The Kogi People of Colombia, through two separate documentaries, delivered a message of a sustainable interconnection with nature and community as a way to avert climate and ecological destruction.

What Colombia’s Kogi people can teach us about the environment

By Jini Reddy, Published in The Guardian

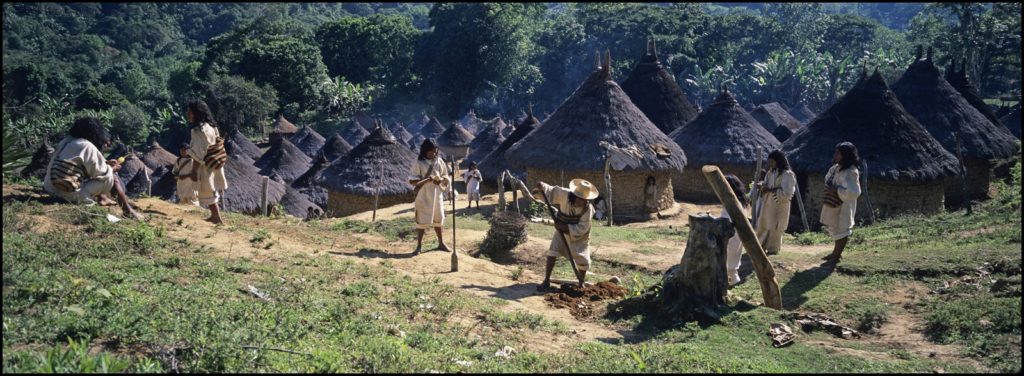

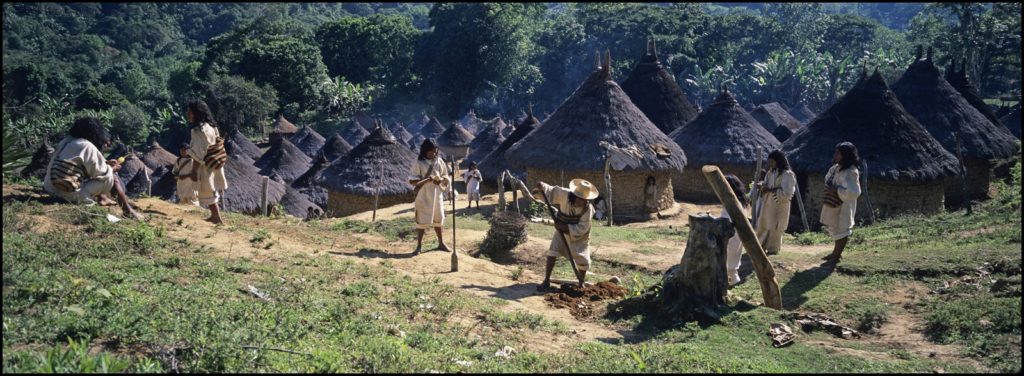

Deep in Colombia’s Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains, surrounded by jungle (and guerrillas, tomb raiders and drug traffickers), live 20,000 indigenous Kogi people. A culturally intact pre-Colombian society, they’ve lived in seclusion since the Spanish conquest 500 years ago. Highly attuned to nature, the Kogi believe they exist to care for the world – a world they fear we are destroying.

In 1990, in a celebrated BBC documentary, the Kogi made contact with the outside world to warn industrialized societies of the potentially catastrophic future facing the planet if we don’t change our ways.

They watched, waited and listened to nature. They witnessed landslides, floods, deforestation, the drying up of lakes and rivers, the stripping bare of mountain tops, the dying of trees. The Sierra Nevada, because of its unique ecological structure, mirrors the rest of the planet – bad news for us.

To this day, the Kogi remain ruled by a ritual priesthood but the training is rather extraordinary. The young acolytes are taken away from their families at the age of three and four, sequestered in a shadowy world of darkness in stone huts at the base of glaciers for 18 years: two nine-year periods deliberately chosen to mimic the nine months of gestation they spend in their natural mother’s womb; now they are metaphorically in the womb of the Great Mother.

And for this entire time, they are acculturated into the values of their society, values that maintain the proposition that their prayers alone maintain the cosmic — or we might say the ecological — balance. And at the end of this amazing initiation, one day they’re suddenly taken out and for the first time in their lives, at the age of 18, they see a sunrise. And in that crystal moment of awareness of first light as the Sun begins to bathe the slopes of the stunningly beautiful landscape, suddenly everything they have learned in the abstract is affirmed in stunning glory. And the priest steps back and says, “You see? It’s really as I’ve told you. It is that beautiful. It is yours to protect.” They call themselves the “elder brothers” and they say we, who are the younger brothers, are the ones responsible for destroying the world. — Wade Davis

STORY: “Embrace of the Serpent” Film: Journey of Healing and Ethnobotany

Watch this video on YouTube

From the Heart of the World – The Elder Brother’s Warning, A Documentary by Alan Ereira, 1990

The Kogi don’t understand why their words went unheeded, why people did not understand that the earth is a living body and if we damage part of it, we damage the whole body. Twenty-three years later they summoned filmmaker Alan Ereira back to their home to renew the message: this time the leaders, the Kogi Mama (the name means enlightened ones [‘sun’ in Kogi, not shamans or curers but respected tribal priests]), set out to show in a visceral way the delicate and critical interconnections that exist between the natural world.

The resulting film, Aluna, takes us into the world of the Kogi. At the heart of the tribe’s belief system is “Aluna” – a kind of cosmic consciousness that is the source of all life and intelligence and the mind inside nature too. “Aluna is something that is thinking and has self-knowledge. It’s self-aware and alive.” says Ereira. “All Indigenous people believe this, historically. It’s absolutely universal.”

The Kogi base their lifestyles on their belief in “Aluna” or “The Great Mother,” their creator figure, whom they believe is the force behind nature. The Kogi understand the Earth to be a living being, and see humanity as its “children.” They say that our actions of exploitation, devastation, and plundering for resources is weakening “The Great Mother” and leading to our destruction.

STORY: Indigenous Legacy: Intergenerational Wisdom for our Times

Many Kogi Mama are raised in darkness for their formative years to learn to connect with this cosmic consciousness and, vitally, to respond to its needs in order to keep the world in balance. “Aluna needs the human mind to participate in the world – because the thing about a human mind is that it’s in a body,” explains Ereira. “Communicating with the cosmic mind is what a human being’s job is as far as the Kogi are concerned.”

The Kogi people believe that when time began the planet’s ‘mother’ laid an invisible black thread linking special sites along the coast, which are, in turn, connected to locations in the mountains. What happens in one specific site is, they say, echoed in another miles away. Keen to illustrate this they devised a plan to lay a gold thread showing the connections that exist between special sites.

They want to show urgently that the damage caused by logging, mining, the building of power stations, roads and the construction of ports along the coast and at the mouths of rivers – in short expressions of global capitalism that result in the destruction of natural resources – affects what happens at the top of the mountain. Once white-capped peaks are now brown and bare, lakes are parched and the trees and vegetation vital to them are withering.

Behind the drab façade of penury, the Kogi lead a rich spiritual life in which the ancient traditions are being kept alive and furnish the individual and his society with guiding values that not only make bearable the arduous conditions of physical survival, but make them appear almost unimportant if measured against the profound spiritual satisfactions offered by religion. … maybe a dance, a song, or some private ritual action that, quite unexpectedly, offers a momentary glimpse into the depths of a very ancient, very elaborate culture. — Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff

“The big thing in coastal development in this area is the ‘mega-projects’, especially the vast expansion of port facilities and associated extensive infrastructure to link new ports to large-scale coal and metals extraction and industrial plant such as aluminum smelters,” says Ereira.

STORY: Colombia: Stunning Indigenous Rock Art from Amazonia

In a poignant scene in the film, CNN footage from September 2006 shows the Kogi walking for miles to protest against the draining of lagoons to make way for the construction of Puerta Brisa, a port to support Colombia’s mining industry.

What happens at the river estuary affects what happens at the source, they say, over and over again. “The Kogi believe that the estuary provides evaporation that becomes deposited at the river source. So if you dry up the estuary you dry up the whole of the river source,” says Ereira.

In the film, the views of the Kogi are backed up by a specialist in ecosystem restoration, a professor of zoology and a world leader in marine biology. “Along this stretch of coastline, you have a microcosm for what is happening in the Caribbean and also on the rest of the planet,” says the latter, Alex Rogers, of Oxford University, on camera. “Their view that all these activities are having an impact at a larger scale are quite right.”

It’s not all doom and gloom: the Kogi end the film on a message of hope: don’t abandon your lives, they say, just protect the rivers. But how to do that? One way forward is to engage the Kogi (and other indigenous communities who have an understanding of environmental impacts) in environmental assessment plans.The Tairona Heritage Trust has also been set up to support projects proposed by the Mamas. But Ereira stresses, “The Mamas are very clear about how we should take notice of what they say. Listen carefully, think, make our own decisions. They don’t want to tell us what to do.”

The central personification of Kogi religion is the Mother-Goddess. It was she who, in the beginning of time, created the cosmic egg, encompassed between the seven points of reference: North, South, East, West, Zenith, Nadir, and Center, and stratified into nine horizontal layers, the nine ‘worlds,’ the fifth and middlemost which is ours. They embody the nine daughters of the Goddess, each one conceived as a certain type of agricultural land, ranging from pale, barren sand to the black and fertile soil that nourishes humankind.

The seven points of reference within which each Cosmos is contained are associated or identified with innumerable mystical beings, animals, plants, minerals, colors, winds, and many abstract concepts, some of them arranged into a scale of values, while others are more of an ambivalent nature. The four cardinal directions are under the control of four mythical culture heroes who are also the ancestors of the primary segments of Kogi society, all four of them Sons of the Mother-Goddess and, similarly, they are associated with certain pairs of animals that exemplify the basic marriage rules. — Reichel-Dolmitoff (1976)

STORY: Hopi Legend: Koyaanisqatsi and World Destruction

Watch this video on YouTube

Trailer for Aluna, a Documentary by the Kogi Mamas themselves, with Alan Ereira

“I would hope that ordinary people will come away from the film feeling empowered to express what they already know – which is that the planet is alive and feels what we do to it,” he says.

“Everybody who is a gardener in this country already has a Kogi relationship to the earth but they don’t necessarily have a language to express that. They have an empathetic relationship to the land and what grows on it, and that empathy is what we have build on.”

For more information visit the Aluna film website.

Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff, “Training for the priesthood among the Kogi of Colombia,” in ENCULTURATION IN LATIN AMERICA: AN ANTHOLOGY, Edited By Johannes Wilbert (Los Angeles, UCLA Latina American Center Publications, 1976), p. 265-288.

H-T: Gregory Schaaf

Updated 3 May, 2021

Pingback: Embrace of the Serpent: Ayahuasca as Society's Healer | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Isolated Kogi Tribe's First Descent Brings a Disturbing Warning to the World - AMOverview