Surrounded by volcanoes, coffee plantations, and picturesque villages, the once-ruined former colonial capital, Antigua Guatemala, remains the most charming city in the Republic, a vibrant and somewhat overly commodified mix of Ladino-Spanish, Kaqchikel-Maya, and multinational Gringo cultures coming together.

Antigua Guatemala conjures many different attitudes in me. First comes it’s beauty and culture, named by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, the once-ruined third capital of the colonial Kingdom of Guatemala (Captaincy General), founded in 1543. Antigua came about after Kaqchikel-Maya uprisings made the first one untenable, and a lahar or mudflow from nearby Volcan de Agua hit the second, destroying it. On March 10, 1543, the Spanish conquistadors founded present-day Antigua, and named it after its precursor cities, Santiago de los Caballeros (“St. James of the Knights of Guatemala”).

STORY: Maximón: The Underground Great Grandfather of Western Guatemala

My second notion comes from the juxtaposition of hip and trendy Antigua as colonial capital of a country with 23 indigenous language groups. The Kingdom of Guatemala, founded by the cruel and murderous Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado, included most of Central America, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica, as well as the state of Chiapas in Mexico. Spanish chronicler Antonio de Remesal commented that “Alvarado desired more to be feared than loved by his subjects, whether they were Indians or Spaniards,” in his easy recourse to violence.

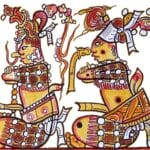

After a brutal campaign to pacify Southern Mexico, Alvarado and his hoard entered the valley of Quetzaltenango (Xelaju), and began dismantling the K’iche’-Maya. Then they moved on to an alliance with the Kaqchickel (or Cakchiquel), whose territory included present day Antigua, and whose glorious Post-Classic historic legends and mythology were recorded in the Annals of the Kaqchikels. The alliance, it seems, came about both because of the fierce K’iche’ defeat, as well as their interest in using the Spaniards to subvert their enemies the Tz’utujil, who reside on the opposite shores of Lake Atitlan.

STORY: Maya Ruins at Tikal: A New Beginning at Winter Solstice

Greedy and most probably insane, Alvarado demanded gold in tribute from the kings of the Kaqchikels, 1,000 gold leaves, which led to the people to desert the then-capital at their historic city of Iximché, fleeing into the forests. The rebellion did not last, as abandoned agriculture and murdered warriors led them to eventually surrender.

So it follows, the foundation where the Spaniards erected those glorious-looking ruins were soaked in greed, blood, and destruction. In this case, Earth’s forces would have the last word. It survived natural disasters of floods, volcanic eruptions and other serious tremors until 1773 when the Santa Marta earthquakes destroyed much of the town.

The preeminent Catholic Church saw these quakes as a sort of divine retribution, and others feared Volcán de Fuego (Volcano of Fire) would cause further disruptions. Thus, authorities relocated the capital to a safer region, which became Guatemala City, the county’s modern capital. Some residents remained in the original town, however, which became referred to as “La Antigua Guatemala.”

STORY: Popol Vuh: The Ancient Maya Dawn of Life and Overcoming the Forces of Awe

For 230 years, Antigua ruled the Central American “kingdom,” with its effective enslavement of the indigenous people, despite Dominican friar Bartolome de las Casas new laws of 1542 which purported to end forced labor. The city, an inspired example of 16th Century Latin American town planning built on an Italian Renaissance-inspired grid pattern with a central park, was known during its prominence as one of the three most beautiful of the Spanish Indies.

Most of the surviving civil, religious, and civic buildings date from the 17th and 18th centuries, with its colonial architecture reflecting a regional stylistic variation known as Barroco antigueño (Antiguan Baroque). Distinctive characteristics of this architectural style include the use of decorative stucco for interior and exterior ornamentation, main facades with a central window niche and often a deeply-carved tympanum, massive buildings, and low bell towers designed to withstand the region’s frequent earthquakes.

STORY: Traditional Healing Among the Highland Maya

Among the many significant historical buildings: the double-arcaded Palace of the Captains General (1549), the Casa de la Moneda, the mostly in ruins Catedral de Santiago (1545), the Universidad de San Carlos, Convent of Las Capuchinas (1736) with its tower of nuns cells built around a circular patio, the yellow La Merced (1749) trimmed in plaster filigree with its massive water-lily-shaped fountain, Santa Clara (1734) with its captivating cloister and gardens, among others, are worth noting.

Don’t miss Antigua Guatemala if you visit the Republic. But make sure you get off track afterwards, hop on what gringos call the “chicken bus” (pejorative and usually baseless term, as chickens are a rare site on buses) and head out into the villages. The novelty of nominally ruined colonial splendor wears off after a few days, but the beauty of the Guatemalan people and their incredible volcanoes must be experienced close-up to be fully-appreciated.

Updated 11 October 2021

Looks and sounds like it was a great trip, Jack. Thanks for sharing Jessica’s beautiful photos and writing the colorful history of the area. Makes me want to visit. 🙂

Pingback: Popol Vuh: The Ancient Maya Dawn of Life and Overcoming the Forces of Awe