Bone-setters, herbal curanderos, and spiritual guides or shamans provide Highland Mayan traditional healing, with good physical and mental health options for poor Indigenous Guatemalans.

Inside a Maya Healing Ceremony

Excerpt By Samuel Gilbert, Published in Al Jazeera

Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala – At the Cofradia de Conception in Santiago Atitlan, Juan Ramirez, 28, sits pensively on a wooden bench, his outstretched leg held gently by Don Juan Pacach, a Mayan priest and bone-setter.

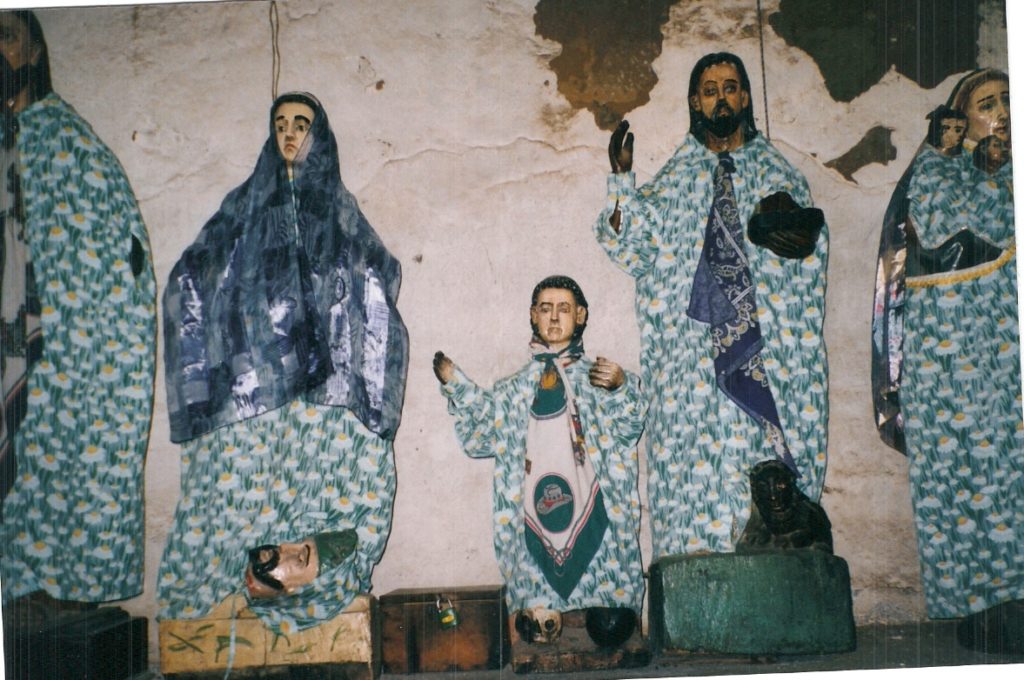

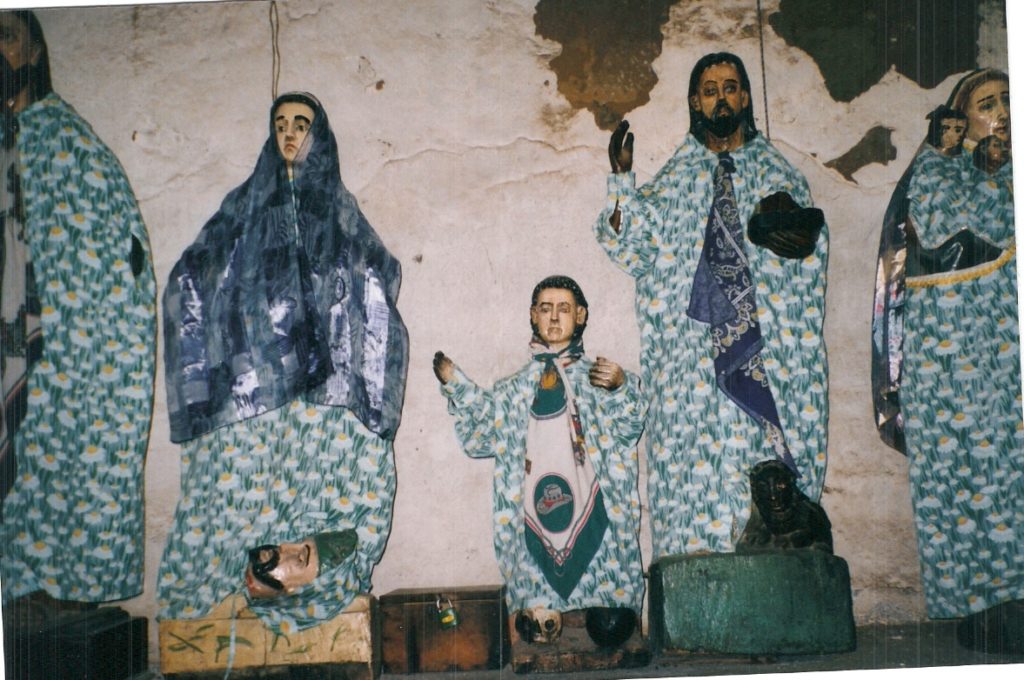

The windowless room – part Catholic shrine, part traditional Mayan healing space – is set back from a narrow unmarked street up a hill in this lakeside Mayan village.

Its interior is lit by thousands of Christmas lights strung across the roof and woven through a menagerie of Catholic saints that surround an altar to Baby Jesus and San Simon/Maximon, the indigenous Mayan folk saint venerated in the Guatemalan highlands.

Minutes before, Ramirez had limped in to receive the second of three treatments for his injured leg. “I have been coming to Don Juan since I was a child,” he says, as the kneeling bonesetter – back-lit by the lights of the shrine – begins gingerly to roll up Ramirez’s trouser leg, revealing an ankle sprain and a large contusion.

Ramirez, a physical education teacher and tuk tuk driver (the prolific three-wheeled taxis that zoom around the steep roads of surrounding Lago Atitlan), injured his leg the week before during a football match. “That sport is often the culprit,” says Don Juan, his hands moving around Ramirez’s injury, assessing the healing progress. “It is much less swollen today,” he concludes.

“These plants have the same energy as we do. They can be used to treat almost anything,” [Christine Gonzales Pop, a Mayan curandera and herbalist from San Pedro Lake Atitlan] says. Christine also makes medical teas, tinctures and packaged herbs for medicinal baths and cleansings. Her treatments are often the only affordable option for her patients. “I want to rescue the tradition,” says Christine, who sees her practice as fulfilling both a dire need in her community as well as countering what she views as the pervasive and often misguided use of synthetic medications.

STORY: Popol Vuh: The Ancient Maya Dawn of Life and Overcoming the Forces of Awe

In his nearly 20 years of bone-setting, Don Juan has treated everything from sprained ankles to dislocated shoulders and severe fractures. His gift, believed to be passed on by ancestors or known intuitively, comes with a deep sense of commitment to the community. “Many cannot afford or do not have access to doctors,” he explains, “So they come to us.”

“If it was broken I would have still come to Don Juan,” Ramirez says. Don Juan has treated him for three previous injuries. “For the bones we go to Don Juan. For illness we see a curandero [folk healer/herbalist]. And for a spiritual problem with see a guia spiritual [spiritual guide or shaman],” Ramirez explains.

Together, these different types of Highland Maya traditional healers comprise a holistic indigenous healthcare practice that provides an indispensable service to the Indigenous poor, who remain critically underserved by the state healthcare system.

“So far as health is concerned, more than half the population have no access to official health services, the most seriously affected being the native population, which is mainly to be found living in rural areas of the country,” writes Dr Hugo Icu Peren, the director general of the Guatemalan Association of Community Health Services.

STORY: Maximón: The Underground Great Grandfather of Western Guatemala

‘This is our Highland Maya tradition’

Reaching into a small bag, Don Juan removes some cloth containing his “material” – a piece of a bone he found in 1979 while working in construction.

“When God created the world he left special items in many places,” he explains.

Each bone setter has their own “material”, which they use to practice their ancient craft.

“This is not something you choose. It is not a career. It is a mission,” he continues, echoing the Mayan belief that some individuals have been granted the gift to heal and that the signs of that calling often begin at birth and continue throughout life.

“My grandmother would always say to me that I was a Mayan priest. But I thought she was joking,” he says.

For years, Don Juan resisted the calling, hiding the bone in his cupboard and ignoring the visions, dreams and even physical illnesses believed to be signs of it. Then, 19 years after he found the bone, a friend and Mayan priest visited his house. Without being told anything, the priest immediately went to the cupboard where Don Juan had put the bone.

He recalls how the priest told him to stop denying his calling and that he needed to carry the bone with him at all times. Then he began to teach him how to cure people. Switching between Spanish (for the benefit of our translator Samuel Botan Sen, a local guide) and Mayan Tz’utujil, Don Juan utters a few quick words as Ramirez bears down in preparation for what is to come.

Using his material, Don Juan begins to deeply massage the leg, focusing on one point and moving outwards with steady, deliberate pressure. Gritting his teeth and clenching the sides of the chair, Ramirez yells out as Don Juan moves over the injured area with a series of methodical movements. “Sometimes it takes two or three men to hold them down,” says Don Juan.

The sessions last three to 10 minutes but are intense. “It’s painful but it works,” says Ramirez, handing Don Juan a single green bill, 20 Guatemalan quetzales, the equivalent of $3.

“The hospital would charge 300-400 Q ($40-$52) and put my leg in cast. But I have to work,” Ramirez says, explaining his reasons for visiting Don Juan – a mix of practicality, tradition and faith. “This is our tradition. I believe in Don Juan. And I trust him completely.”

She carries a wicker basket brimming with bundles of multicolored candles, bottles of Quetzalteca (liquor), rice, sugar, eggs, copal (incense) and a live chicken. She has traveled all the way from Antigua to solicit the skills of Ramon Tzunun, one of six Mayan priests who work out of this shrine to Maximon.

“He is the grandfather, the protector,” says Ramon, motioning to a seated 4ft-tall wooden mannequin dressed in a dapper suit, cowboy hat and sunglasses.

STORY: Maya Ruins at Tikal: A New Beginning at Winter Solstice

Healers of the highlands

At 57, Don Juan is a well respected bone setter around Lago Atitlan, the spiritual center of the highlands and the region with the greatest concentration of indigenous healers. Many patients come from the rural hinterlands to seek treatment from the various types of traditional healers here whose legitimacy, according to Icu Peren, “is rooted in the trust placed in them by indigenous families.”

The Mayan holistic healing tradition is a medico-religious one — viewing the ailments of the body and the spirit as fundamentally interconnected. “Mayan traditional healing is a complex blend of mind, body, religion, ritual and science,” writes Marianna Appel Kunow, in her book Maya Medicine.

The healing practice is also rooted in a deep sense of service to the Mayan people.

Read the entire article at Al Jazeera.

H-T: Matt Pallamary

Pingback: Volcanoes and Vibrant Colors of Antigua Guatemala | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Spirit Talk: Stories of Traditional Healers of Central Australia