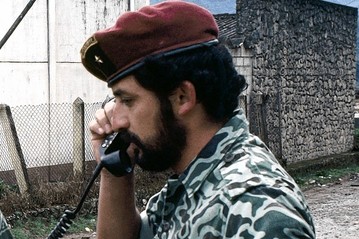

Otto Pérez Molina, a former general in charge of the Nebaj, El Quiche, military base during Guatemala’s genocide from mid-1982 to mid-1983, won the presidency in 2011 only to resign for charges of corruption in 2015. This article was written upon his election.

Adapted from articles by Annie Bird in Rights Action and Nicholas Casey in The Wall Street Journal

As evidence grows of Pérez Molina’s participation in crimes against humanity and genocide, how will the international community respond to this head of State? He is accused of intellectually and materially authoring torture, disappearances, executions, and massacres. As of yet, no State or public official in Guatemala and beyond has publicly discussed the issue of the war crimes and genocide charges against Pérez Molina.

See Related: Allan Nairn Exposes Role of U.S. and New Guatemalan President in Indigenous Massacres – Democracy Now

Electoral authorities reported that Pérez Molina finished with 56% of the vote; Manuel Baldizon finished with 44%, in the November 6th run-off elections. Pérez Molina will take office the first week of January. The U.S. embassy released a statement congratulating him.

Guatemala continues to be a fundamentally undemocratic country, wherein political institutions and the rule of law are corrupted and/or dominated by the traditional powerful elite sectors. Rights Action believes that, in many ways, the “elections” themselves serve to cover-up the underlying lack of democracy and rule of law.

Head of State Accused of Genocide and Other Crimes Against Humanity

Most of the accused crimes General Otto Pérez Molina occurred before the existence of the International Criminal Court, created to try war criminals, making prosecution difficult. However, international law establishes nations have responsibility to prosecute grave human rights abuses – including war crimes and genocide – and no prescription period for their prosecution exists.

Genocide in the Mayan Ixil Triangle.

The 50,000 population of the highland town called Nebaj is still mostly indigenous, Ixil speaking, with many living in severe poverty. Once caught in the crossfire of a right-wing military dictatorship aiming at a band of Marxist guerrillas, Pérez directed the fight against rebels there for two years during Guatemala’s 36-year civil war that left an estimated 200,000 dead. Many assert towns such as Nebaj were deliberately targeted for terror by successive repressive regimes in the 70s and 80s using the pretext of a minor guerrilla movement to murder thousands. Three decades ago, the church in the central plaza was taken over by the military, its bell towers turned into lookout towers. The former nunnery housed Mr. Pérez and his men.

Exhumations continue to unearth loved ones today, more than 600 in the area, who long ago disappeared in the war. They include both villagers and guerrillas. The offensives in Nebaj and the Ixil region almost completely destroyed the twenty-six villages and 145 hamlets existing in 1980 (CITGUA: 1989). It is estimated that this zone produced 80 per cent of the internally displaced between 1981 and 1982 (AVANCSO: 1992), though only a portion of this could be attributed to Pérez Molina’s oversight in 1982.

A truth commission set up by the United Nations later called the killings “acts of genocide against groups of Mayan people.” A Spanish National Court is investigating genocide in Guatemala and the role of Pérez Molina, using the principle of universal jurisdiction. The court has received testimony concerning Pérez Molina’s military ranking and concerning his participation in war crimes.

httpvh://youtu.be/IEN9OBmLdcE

This video contains disturbing images, including shots of Mr. Perez Molina in charge of Nebaj in 1982.

Guerrilla Commander Efraín Bámaca.

During a March 1992 skirmish in the jungle region of the Peten, rebel fighter Efraín Bámaca went missing and the military reported him killed by soldiers. The Guatemalan Attorney General’s office has opened an investigation into Mr. Bámaca’s death and the role of Pérez Molina who was head of military intelligence at the time. Mr. Bámaca’s wife, Jennifer Harbury, an attorney and US citizen, waged a campaign for answers, prompting a release of declassified US intelligence reports suggesting the Guatemalan army placed another body in Mr. Bámaca’s grave, while authorities interrogated Mr. Bámaca in a detention center.

During an August 1993 exhumation of Mr. Bámaca’s grave, a forensics team concluded the body was not Mr. Bámaca. A pentagon cable from July 1995 provides the only on-the record account from the Guatemalan military that connects Mr. Pérez to the case. After Mr. Bámaca’s capture, the military had been “using him as a guide to search for hidden weapons caches.” After the patrol was attacked, “The decision was then made to eliminate Bámaca.” Mr. Perez arrived by helicopter to pick up Bámaca and he was not seen again.” It was further stated that Pérez Molina “ordered officers under his command at the directorate of intelligence of the army” to “physically disappear Bámaca.”

Jennifer Harbury initiated a case in March 2011 against Pérez Molina after Guatemalan courts violated due process and the right to access to justice in an earlier complaint initiated against lower ranking officers who had been under the latter’s command.

CIA Torture Payroll.

Otto Perez Molina was reported to be on the CIA payroll when, as head of the military’s G2 intelligence unit, he allegedly ran a secret torture center on the Mariscal Zavala military base.

In September 2011, a complaint (a formal Allegation Letter) was submitted to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture calling for an investigation into the role that Perez Molina played in the commission of genocide, torture and disappearances in Guatemala during the worst years of State repression and terrorism in the 1980s.

Genocide Denial

Perez Molina has denied not only participation in war crimes, but has also publicly claimed that genocide did not occur in Guatemala.

In 1999, the UN released its Truth Commission report (Memory of Silence) concluding that over 93% of the atrocities during the country’s 36-year civil war were carried out by the military, police and paramilitaries; that the military conducted genocide against the Mayan population in certain areas, including the Nebaj region where Perez Molina was a high ranking officer; that at least 200,000 people were killed, over 45,000 people disappeared, more than 600 massacres were committed and that over 1,000,000 people were forcibly displaced from their homes.

In April 2008, the Catholic Church released its own report (Recovery of the Historic Memory) detailing decades of State repression and terrorism against the mainly indigenous Mayan people of Guatemala . The night following the release of the Church report, the person in charge of the investigation, Bishop Juan Gerardi, was bludgeoned to death, and his body left for all to see. While two former military officers are serving sentences for the assassination of Gerardi, investigators claim that evidence points to Perez Molina’s involvement in the Gerardi killing, placing Perez Molina at the scene of the crime on the night of the killing.

Political Campaign Focused on “Security” and “Justice”

With narcotics traffickers spilling south from Mexico and homicide rates skyrocketing, Guatemalan voters, a fraction of the actual population, have decided to turn back to the military to gain control of the continuing instability. Hence, the central theme in the elections was security and justice. Guatemala’s homicide rate in March 2011 was reported to be 42 murders per 100,000 residents. Guatemala – like neighbors El Salvador and Honduras – has among the highest murder rates in the world, though Honduras’ murder rate is currently double Guatemala’s. This violence is attributable to Guatemala’s historic and structural inequality, repression and impunity in general, and more recently to organized crime, particularly the drug trade.

Escalating drug violence has drawn US attention with the State Department pledging $300 million to fight Central American drug traffickers. Mr. Perez has said during candidate debates he would welcome US troops to battle drug gangs in the country, which Mexico has never allowed. The law-and-order slogan of “La Mano Dura,” the Firm Hand, has resonated in a country with a homicide rate eight times the US. In May, 27 people were found beheaded on a secluded ranch, the work of Mexico’s Zetas gang.

Recent War Crimes Prosecutions

Guatemala’s first female Attorney General, Claudia Paz, has become something of a celebrity for the effective prosecutions she has led against both organized crime kingpins and those accused of crimes against humanity in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. She took office again in 2010 after a recently named Attorney General was fired following scandals that associated him with organized crime.

During her latest time in office, two top organized crime kingpins have been arrested, after they had operated for decades with the protection and involvement of some military, political and legal authorities. A slew of war crimes have started to move ahead (slowly) in a way never seen before.

A former head of the national police was arrested, tried and convicted in July 2011 for the war crime of forced disappearance. Military officers involved in the gruesome (and typical) Dos Erres massacre received extended sentences. On June 20, 2011, former General Hector Mario Lopez Fuentes was arrested as an intellectual author of genocide against the Ixil people, in the Nebaj region, between 1981 and 1982. On October 12, 2011, Jose Mauricio Rodriguez Sanchez, head of military intelligence accused of genocide against the Ixil people, was arrested. Former military Head of State from 1983 to 1985, 70-year-old Oscar Mejia Victores, is now in a military hospital under evaluation for his ability to stand trial. He is also accused in the Ixil genocide.

As these genocide trials advance (almost 30 years later) against the highest ranking officers accused of genocide in the Mayan Ixil region, the circle closes in around Perez Molina, who was also a high ranking officer in the Ixil region at that time.

Fire the Attorney General?

A frequent question during the elections was who would let the attorney general stay on, and both candidates promised to keep her on. However, growing reaction against the prosecution of former military officers, by former military officers, has lead to concern over repression against lawyers and human rights defenders, and concern that the Attorney General will be replaced with someone who continues the longstanding tradition of impunity—illegally blocking prosecutions of both war criminals and organized crime figures.

Ever since the “Peace Accords” of 1996, the growing organized crime networks that generate violence and terror in Guatemala have been directly and indirectly linked to military and former military personnel, particularly military intelligence officers, as well as to people working in the institutions of the State and legal system.

The Attorney General’s office has expressed their intention to continue prosecutions and enjoys the political and financial support of the international community; however, signs of pressure and manipulation within Guatemala are already appearing.

On November 2, 2011, a former military colonel submitted a complaint against 26 well-known figures, including leading human rights advocates, academics, and politicians. Some of those named in this complaint are recognized as former members of revolutionary movements. He accuses them of participating in his kidnapping when he was a university student, while his father served as the Minister of Governance during the regime of Efrain Rios Montt, another former military dictator and intellectual author of Guatemala ’s genocide.

Named in this complaint are two cousins of the current Attorney General, one of whom is deceased and the other who has publicly denied any association with the incident, explaining she was in exile at the time and that the motivation for her inclusion in the list was clearly due to her family ties to the Attorney General.

Continuing with the Violence of the 1980s. With the help of the United States

The election of Perez Molina as president, just as Guatemala was making its first advances in some prosecutions (30 years later) for the State repression and genocide of the past and present, is another step backwards for the people of Guatemala in the struggle to live in a democratic country governed by the rule of law.

The violence and repression of the past and present are directly linked, rooted in the entrenched mechanisms of impunity. The crime networks that terrorize Guatemala today grew out of the State security forces that committed the genocide and atrocities of the 1970s, 80s and early 1990s.

These networks of war criminals (many being former military officers) benefited directly from widespread support from the United States during the “Cold War”. They continued to exercise political and economic control of the nation during the so-called “transition to democracy” in the 1990s. They maintain firm control over many State institutions today.

Unaddressed legacy of Genocide

From the actual genocides of the 1970s and 80s, through the dominance of the FRG political party (headed by former general and dictator Efrain Rios Montt) in the late 1990s and the 2000-2004 presidency, to the ascendancy of Perez Molina, Guatemala continues to grapple with and suffer from the legacy and lack of justice and accountability for genocide.

State Terror in the Ixil Triangle, Nebaj, Quiche

Updated 15 February 2019

Pingback: Desperate For US Aid, The New Guatamalen President Is Denying 36 Years Of War And 200K Dead

Pingback: 36 Years Of War And 200,000 Deaths Ravaged This Country, And Now Its New President Is Denying It All – Finding Out About

As this post states:

“Perez Molina has denied not only participation in war crimes, but has also publicly claimed that genocide did not occur in Guatemala.”

Really? Well, President Clinton disagreed and apologized for the crimes way back in 1999.

(http://www.nytimes.com/1999/03/11/world/clinton-offers-his-apologies-to-guatemala.html)

Pingback: Kill the Messenger: Gary Webb and the Contra-Cocaine Connection | WilderUtopia.com