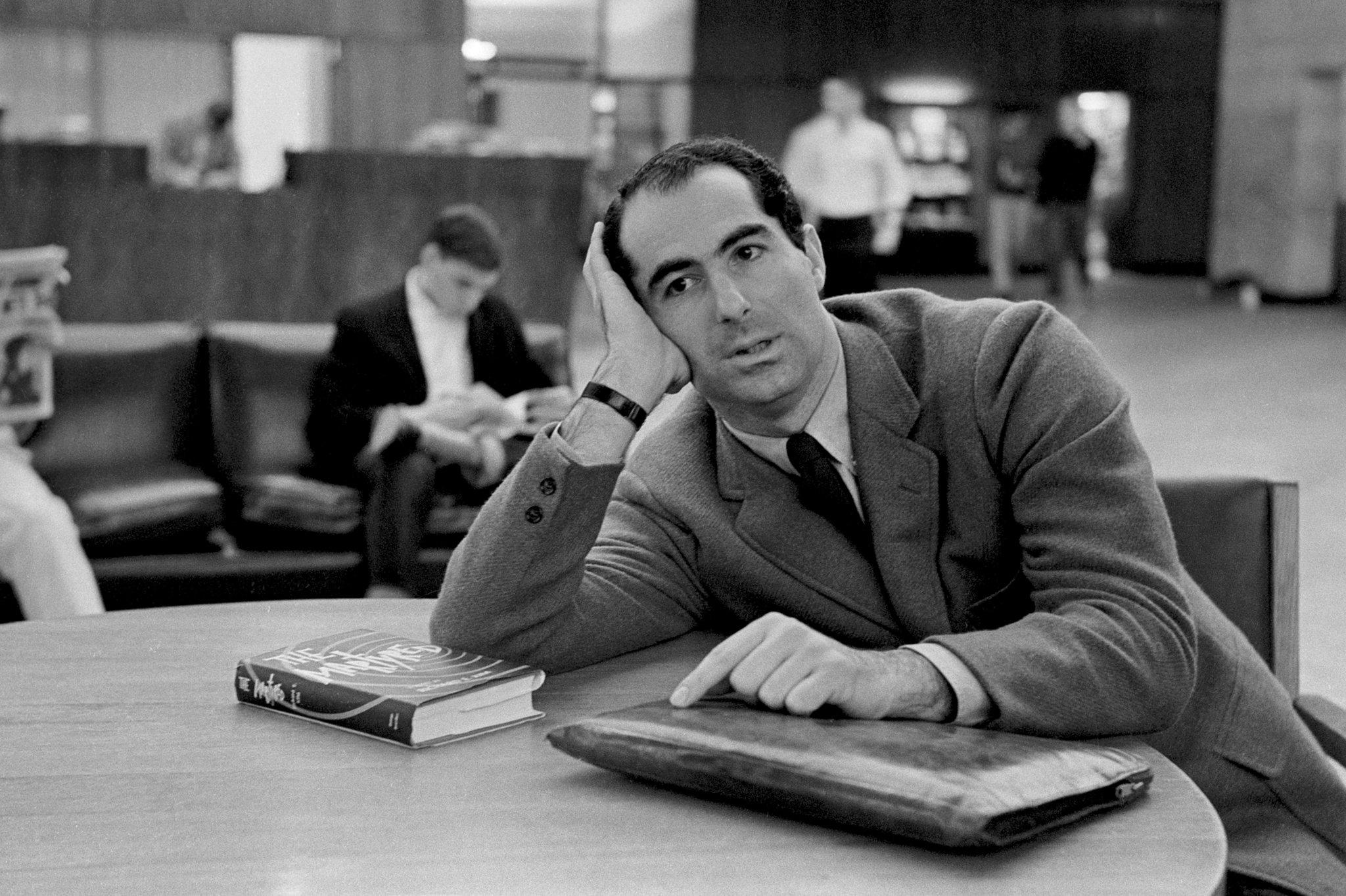

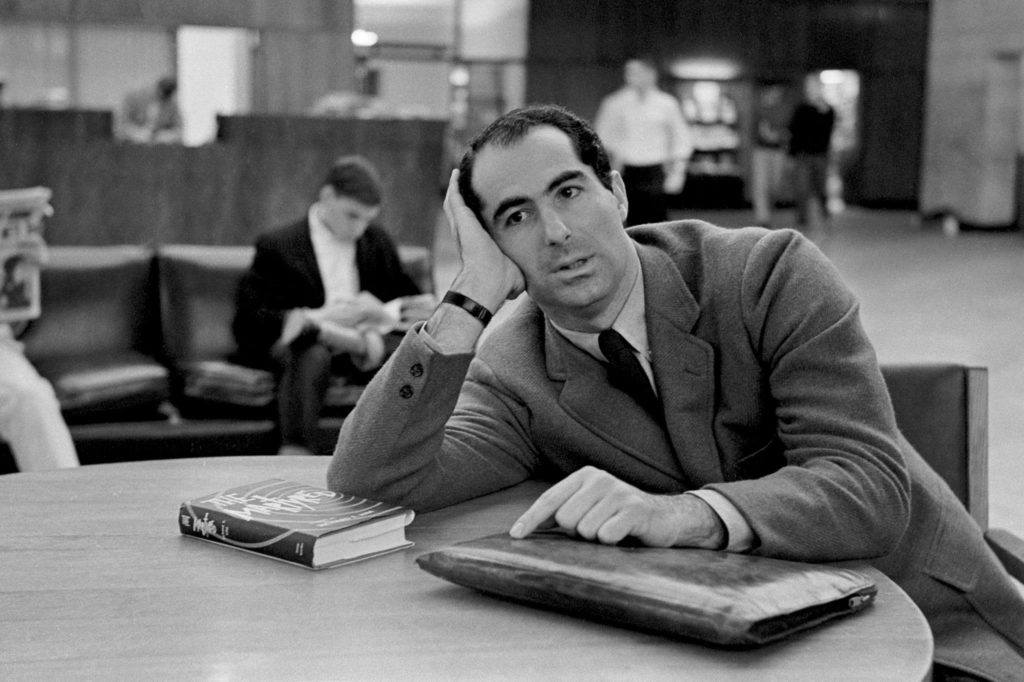

His alter-ego Zuckerman, unconsciously frightened of success and of failure, frightened of being admired and also despised, frightened of being frightened, he unconsciously suppressed his talent, frightened of what it might do next. On the passing of Philip Roth, we look into his often black comic chronicles of an imagined life, his taking down and reshaping the meaning of ‘Jewish American’, and his play at historic re-creating the zeitgeist within the form of the novel.

When He Was Good: Grappling With Philip Roth

By Richard Klin, Published in CounterPunch

One of my bookshelves is entirely filled with the works of Philip Roth (1933-2018). Although an avid reader of his work, there are a host of other writers whose work I love more. My Roth-heavy bookshelf is indicative of many things: a long and prodigious output, for one. His oeuvre was enormous. Much of it was very powerful. Much of it wasn’t. The mountain of work he produced, almost by dint of sheer force, demanded critical attention. It forced its way onto your bookshelf, elbowing its way into a prominent position.

A flood of encomiums and criticism both have followed in the wake of Roth’s passing, which is entirely understandable, given his literary significance and controversy. To me, though, the biggest stumbling block when it comes to doling out the superlatives is its ultimate lack of controversy. There was an underlay of the outdated and out of touch that ran through his work. Being topical is absolutely not synonymous with literary merit, but the fact that Roth no doubt considered his writing an important part of the zeitgeist opens him up to this sort of criticism.

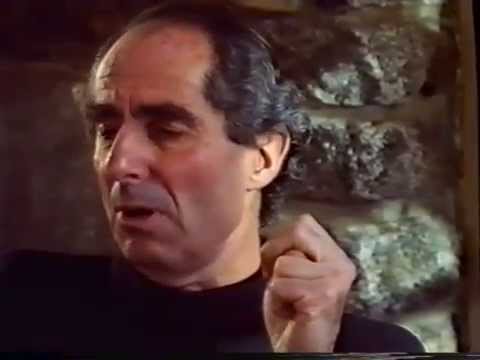

Why write? Philip Roth answered the question in a 1981 interview with Le Nouvel Observateur. He wrote, he said, in order “to be freed from my own suffocatingly boring and narrow perspective on life and to be lured into imaginative sympathy with a fully developed narrative point of view not my own.” — New York Review of Books

Watch this video on YouTube

Arena: Philip Roth, BBC, 1993

I’ve never been able to summon the energy to read Portnoy’s Complaint—not because it’s so incendiary, but because it isn’t. Whether the authorial intent was satiric or not, I could never muster the least bit of interest in tales of horny Jewish boys, domineering Jewish mothers, shicksas, and masturbating into food. (How shocking! How transgressive!) The book, which came out in 1969, was probably ribald for anyone who’d never heard of R. Crumb. Likewise, I’m not sure who would find Roth’s older man–younger woman trope artistically engaging. It feels one step removed from dinner theater. It was as if, in the back of his mind, he was striving to shock Hadassah members or readers in suburbia.

“…we are ambushed…by the unpredictability that is history.” — Philip Roth

Roth’s outdatedness was on display in 2004’s The Plot Against America, his politically prescient rejiggering of history in which Franklin Roosevelt loses the 1940 presidential election to nativist and anti-Semite Charles Lindbergh. Politically prescient, but artistically clunky: “I had no literary models for reimagining the historical past,” Roth observed in an interview—blissfully unencumbered by the knowledge that the recasting of the historical past has a long, entrenched tradition in the science-fiction canon. (Philip K. Dick, anyone?)

But. At full force, his writing was simply extraordinary. The slender Goodbye, Columbus serves as a veritable précis on postwar intra-Jewish class conflict. Neil Klugman, from the less fortunate side of the Jewish street and barely removed from the world of pot roast, boiled potatoes, and “a bottle cream soda,” finds himself amid the wealthy, successful Patimkin family—Jews who have “made it,” but are themselves one step removed from that land of pot roast and boiled potatoes. Neil, wandering through the Patimkin digs, comes across a sturdy old refrigerator—a physical remnant of the Patimkins’ pre-affluent past and now reserved solely for the family’s supply of fresh fruit:

“No longer did it hold butter, eggs, herring in cream sauce, ginger ale, tuna fish salad…rather it was heaped with fruit, shelves swelled with it, every color, every texture…. There were greengage plums, black plums, red plums, apricots, nectarines, peaches, long horns of grapes, black, yellow, red, and cherries, cherries flowing out of boxes and staining everything scarlet.” That is astonishing writing: a familial and historical metamorphosis in one paragraph—all conveyed via the opening of a refrigerator door.

Then there is the sprawling American Pastoral, the fictional chronicle of Swede Levov’s odyssey through postwar and 1960s America. Roth employs a literary sleight-of-hand so adroit it can almost be overlooked. American Pastoral is Nathan Zuckerman’s—Roth’s fictional alter ego—imagining the details of Swede Levov’s life. It is a monumental, yet masterfully subtle device, which adds a patina of slight unreality to the novel.

“Where the mass media inundate us with inane falsifications of human affairs,” Roth wrote in 1990, “serious literature is no less of a life preserver, even if the society is all but oblivious of it.”

The Counterlife ranks as my favorite Roth, which again employs Nathan Zuckerman as its protagonist and sometimes narrator, utilizing contrasting narratives that in lesser authorial hands would be hackneyed. Philip Roth was always fearless in letting his fictional stand-ins come across as cretins (or it may be he had no choice in the matter), but The Counterlife displays an advanced psychological subtlety. Like Roth himself, Nathan Zuckerman–“The Jersey boy with the dirty mouth who writes the books Jews love to hate” as another Counterlife character describes him—is a writer whose scabrous books have rendered him a smutty apostate to much of the American Jewish world. To the wider gentile world, Zuckerman’s a chronicler of the Jewish grotesque. A large chunk of The Counterlife places Zuckerman in Israel, where one would imagine—politics aside—that a writer so unceasingly consumed with Jewishness would find some bare-bones affinity to what is, after all, a Jewish country. But Zuckerman exhibits a core indifference to Israel, to the point of not even being able to distinguish between Hebrew and Arabic. And almost as a finale, Zuckerman marries an English gentile and comes up against his own spouse’s unfamiliarity with Jews, as well as a bracing dose of British anti-Semitism. And so Nathan Zuckerman is always out of place, always in contrasting opposition. And always, hence, the perpetual center of attention.

“The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong.” — Philip Roth, American Pastoral

“Unless one is inordinately fond of subordination, one is always at war.” — Philip Roth

What Philip Roth didn’t know filled volumes. What he did know filled fewer volumes, but those volumes were crucial. (One of the most intriguing things about Roth was his seemingly anomalous friendship with the late Israeli writer and Holocaust survivor Aharon Appelfeld, something that deserves a book of its own.) There was a lot of dross in Roth’s outsized canon. But amid the dross was also pure gold.

Updated 27 July 2021