Among the Caddo People of Oklahoma, the Coninisi or those who know the spirit medicine through the Ghost Dance religion and the Native American Church, took on the role of mediating relationships between the visible and invisible realms of the world, and between the living community and the souls of deceased ancestors. Thus, despite a tragic history, a people survives today.

History of the Caddo Nation

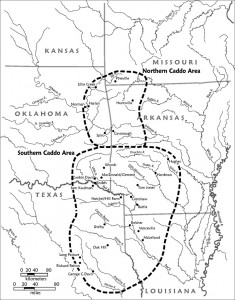

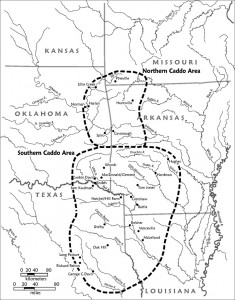

The ancestors of the Caddo Indians were agriculturalists whose distinctive way of life and material culture emerged by A.D. 900, as revealed in archaeological sites in Southern Arkansas, Northern Louisiana, East Texas, and Southern Oklahoma. The Caddo first encountered Europeans in 1541 when the Hernando de Soto Expedition came into the Mississippi Valley. With later arrival of missionaries from Spain and France, a smallpox epidemic broke out that decimated the population. Measles, influenza, and malaria also devastated the Caddo, as these were Eurasian diseases to which they had no immunity. “Texas” comes from the Hasinai Caddo word táysha, meaning “friend.” The Caddo people further suffered hardships when the United States government removed them from their ancestral rivers and streams to reservations in Texas and later Western Oklahoma during the nineteenth century.

The Ghost Dance Religion

When the Ghost Dance [Nanissáanah] was introduced to the Caddos in 1890, they adapted it to long held religious beliefs. A Nevada Paiute named Wovoka (also known as Jack Wilson) prophesied dancing would reunite the living with the spirits of the dead and bring peace, prosperity, and unity to native peoples throughout the region, and the Ghost Dance spread as a two- four- or five-day round dance. From the time of the oldest ancestors, Caddos believed: Ah-ah-ha’-yo, father above, hears our daily prayers; he provides and protects us; there is a world beyond this one where our people gather after leaving Mother Earth.

The Ghost Dance took place in a circle around a pole carved from the heart of a tall cedar tree. Painted black on one side, green on the other, it was erected with the black side facing north, the green side south. The leader stood on the dividing line or “road” at the west side of the pole. Facing east, he began the first song telling that the feather signifying the right to lead the Ghost Dance was given to seven men. Sometimes a person in the dance-in-a-circle would fall in a trance. On waking, the person would tell of a vision and a new song would be made. Sometimes healing miracles occurred.

In the old stories from Mexico, peyote is originally a women’s medicine associated with water, and is called the Grandmother. The story goes as follows: A woman walked through the desert, out of water and getting thirsty. She heard singing, looked around and saw no one but the song continued. She searched the ground without finding anything but then the voice said, “I am here. I am on the ground.” She parted the brush and saw a Peyote button. The Peyote said to the woman “Eat me I am full of water.”

Wavoka’s Ghost Dance vision came during a total eclipse of the sun. He foretold of a coming natural disaster that would devastate the White world and allow the native people to return to their lands and way of life. The speed and fervor with which the movement spread sparked panic among white settlers and authorities and figured prominently in the events that led to the massacre at Wounded Knee.

STORY: Lakota Vision: White Buffalo Calf Woman and World Harmony

Ghost dancing relieved uncertainty that clouded the hopes of Caddo people. John Moon-head Wilson, a Delaware-Caddo, was one of the charismatic leaders who helped spread the Ghost Dance. In 1880, Wilson had become a peyote roadman. The tribe had known the Half Moon peyote ceremony, but Wilson introduced the Big Moon ceremony to them. Other religious dances and ceremonies were only initiated by women, and women today play an important role in the furthering of traditions to the next generations. The Caddo tribe continues to practice the Ghost Dance and remains active in the Native American Church today.

STORY: Plant Medicine: Indigenous Wisdom for a Troubled World

Origin of the Medicine Men and Women

In days of old people knew the animals and were on friendly terms with them. All animals possessed significant powers and they sometimes appeared to people in dreams or visions and gave them their power. Often when men were out hunting, left alone in the forest or on the plains at night, the animals came and spoke to them in dreams and revealed their secrets.

One man who had had a dream of this kind woke up and went home. There he remained several days in silence, refusing to talk to any one, thinking only of the things that had been revealed. After a time he called some of his friends and the old men of the tribe to his lodge and told them of his powers. He asked if they wanted to learn his secrets. If they agreed the man would teach them his songs and dances. They agreed, so he taught them all the necessary things. Then they held a medicine men’s dance and gave themselves the title of medicine men and women. Then if any one was sick in the village and sought their aid, they prepared to hold the dance on behalf of that person and built a large grass lodge where the dance was held for six days and nights.

There are two kinds of medicine men and women. One kind has power to doctor and heal the sick; another has the power to prevent any one from being hurt or harmed, and can charm away all danger. The latter, called xinesí or priest-chiefs, are supposed to be more powerful than the first kind of medicine healers, for they can perform their magic without medicine and have power to bewitch people who are afar off, and thus make them lose their minds and not know what they are doing. They have a song of death that can scare death away from a dying person. There are few people who ever receive this power, which is generally given by the sun, moon, stars, earth, or storm, but some very wild and ferocious animals can also give the power to people. It is documented that women held this religious and political authority as far back as 600 AD.

STORY: David Swallow Jr: People Connected Through Spirit and Sacred Places

Connas or coninisi, the first kind of Caddo medicine healers, were said to use herbs and various ritual practices such as smoking, sweating, incantations, and divination to cure sickness and heal the wounded. While the Spanish were distrustful of the medicine men, they also observed successful healing and realized that some of the herbal remedies were potent. Many of the curing ceremonies involved practices the Spanish associated with the devil. The Spanish priest Espinosa as translated by Bolton describes one such event.

To cure a patient they make a large fire [under the bed] and “provide flutes and a feather fan. The instruments [palillos] are manufactured [sticks] with notches resembling a snake’s rattle. This palillo [rasp] placed in a hollow bone upon a skin makes a noise nothing less than devilish. Before touching it they drink their herbs boiled and covered with much foam and begin to perform their dance without moving from one spot, accompanied by the music of Infierno, or song of the damned, for only in Inferno will the discordant gibberish which the quack sets up find its like. This ceremony lasts from mid-afternoon to nearly sunrise. The quack interpolates his song by applying his cruel medicaments.

It is unlikely that the medical practices of 17th century Europe would be viewed by us today as any more sound or less superstitious than that of the 17th century Caddo. The Spanish and French witnessed and sometimes harshly described a Caddo society that had a complex and quite sophisticated set of beliefs and practices about the natural and supernatural world. It is only to be expected that the two worlds were foreign to one another and that neither side really understood the other.

Through the different practices of spiritual traditions, carrying the medicine to the people and educating generations inside and outside of native communities, the vibrant culture of the Caddo persists today.

Sources

First Encounters, By the Arkansas Archaeological Survey and the University of Arkansas

Parsons, Elsie Clews. Notes on the Caddo, Memories of the American Anthropological Association. Supplement to American Anthropologist, Volume 43, No. 3, Part 2. 1921. AccessGenealogy.com. Web. 31 March 2014. http://www.accessgenealogy.com/native/caddo-ghost-dance-nanisana.htm – Last updated on May 7th, 2013.

Texas Beyond History, University of Texas at Austin.

Updated 3 May 2021

Pingback: Caddo Indian Research

Pingback: Plant Medicine: Indigenous Wisdom for a Troubled World - WilderUtopia