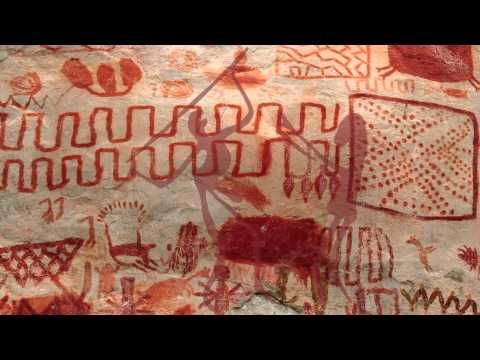

Prehistoric rock art paintings on vertical rock faces in an Amazonian wilderness in Colombia were recently photographed and filmed for western eyes, with commentary from Dalya Alberge (Guardian) and Mark Plotkin (Amazon Conservation Team). The pretense of this British filmmaker as the “discoverer” of the paintings is of course ludicrous. The once populous Karijona Tribe most likely painted these masterpieces, and continue to live uncontacted in the vast rainforest, and anthropologists and explorers have studied the region for hundreds of years.

World’s most inaccessible rock art publicized in the heart of the Colombia jungle

By Dalya Alberge, Published in The Observer

A British wildlife film-maker has returned from one of the most inaccessible parts of the world with extraordinary footage of ancient rock art.

In an area of Colombia so vast and remote that contact has still not been made with some tribes thought to live there, Mike Slee used a helicopter to access the site and film hundreds of paintings depicting hunters and animals believed to have been created thousands of years ago. He said: “We had crews all over the place and helicopters filming all over Colombia. As a photographer, Francisco Forero Bonell discovered and took the pictures for my movie.”

In 2013, Colombia expanded Chiribiquete National Park from 5,019 square miles (13,000 square kilometers) to more than 10,425 square miles (27,000 square kilometers), making it larger than the state of Massachusetts and one of the largest rainforest reserves in the world. Chiribiquete is honeycombed with tepuys — often dubbed “Lost World” mountains — as well as giant granitic domes, waterfalls, rapids, canyons, caves and unspoiled rivers.

More than simply a vast geography, Chiribiquete is home to many strange and wonderful species: a unique hummingbird, many endemic species of plants and flourishing populations of mammal species which have been decimated or extinguished in other parts of the Amazon. Research just south of the park by New York Botanical Garden scientists turned up a species of tree from the Dipterocarpaceae family that was previously believed to only occur in Africa and Asia. And researchers have yet to conduct thorough scientific investigations in the vast majority of the unknown forests of Chiribiquete. — Mark Plotkin, Amazon Conservation Team

The extraordinary art includes images of jaguar, crocodiles and deer. They are painted in red, on vertical rock faces in Chiribiquete National Park, a 12,000 square kilometer UNESCO world heritage site that is largely unexplored. There are also paintings of warriors or hunters dancing or celebrating. “It is the land that time forgot,” Slee told the Observer.

STORY: Lost White City “Discovered” in Honduran Jungle?

Watch this video on YouTube

Parque Nacional Natural Chiribiquete, producido por la dirección territorial amazonía de Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia 2013.

From Mark Plotkin: A member of a boundary commission sent to the region in 1911 was so captivated by the sheer majesty of the landscape that he wrote of the Ajaju River that runs through Chiribiquete:

“[It] is a beautiful river and different from all the others of the region. Its curves are majestic, and from each one arises enormous and fantastic rock formations that resemble ruins of feudal castles or enormous statues carved by the Cyclops but beginning to deteriorate with the passing of the ages.”

The Colombian geographer Camilo Dominguez recorded similar impressions:

“Small table mountains divided like a chess board that has cracked into different sections and, finally, a whole range of fantastic figures that make this the most breathtaking landscape in the Amazon.”

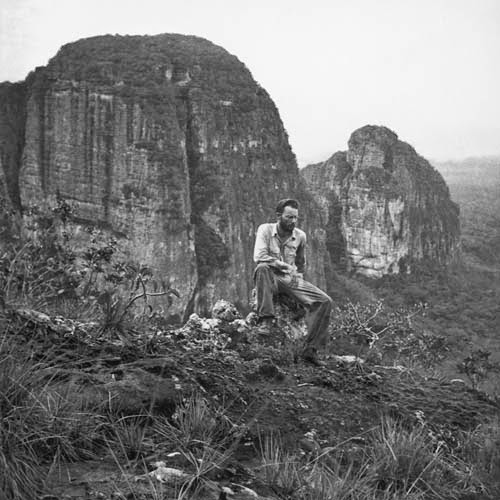

The great ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes carried out the first botanical collections of Chiribiquete in May of 1943. Even the sober-minded Schultes was gripped by the bizarre and beautiful landscape:

“…the isolated quartzitic mountains of [Chiribiquete] are sentinels of a mysterious past. The Cerro de la Campana is one of the westernmost vestiges of these hills and is so strikingly awesome that it is wrapped in legend in the Indian mind….”

More than a half century after he climbed Cerro Chiribiquete, Schultes remained deeply affected by his encounter with these mountains and this rainforest. He kept a magnificent photograph he had taken of Chiribiquete over his desk at Harvard as a constant reminder of this enchanted land. And he told his student and future biographer Wade Davis that these eerie rock formations seemed like giant sculptures left over from God’s workshop: “It was from these first tentative experiments,” Schultes mused, “that He had gone out and built a world.”

There had previously been only vague reports of rock art in the area and a film shot in 2013 (above), which is known as Cerro Campana, he said: “There’s no information, maps or communication. It’s such a massive central part of Colombia.” Though some paintings had previously been found and photographed elsewhere in Chiribiquete, this Cerro Campana art has never been filmed or photographed for public display around the world, according to Slee: “It was an absolutely stunning moment to be able to get the footage.”

From Mark Plotkin: Aside from this august geography, Chiribiquete also features other stunning wonders: the greatest assemblage of pre-Columbian paintings in all of Amazonia, containing hundreds of thousands of depictions of people, animals, shamans, hunters and dancers. Such is the magnitude, realism and beauty of these creations that Castaño reports that he nearly fainted when he first saw them up close. The late Thomas van der Hammen, a Dutch Colombian biologist was so struck by the illustrations that he termed Chiribiquete “the Sistine Chapel of the Amazon.”

Research led by Castaño and van der Hammen in the early 1990s found as many as 8,000 paintings on a single wall. Archaeological dating methods at the time were much less sophisticated than today, and estimates are that the art was created at least hundreds of years ago, and possibly as far back as 18,000 BCE. Conflict with Colombian guerillas brought a halt to research in the mid-1990s, and only recently have scientists been able to return. Still, the art of Chiribiquete still holds many mysteries. Its sheer beauty and spiritual import, though, is without question.

Slee used a helicopter to gain access to the area, as the terrain is impenetrable – thick vegetation, forested rock peaks and valleys, sheer cliffs and giant rock towers soaring through a rainforest canopy.

Professor Fernando Urbina, a rock art specialist from the National University of Colombia, was struck by the “magnificent naturalism” of the depictions of deer when shown the photographs.

STORY: Chumash Sky and Earth Deities and Cosmological Rock Art

“They reveal the hand of a master of painting,” he said, adding that the paintings could be up to 20,000 years old. He was particularly interested in a human figure in a seated position whose arms appear to be folded over his shoulders, a ritual position in Amazonian cultures. “A seated man has special significance as the sage of the tribe,” he said.

The art may have been painted by the Karijona tribe, a few of whose members still live in the region. The seated position might suggest a prisoner or slave, Urbina said. Jean Clottes, a French prehistorian, and author of Cave Art – a book covering key sites such as Lascaux in France – described the images as exciting and well-preserved, but said it would be hard to determine their age because radiocarbon dating could not be used, as they were painted with mineral-based materials derived from iron oxide rather than the charcoal used in European rock art.

From Mark Plotkin: No one has inhabited these sites for many, many years. The Colombia Amazonian rock art Picassos who painted these masterpieces are believed to have been members of the Karijona tribe, a once fierce and populous group. A Spanish soldier who visited the region in the 1790s estimated a population of about 15,000 Karijonas. Introduced diseases in the 19th century decreased the numbers of Karijonas to around 10,000. The turn of the 20th century brought the evils of the rubber boom when groups like the infamous Casa Arana killed, enslaved and mutilated thousands of Karijonas and other neighboring tribes. According to Franco, who consults with the Amazon Conservation Team, by 1920 the Karijonas had dwindled to around 1,000, and today — sadly — only 60 remain.

The species depicted are thought to include capybaras, snakes and anteaters. Slee described the art as a wildlife chapel. “The peoples who once lived here have left in pictures testimony of their awe and respect for the wild,” he said. “When I saw the images, I honestly felt an affinity with the artists. They were attempting to capture the power, grace, spirit and essence of the animal in pictures. Perhaps it was to make the hunt better next day, but there is clearly careful observation in their art. It’s what contemporary photographers, painters, film-makers set out to do when they create a wildlife project.”

From Mark Plotkin: Here again, Chiribiquete may be hiding secrets: Research flights over the region have revealed the presence of one, and as many as three, isolated Indian tribes. In the past, South American governments would contact and acculturate isolated Indian tribes, claiming they were helping the Indians integrate successfully into the outside world. All too often, this contact resulted in cultural disintegration and sometimes outright extinction. The Colombian government recently passed a law — decree 4633 — making it illegal to contact isolated peoples or to destroy their environment. Roberto Franco surmises that one of these “lost tribes” in Chiribiquete is comprised of Karijonas living a traditional lifestyle.

There exist several detailed accounts of what these early Karijonas were like and how they lived. These Indians were noted for, among other things, rowing their canoes while standing, wrapping their chests and abdomens in beaded belts, and piercing their nasal septum with animal bones. And a paper by a German expert on Karijona culture and history wrote: “none of the extensive reports on the Karijonas fail to mention they were cannibals and that for this reason they were continually at war with the neighboring Witoto….”

I met an old Karijona once who was living in the little village of Cordoba on the Caquetá River, far from his original homeland of Chiribiquete. One of the 60 Karijonas remaining from the group decimated by diseases and the rubber boom, he was a wonderful old man, a great storyteller and a boon companion. He told me that Chiribiquete was the heart and soul of the Karijona culture, and that he wanted to visit one more time before he died. He fervently believed there were Karijonas still living in the rainforests of Chiribiquete. I asked him if they would be fierce people, and he replied:

“In the old days, we fought and killed many whites from the rubber company. But, more than the whites, we killed Witotos who were our traditional enemies. We used to be cannibals, you know, so those who would defile Chiribiquete should be warned!”

Chiribiquete has 300 species of birds, 72 of beetles, 313 butterflies, 7 primates, three otters, four cats, 48 bats, eight rodents, two dolphins and 60 fish. Photo from Cromos.

Slee made his name making natural history films and directed the movie Bugs! 3D, about two rainforest insects, narrated by Judi Dench. In 2012, the Observer reported that his Flight of the Butterflies 3D had captured butterflies in unprecedented detail, moving scientists to tears at an early screening. Over the past three years, Slee has been exploring Colombia to make Colombia: Wild Magic, which will be in cinemas next year. Through spectacular footage, it portrays “a majestic tropical wilderness” – but one he said was threatened by humans who are “taking more than they are giving”. With swooping aerial footage and detailed close-ups, it reveals a landscape of canyons and caves, lakes and lagoons, rivers and rock masses with “the largest varieties of living things on the planet”, including unique species of hummingbird and endangered jaguar.

Drawing on the expertise of a dozen scientific advisers, the film warns of threats from the world’s “craving” for natural resources such as gold and emeralds. Slee said: “We’ve got illegal gold-mining polluting the rivers, we’re overfishing the seas, the habitat destruction is massive. We’re taking out the rainforest, we’re losing species every week. We have the most beautiful country on Earth and we are in danger of destroying it. There are places that no Colombian has been. It’s mainly because, when you think of Colombia, you think of kidnapping and drugs.”

Bonell, a Colombian conservationist and photographer, was inspired to become executive producer of the film, describing the region as “one of the few areas on our planet that still remains unspoiled and unexplored.”

The film has been produced by British company Off The Fence, and will be distributed free in schools in Colombia, as well as cinemas, “spreading the word about what their country has and the need to protect it,” Slee said. Slee hopes to return for another large-scale expedition focusing on the rock art. “We’ve probably only scratched the surface,” he said. “There are believed to be many hundreds of these cave paintings dotted throughout that central region.”

References

Basso, Ellen B. Carib-speaking Indians: Culture, Society, and Language. Tucson: University of Arizona, 1977. Print.

Davis, Wade. One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996. Print.

Dominguez, Camilo. “El Rio Apaporis: Vision Anthropo-Geographica.” Revista Colombiana De Anthropologia 18 (n.d.): 129-75. Print.

Franco, Roberto. Cariba Malo: Episodios De Resistencia De Un Pueblo Indi?gena Aislado Del Amazonas. Bogota: Universidad Nacional De Colombia, 2012. Print.

Franco, Roberto. Los Carijonas De Chiribiquete. Bogota: Fundacion Puerto Rastrojo, 2002. Print.

“Los Rostros Detras De Amliacion Del Chiribiquete.” El Espectador. N.p., 20 Aug. 2013. Web. 19 Sept. 2013. <http://www.elespectador.com/noticias/medio-ambiente/los-rostros-detras-de-ampliacion-del-chiribiquete-articulo-441203>.

Schindler, Helmut. “Carijona and Manakini.” Carib-speaking Indians: Culture, Society, and Language. Tucson: University of Arizona, 1977. 66-75. Print.

Schultes, Richard Evans. Where the Gods Reign: Plants and Peoples of the Colombian Amazon. Oracle, AZ: Synergetic, 1988. Print.

Pingback: "Embrace of the Serpent" Film: Ethnobotany as Society's Healer | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Papua New Guinea: Sepik River Initiation and the Crocodile Cult

Pingback: Kogi People’s Lesson From the Heart of the Mountain

Pingback: Ghost Towns and Geoglyphs: Exploring Chile's Atacama Desert - WilderUtopia