As California continues with massive wind-driven, high-intensity wildfires that often turn deadly, the governmental and institutional response has been to thin forests and “grind up chaparral vegetation” to fight fires. Naomi Pitcairn points to a movement by plant community and wildfire experts led by the Richard Halsey of the Chaparral Institute to focus on protecting vulnerable communities rather than trying to control nature, which now faces extreme heatwaves and droughts from an unpredictable greenhouse-gas-warmed climate.

California’s Misguided Wildfire and Chaparral Response

Chaparral expert and author Fire Chaparral, and Survival in Southern California (2008), Richard Halsey bemoans “The Wrong Focus of Fire Policy,” the title of his May 16th open letter to Jerry Brown regarding the governor’s recent executive order on fire. Halsey represents the Escondido-based research group, the California Chaparral Institute, and his letter, signed by an impressive list of experts, states that: “The basic problem is that the order focuses on forests, many miles away from where wildfires threaten us the most.”

The letter finds the governor’s current “focus on dead trees is especially misguided because all of the wildfires most devastating to communities had nothing to do with such forests.” “And while it is reasonable to remove hazard trees immediately adjacent to roads and homes,” it goes on “it makes no sense to spend millions of dollars to treat entire forests while the actual fire threat facing thousands of families occurs very far away from these forests.“

“We have to look at how we protect lives and property, not how we stop wildfires,” Richard Halsey of the California Chaparral Institute said. “The problem is, we keep doing the same thing, over and over again.” — Santa Barbara Independent

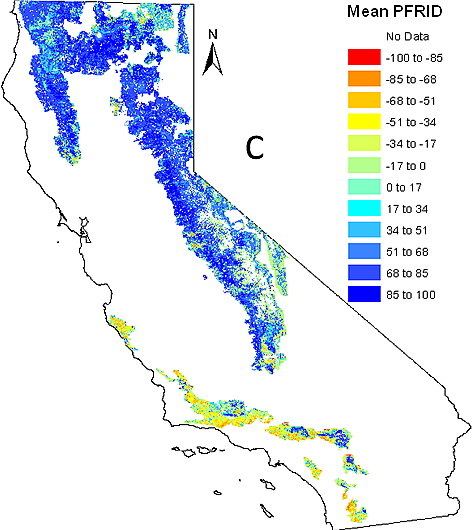

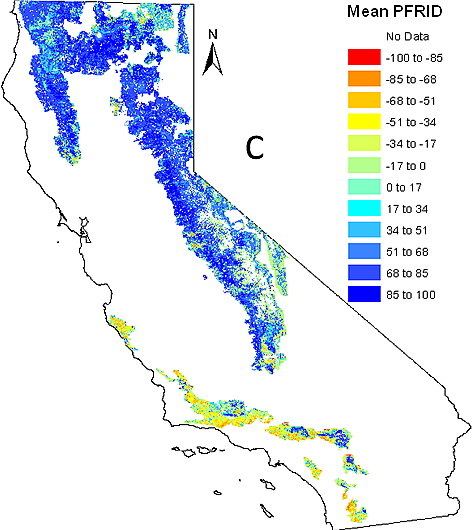

The threat of excessive fire to native shrublands is statewide but is especially extreme in the southern portion. As shown in the map below, most of the plant communities within the four National Forests of southern California are threatened by too much fire (shown in red to yellow colors).

The letter goes on to urge the governor to “break from the conventions that have led to the current crisis and turn California toward a more rational and effective response to the threat of wildfire.” “What we have been doing, trying to control the environment, is not working.”

Most of the 2017 losses in California resulted from “building flammable homes on flammable terrain, not the condition of the natural environment.” “The current approach sees nature as the ‘fuel.’ The focus on fuel has become so powerful that some incorrectly view all of our forests, native shrublands, and even grasslands as ‘overgrown’ tangles ready to ignite, instead of valuable natural resources. As evidenced by the 2017 wildfires, the wildland fuel approach is failing us.” There is a call for the state to take a greater role in regulating development, preventing local agencies from ignoring known wildfire risks “as the city of Santa Rosa ignored with the approval of the Fountaingrove community in the 1990s.”

We must look at the problem from the house outward, rather than from the wildland in. The state must take a larger role in regulating development to prevent local agencies from ignoring known wildfire risks as the city of Santa Rosa ignored with the approval of the Fountaingrove community in the 1990s. The state should support retrofitting homes with proven safety features that reduce flammability – external sprinklers, ember-resistant vents, fire-resistant roofing and siding – and focus vegetation management on the immediate 100 feet surrounding homes.

STORY: Extreme Winds and Wildfires, On Overcoming California Climate Chaos

The state should “support retrofitting homes with proven safety features that reduce flammability – external sprinklers, ember-resistant vents, fire-resistant roofing and siding – and focus on vegetation management in the immediate 100 feet surrounding homes. “ (Indeed, this writer has noticed a lack of information made available by the Ventura County on home retrofitting, and recommends relying of FEMA, when in doubt.)

“We must address the conditions that are actually causing so many lost lives and homes – wind-driven fires and the embers they produce that ignite flammable structures placed in harm’s way.” (Halsey’s bold)

After the 2007 Southern California fires, former San Diego Fire Chief Jeff Bowman and others formed the San Diego Regional Fire Safety Forum, pointing out that there were stacks of fire task force documents from previous decades with “unrealized recommendations” a trend, which according to Jeff Bowman, continues today.

Jon Keely PhD, a research scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey expresses similar frustrations. He laments the policy of treating chaparral like a forest, citing the fact that every chaparral fire is a crown fire. There isn’t that space between the crown and floor that a forest has so that the fuel removal that has some success in forests isn’t effective with chaparral. Dr. Keely also points out that the fuel breaks that were created on ridge tops were not effective in stopping the 2017 fires.

STORY: Yosemite: An Ecosystem Nourished By Wildfire

After investigating why homes burn in wildfires, research scientists Syphard et al. (2012) concluded, “We’re finding that geography is most important – where is the house located and where are houses placed on the landscape.” Buildings on steep slopes, in Santa Ana/sundowner wind corridors, and in low-density developments intermingled with wild lands had the highest probability of burning. “Nearby vegetation was not an important factor in home destruction.” The authors also concluded that “the exotic grasses that often sprout in areas cleared of native habitat like chaparral could be more of a fire hazard than the shrubs. We ironically found that homes that were surrounded mostly by grass actually ended up burning more than homes with higher fuel volumes like shrubs,” Syphard said.

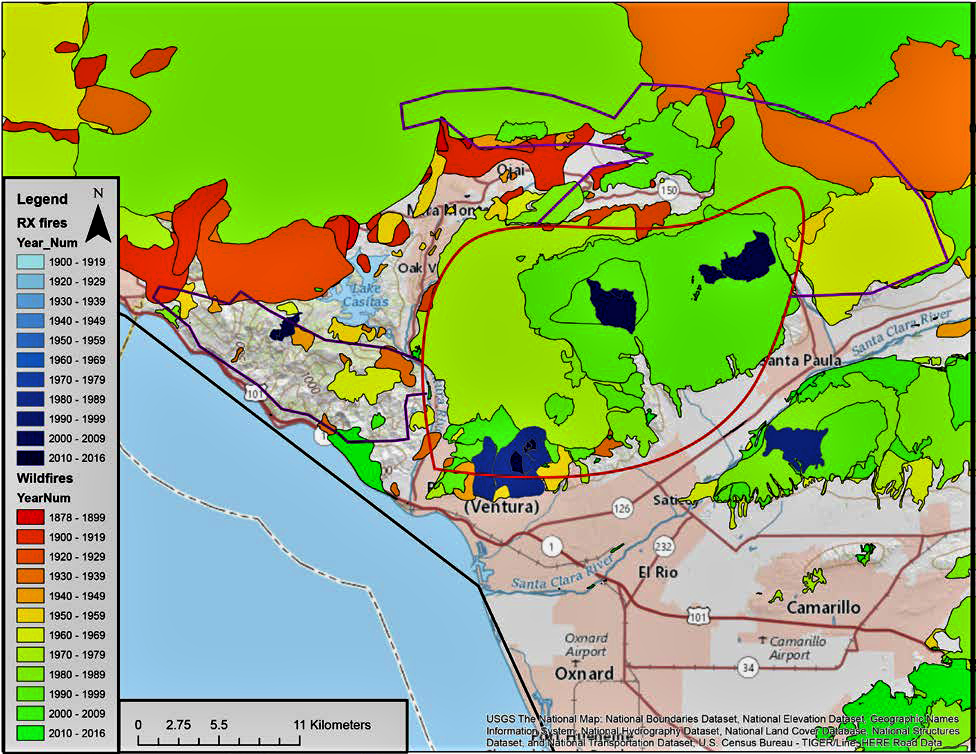

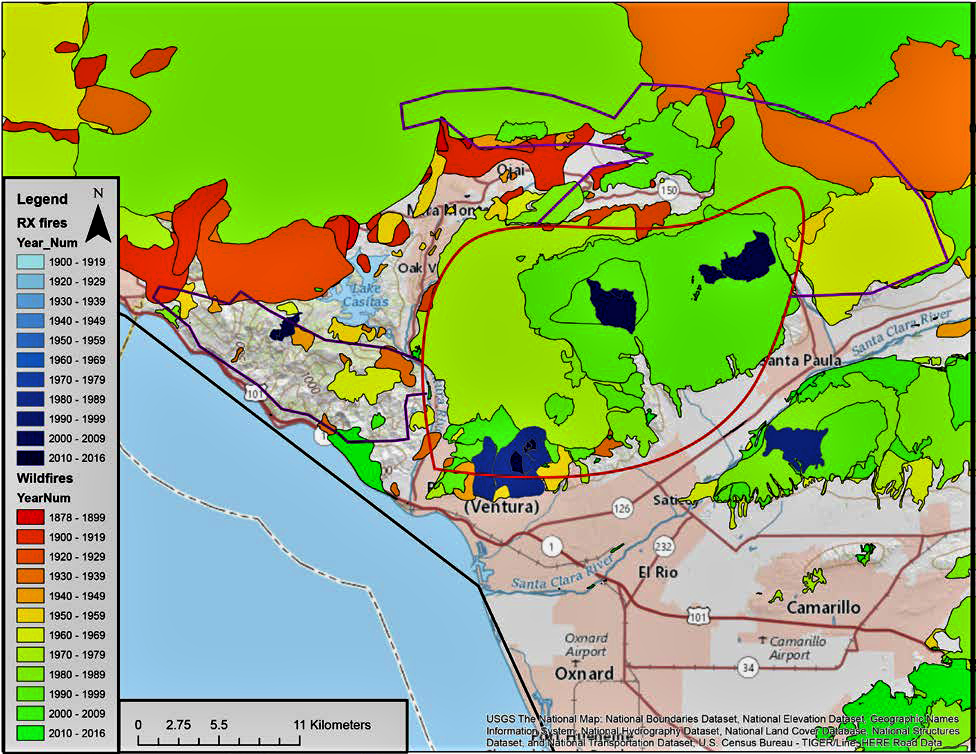

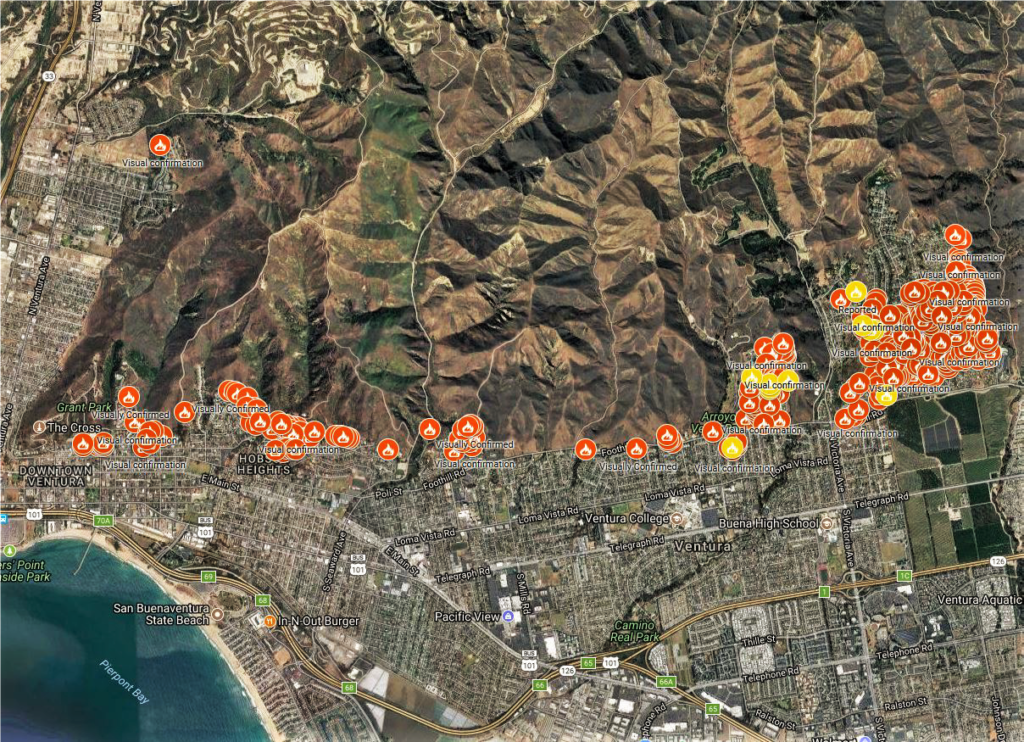

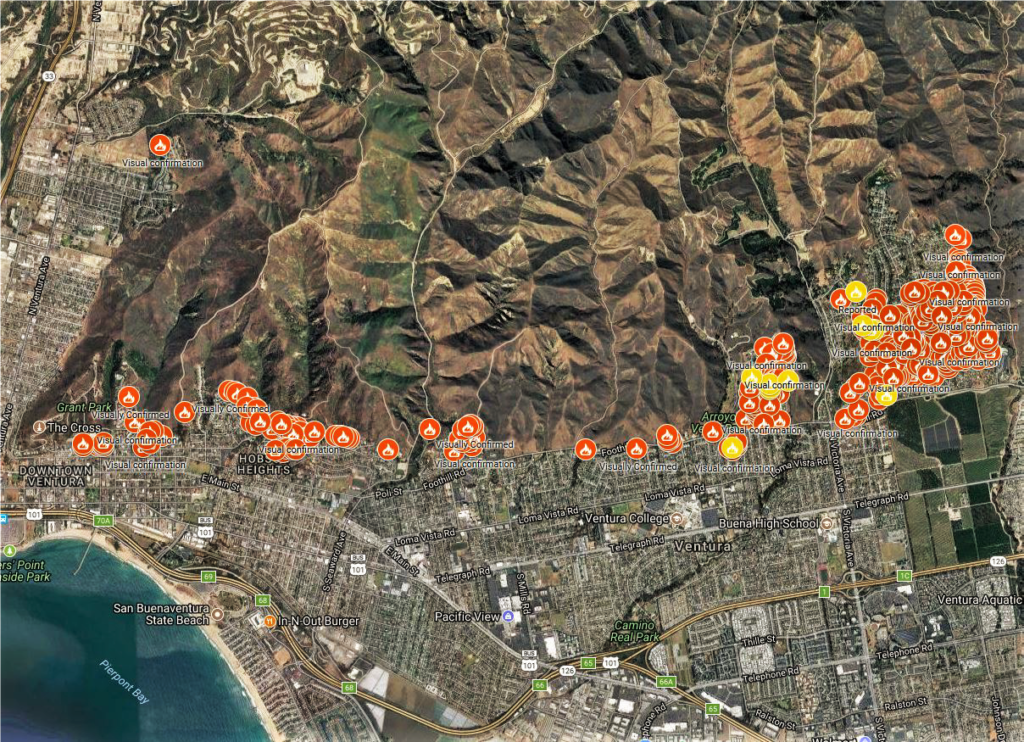

Initially, the Thomas Fire spread 14 miles from its origin outside of Santa Paula to downtown Ventura in about five hours, with spot fires ignited by embers along the entire way. This kind of fire behavior would likely defeat any fuel break.

Further research is needed to determine all the factors involved in the Thomas Fire’s spread, but the consequences are clear from the damage assessment shown in the image below. The prescribed burns did little to protect the community. This is especially the case for the southernmost prescribed burn just above the northern edge of Ventura.

STORY: Protect Greater Yosemite Ecosystem from Salvage Logging

“Creating large areas of clearance with little or no vegetation creates a ‘bowling alley’ for embers. Without the interference of thinned, lightly irrigated vegetation, the house becomes the perfect ember catcher. To make matters worse, when a fire front hits a bare fuel break or clearance area, a shower of embers is often released (Koo et al. 2012).

Rather than “treating” chaparral, the Board of Forestry should develop strategies to protect its further loss.

- Shift the focus to saving lives, property, and natural habitats rather than trying to control wildfires. These are two different goals with two radically different solutions. This new focus can help existing communities withstand wind-driven wildfires, and improve alerts and evacuation procedures and programs, instead of continually pouring resources into modifying a natural environment that continually grows back and will always be subject to wildfire (Moritz et al. 2014).

- Quantify all the risks, statewide. Conduct a comprehensive examination of fire and debris flow hazards across the state. Require the use of fire hazard maps, post-fire debris flow maps, and local expertise to play a significant role in planning/development/zoning decisions. One of the primary objectives in land use planning should be to prevent developers and local planning departments from putting people in harm’s way.

- Start at the structure first when developing local plans to protect homes. Develop action plans in Community Wildfire Protection Plans (CWPPs), similar in scope and detail to those traditionally developed for vegetation treatments, that address the wildfire protection issue from the house outward, rather than from the wildland in. Require that Fire Safe Councils include structure and community retrofits as a significant portion of their activities. This approach has been endorsed by a strong consensus of fire scientists and is illustrated well in this National Fire Protection Association video with Dr. Jack Cohen:

Watch this video on YouTube

- Encourage retrofits. Promote legislation on the state and local level to assist existing neighborhoods-at-risk in retrofitting homes with known safety features (e.g., external sprinklers, ember-resistant vents, replacing flammable roofing and siding with fire-resistant Class A material, etc.). Establish a tax rebate program, similar to the one used to promote the installation of solar panels, to encourage homeowners to install such fire safety features. Provide incentives to roofing companies to develop and provide external sprinkler systems for homes.

- Identify all flammability risks. Create and promote a fire safety checklist that encourages the complete evaluation of a home’s vulnerability to wildfire. Beyond structure flammability, it is imperative that this list cover flammable conditions around the home, such as the presence of dangerous ornamental vegetation, under-eave wooden fences/yard debris, and flammable weeds.

- Help with grants. Promote legislation on the state and local level to assist community Fire Safe Councils in acquiring FEMA pre-disaster grants to assist homeowners in retrofitting their homes to reduce their flammability.

- Comprehensive evacuation plans. Promote the development of clear evacuation/response plans that all communities can understand. Promote programs that will dedicate a regular time each year for communities to practice their evacuation plans.

- Incentives to prevent building in high fire hazard zones. Beyond restricting development in high fire/flood hazard areas, the state could also internalize the costs of fire protection so developers assume the responsibility for possible losses caused by future wildfires and post-fire debris flows. Creating incentives to reduce or prevent development in high fire/flood hazard areas is an achievable goal. The City of Monrovia implemented a creative approach – creating a wider urban-wildland buffer by purchasing parcels in high fire hazard zones. Because the city’s hillside acreage was both publicly and privately owned, the City Council decided to seek voter approval for two measures. The first designated city-owned foothill land as wilderness or recreational space and limited development on the private property. The other was a $10-million bond, the revenues from which would be used to purchase building sites from willing sellers. Both passed by a wide margin. In the end, Monrovia spent $24 million for 1,416 acres, paying off the bonds with parcel taxes and gaining an added benefit: a deeper urban-wildland buffer. (Miller 2018)

- Science-based defensible space guidelines. Expand defensible space guidelines so treatment and distances are based on science and recognize the physical impact of bare ground on ember movement, increased flammability due to the spread of invasive weeds, and increased erosion and sediment movement in watersheds. The research has clearly indicated that defensible space distances beyond 100 feet can be counterproductive.

- Peer-reviewed Vegetation Treatment Program. Require Cal Fire to submit its latest Vegetation Treatment Program Environmental Impact Report (EIR) to an outside, independent, science-based, peer-review process prior to its public release for public comment. Such a review was required by the state legislature for the 2012 version. Require Cal Fire to follow the recommendations offered by the independent review committee in both the EIR’s supporting background information and proposed action plan.

- Establish an interdisciplinary, statewide Fire Preparedness Task Force (FPTF) versed in Catastrophic Risk Management (CRM) to evaluate our response to wildfire hazard. CRM is successful because it helps managers in high-risk organizations make better decisions by reducing their tendency to “normalize deviance,” engendering a focus on p positive data about operations while ignoring contrary data or small signs of trouble. Airlines use CRM to objectively analyze plane crashes, thereby creating safer planes. Without CRM, small deviations from standard operations procedures are often tolerated until disasters, such as the Deepwater Horizon offshore oil platform blow out, the Challenger Space Shuttle explosion, or unprecedented losses caused by the 2017 wildfires expose an organization’s failures. Ensure that a majority of task force members can speak freely, enabling them to offer creative solutions, and that half of the membership is outside the fire profession

- Reduce human-caused ignitions. Since nearly all of California’s devastating wildfires are human-caused, significant resources should be dedicated to reducing such ignitions. One of the objectives of the FPTF should be to develop a statewide action plan, in collaboration with land management agencies, Cal Trans (since many ignitions occur along roads), Cal Fire, and public utilities (since many of the largest fires have been caused by electrical transmission lines), to reduce the potential for human-caused ignitions. The following suggestions should be considered: requiring the underground placement of electrical lines, placement of roadside barriers to reduce vehicle-caused sparks/ignition sources, closure of public lands during periods of extreme fire danger, and increasing the number of enforcement personnel to monitor illegal access, campfire, gun use, etc. on public lands.

Richard Halsey’s San Diego-area-based Chaparral Institute was “established shortly after the 2003 Cedar Fire in San Diego County, the 273,000 acre wildfire that marked the beginning of the California’s new era of catastrophic mega fires.” They advocate for chaparral, and maintain that it was “inaccurately blamed by some as the cause of the fire’s devastation.”

“San Diego County responded to this misperception by proposing a program to clear 300 square miles of backcountry habitat,” they wrote. “After six years of involvement by the Institute and others to help the county develop a new fire risk reduction plan based on science, the county proceeded with their original program. The program was dropped after the Institute successfully challenged it in court. Since 2003, the Institute has produced publications and provided hundreds of public presentations explaining the value of the chaparral ecosystem and how we can live safety within California’s fire-prone environment.”

The Institute has also coined several popular concepts to help promote science-based fire safety and an appreciation for the chaparral including reducing fire risk in our communities “from the house out rather than from the wildland in” and identifying legacy chaparral stands over 60-years-old as “old-growth chaparral.”

Says Halsey: “Chaparral now is more commonly recognized as an important part of California’s natural environment. The US Forest Service has issued a major policy statement recognizing the value and fragility of the chaparral and has held several symposia focusing on the ecosystem services it provides. New publications are also helping the public recognize and appreciate the chaparral.”

Naomi Pitcairn: MFA Parsons School of Design, Design and Technology. BA – NYU. Photographer, writer, prankstress, Chalkupy organizer, artivist, whistleblower supporter.

Updated 26 July 2021

Thank you for writing this. It does an excellent job explaining the main points of our letter. In fact, I even like it better:)

Pingback: Wild Sonoma's 'Valley of the Moon' - Living with the Land | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Rising from the Ashes: Wildfire Resilience for Los Angeles - WilderUtopia