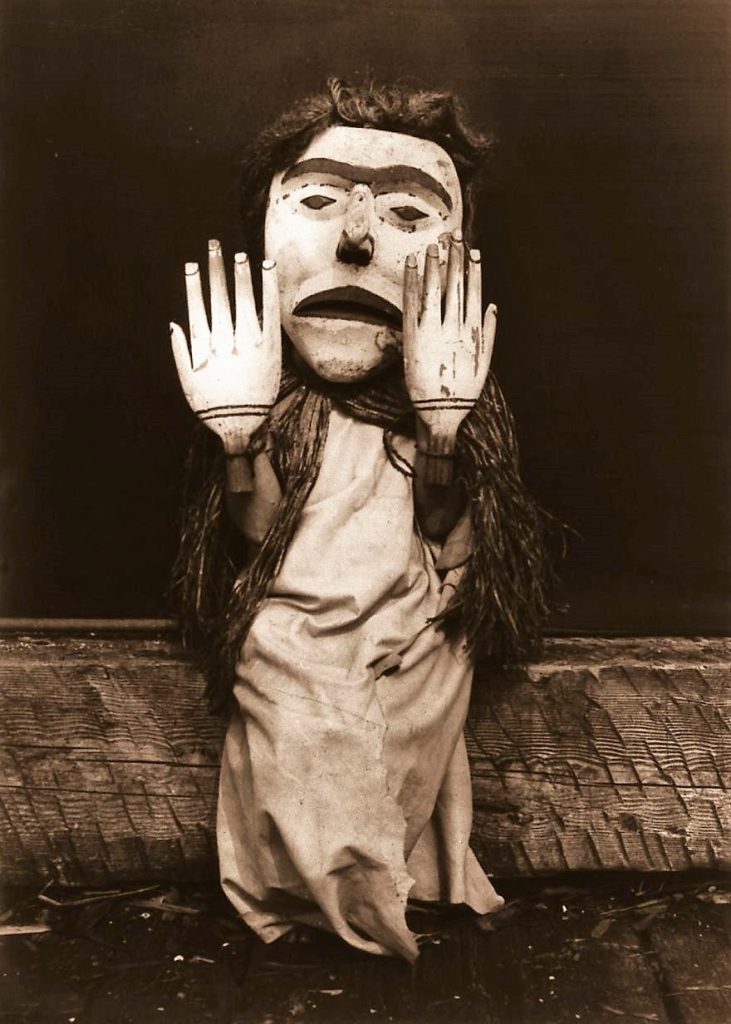

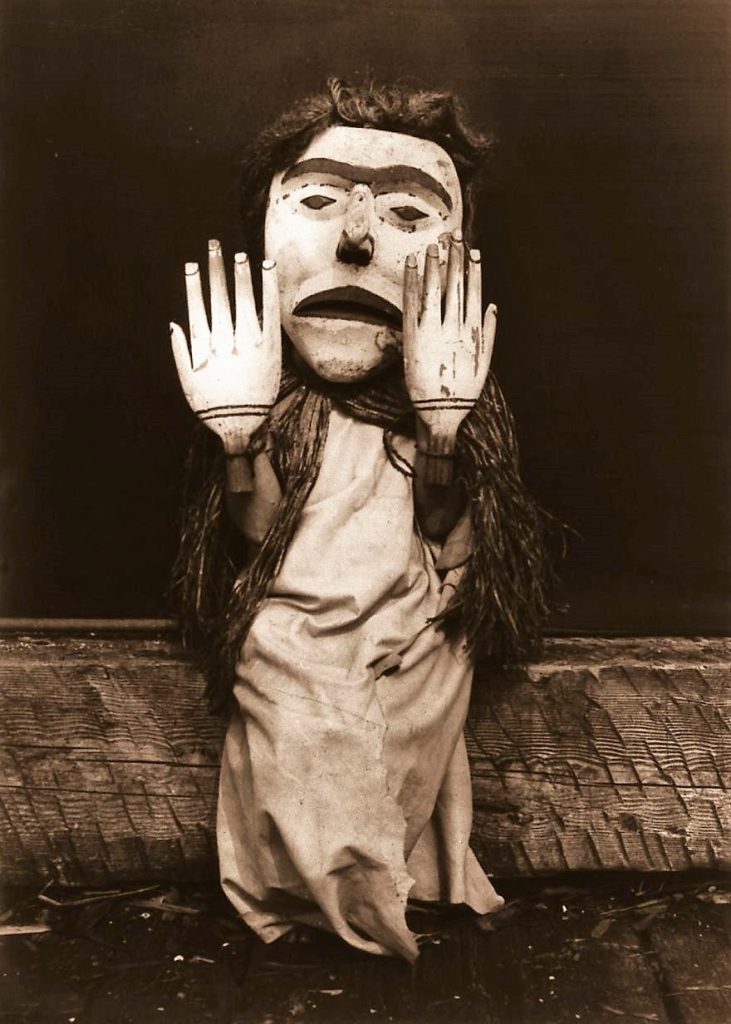

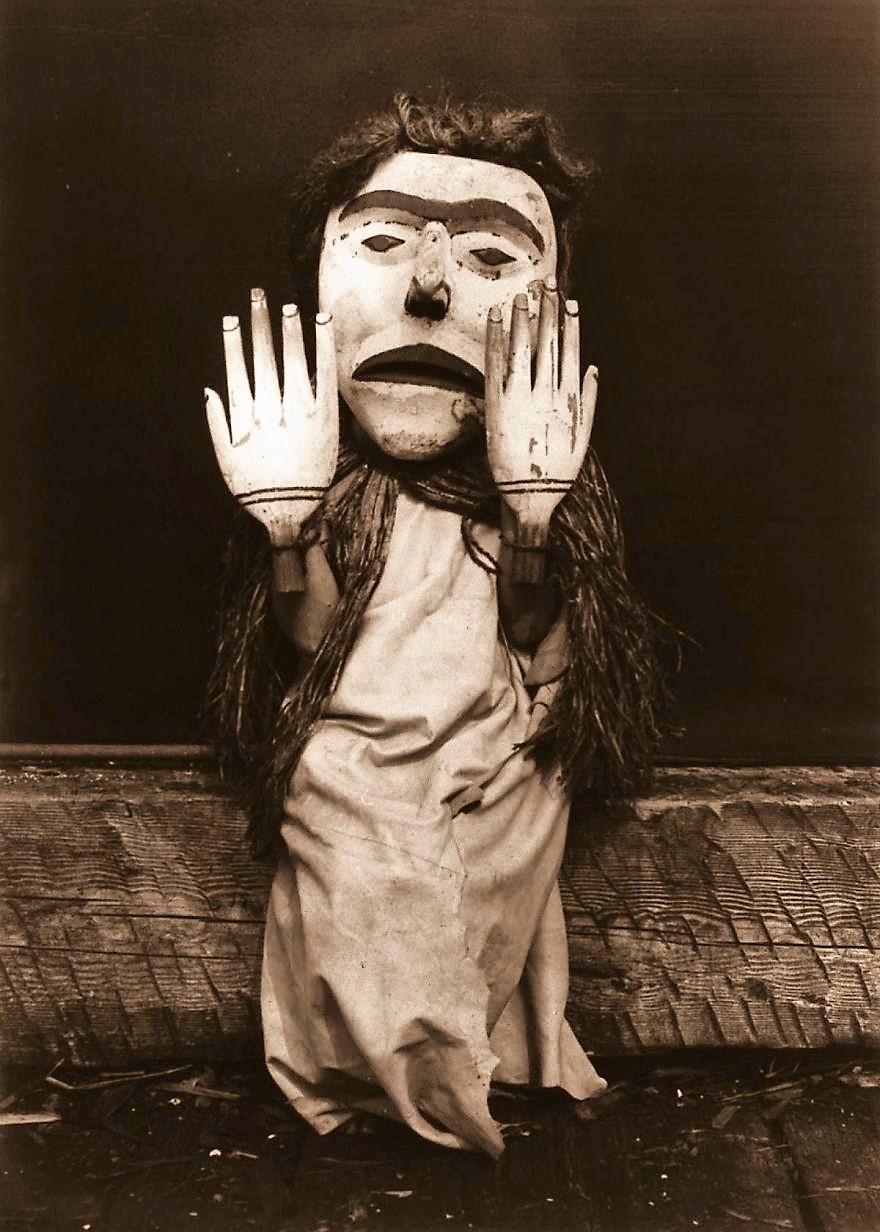

With the Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl Culture) people’s way of life in northern Vancouver Island threatened with genocide, the work of anthropologist Franz Boas and photographer Edward S. Curtis helped protect and preserve the culture at the turn of the 1900s.

Between Exoticism and Cultural Survival

Even as the white European settlers’ diseases, colonization, and forced assimilation destroyed indigenous cultures of the northwest Pacific coast of the US and Canada, some sought to document the ways for science, art, and film. With regard to the Kwakwaka’wakw people of northern Vancouver Island, early 20th Century efforts of German-American anthropologist Franz Boas and famed photographer Edward S. Curtis had the effect of preserving and protecting the ways of a peoples that lost 75 percent of their population at the end of the 19th Century.

Boas called them the Kwakiutl, after a single community in the Fort Rupert area that later became misapplied to mean all the nations who spoke Kwak’wala, as well as three other Indigenous peoples whose language is a part of the Wakashan linguistic group, but whose language is not Kwak’wala. These peoples, incorrectly known as the Northern Kwakiutl, were the Haisla, Wuikinuxv, and Heiltsuk.

Historically, the Kwakwaka’wakw people fished and hunted, and gathered wild fruits and berries. Ornate weaving and woodwork were important crafts, and wealth, defined by slaves and material goods, was prominently displayed and traded at potlatch ceremonies. Boas’ studies found wealth and status were not determined by how much you had, but by how much you had to give away. This act of giving away your wealth was one of the main acts in a potlatch.

It was hoped that the dioramas and the science of anthropology would “teach us a greater tolerance of forms of civilization different from our own, that we should learn to look on foreign races with greater sympathy and with a conviction that, as all races have contributed in the past to cultural progress in one way or another” Franz Boas, The Mind of Primitive Man (1911).

Watch this video on YouTube

On Kwakwaka’wakw culture in a recent European documentary

Mythological History of the Kwakwaka’wakw

Kwakwaka’wakw oral history from Boas’ studies show their ancestors (‘na’mima) came in the forms of animals by way of land, sea, or underground. When one of these ancestral animals arrived at a given spot, it discarded its animal appearance and became human. Animals that figure in these origin myths include the Thunderbird, his brother Kolus, the seagull, orca, grizzly bear, or chief ghost. Some ancestors have human origins and are said to come from distant places.

One Kwakwaka’wakw creation narrative states the world was originated by Raven (Kwekwaxa’we) flying over water, who, finding nowhere to land, decided to create islands by dropping small pebbles into the water. He then created trees and grass, and, after several failed attempts, he made the first man and woman out of wood and clay.

STORY: Myth: The Crow Who Visited the Land of the Seven Cranes

Following is a mythological tale of Raven (Kwekwaxa’we or Great-Inventor), as much a trickster as a creator, related to Franz Boas by a Lau’itsîs informant.

The myth people had nothing to eat. They made a salmon-trap, but no salmon went into it. Then Great-Inventor (Raven) went to the graves, and asked, “Are not there any twins here?” He asked the first grave, which said, “Go to another grave: there are twins there.” Finally he found a grave in which twin girls were buried. He sprinkled one of them with the water of life, and she revived. He said, “I have revived you, because I want you to try to accomplish what I have been working for. Please do help me! I have revived you for this purpose.” Then he married her.

The woman told him to collect some roots of ferns (sâ’laedana). He went out and gathered some. He asked his wife, “What shall I do with those roots?” Then she asked him to strip off the leaves and throw them into the water. She helped him do so. Then she threw them into the water. The leaves covered the whole surface at Ostô’wa, which is situated in the country of the Na’k!wax*daxu, not far from Kingcombe Inlet. Suddenly all the leaves disappeared, the water began to bubble, and salmon were jumping in the river. They went into the salmon-trap. Then the people went down and took out the fish. Deer’s salmon-trap floated away on the water. He had forgotten to make an opening in it. Then the myth people cut the salmon and hung them up to dry.

Now, Great-Inventor went to get fuel to dry his salmon. He went every day. He needed much fuel, because he had so many salmon to dry. When he entered his house, the salmon caught his hair. Then he said, “Let me go! Why do you want to hold me, you who come from the dead?” Then his wife said, “What did you say there?” Great-Inventor replied, “What did I say?” And his wife retorted, “You said, ‘What are you doing, you who come from the dead?'” At once his wife was transformed into foam. The salmon fell down, and all disappeared. Only four salmon remained; and Great-Inventor cried, “No, you do not come from the dead!” But even then the salmon and his wife did not return.

Kanekelak (also spelled Kánekelak, Kanikwi’lakw, Kaniki’lakw, Q!aneqelaku, Q’aneqelakw, Q!â’n?qi’laxu, K’anig yilak’, and other ways): The Transformer figure of Kwakwaka’wakw mythology, who brought balance to the world by using his powers to change people, animals, and the landscape into the forms they have today.

STORY: Mythology of the Crow: Love Trials of the Magic Buffalo Wife

Watch this video on YouTube

The Kwakiutl Culture (Kwakwaka’wakw) dances brought by Chief James Siwid (Seaweed) from New Indians

Many contemporary Kwakiutl identify themselves as Christians but incorporate traditional mythology into their faith, freely blending elements of Christian and indigenous religion. Broadly speaking, Kwakiutl mythology divides the world into several realms: the mortal world, the sky world, the land beneath the sea, and the ghost world (Boas 1935: 125; 1966: 306; Hawthorn 1967: 19; Macnair 1998: 95). In reality, however, it is difficult to discuss Kwakiutl mythology uniformly owing to the diverse accounts found among the many bands that constitute the Kwakiutl First Nations, though some underlying commonalities exist (Joseph 1998: 18-19, Kwakiutl Indian Band 2009; U’mista Cultural Center 2009).

STORY: Cultural Fire: Native Land Management and Regeneration

Watch this video on YouTube

Kwak’waka’wakw Dances (Kwakiutl) from the Central Coast of British Columbia, Canada, 1951

Early Film Captures a Glimpse of Kwakiutl Culture Endangered

In 1914, photographer Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) produced a melodramatic, silent film entitled In the Land of the Head Hunters. This was the first feature-length film to exclusively star Native North Americans (eight years before Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North). An epic story of love and war set before European contact, it featured non-professional actors from Kwakwaka’wakw communities.

Watch this video on YouTube

In the Land of the War Canoes, 1914 silent film fictionalizing the world of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples of the Queen Charlotte Strait region, written and directed by Edward S. Curtis and acted entirely by Kwakwaka’wakw natives.

Rather than documenting Native life in 1914, Head Hunters captured a moment of cultural encounter between Curtis and the Kwakwaka’wakw actors and consultants performing the former’s scripted version of their own past for the camera. On a certain level, Curtis suffered the ailment common to settler colonialists who romanticize the esoteric and exotic aspects of native belief and ritual.

Yet, some aspects of Curtis’ film do have documentary accuracy: the artwork, the ceremonial dances, the clothing, the architecture of the buildings, and the construction of the dugout, or a war canoe reflected Kwakwaka’wakw culture. Other aspects were based on the Kwakwaka’wakw’s orally transmitted traditions or on aspects of other neighboring cultures. The most sensational elements — the head hunting, sorcery, and handling of human remains — reflect much earlier practices that had been long abandoned, but which became central elements in Curtis’s spectacularized tale.

Even more noteworthy than Curtis’s embellishments, though, is the film’s portrayal of actual Kwakwaka’wakw rituals that were prohibited in Canada at the time of filming under the federal Potlatch Prohibition (1884-1951), intended to hasten the assimilation of First Nations. Despite this legislation, the dances and visual art forms—hereditary property of specific families—were maintained through this period and transmitted to subsequent generations, including the performers associated with this project.

An extension of their previous engagement with international expositions, ethnographers, and museums, the film in part helped the Kwakwaka’wakw evade the potlatch ban, maintain their expressive culture, and emerge as actors on the world’s stage. By adapting their traditional ceremonies for Curtis’s film while refusing to play stereotypical “Indians,” the Kwakwaka’wakw played a vital role in the development of the most modern of commercial art forms—the motion picture.

Updated 22 March 2021

Pingback: Ecological Amnesia: Life Without Wild Things | WilderUtopia.com