Ecuadorian state capitalism has sacrificed significant tracts of one of the planet’s most important biosphere reserves, Yasuni National Park in the Amazonian region, to a massive new oil drilling project. It threatens multiple indigenous territories and the area’s biodiversity and ecosystem integrity.

Yasuni Oil Exploration Programme – A Major Threat to Important Biosphere Reserve

By Huw Hennessey

What is the drilling project and how much oil might be found here?

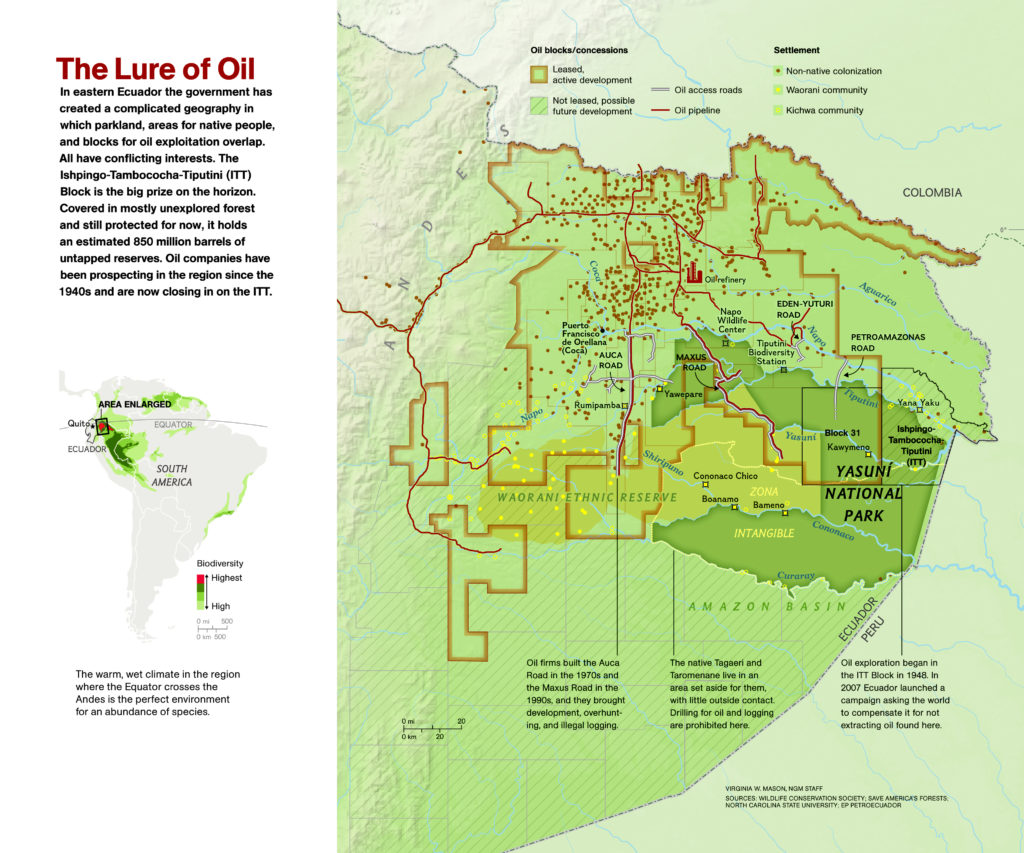

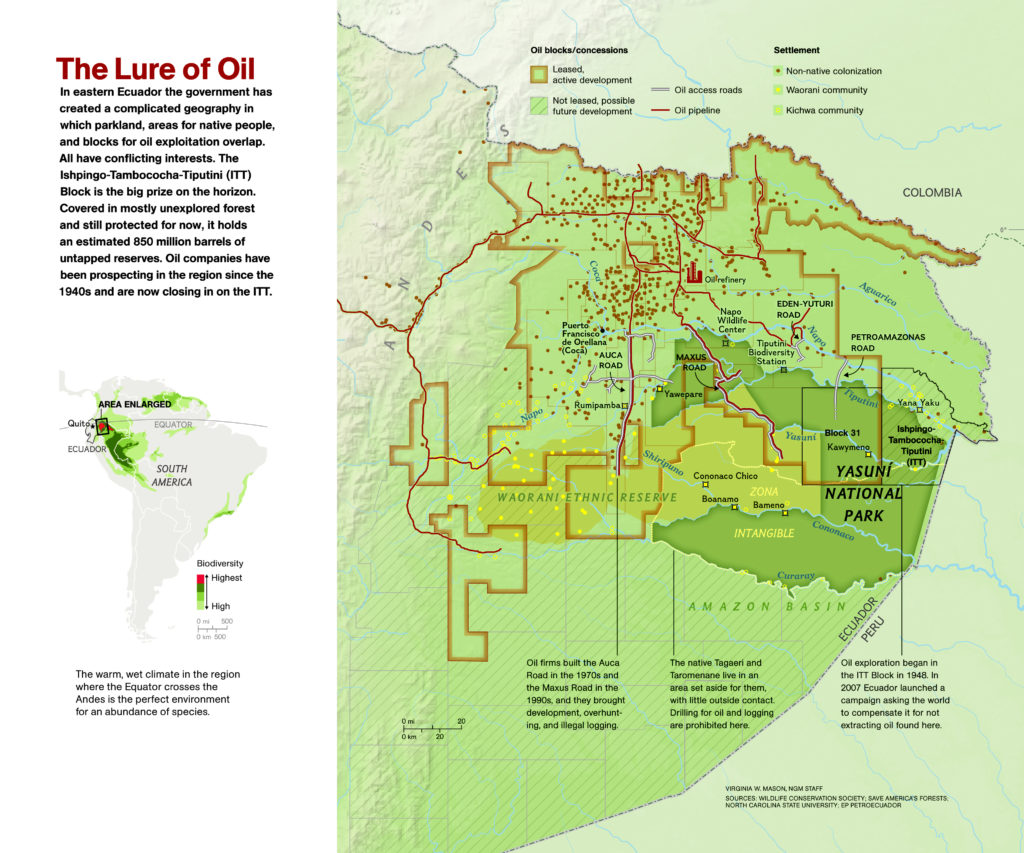

The government has launched a massive oil exploration project in the eastern Ecuadorian Amazon, covering some 6,500 square miles. Estimated reserves of some 920 million barrels make this the largest deposit in the country. Preparatory exploration began in 2014, with the first drilling operations in March 2016.

Two fields have been explored to date: Tiputini and Tambococha, which comprise the so-called Block 43 or ITT (Ishpingo-Tamboccocha-Tiputini). In total, the ITT is aiming to produce up to 200,000 barrels a day by 2019. The work would comprise 360 oil wells, including 300 inside the Yasuní National Park.

The current drilling work is being carried out by Petroamazonas, the upstream arm of state oil company Petroecuador, with prior (and possibly ongoing) involvement by SINOPEC, the Chinese state oil company.

“Where the environment is destroyed, our identity is destroyed as this interrupts the relationship between nature and our people,” said Romulo Akachu, vice president of Ecuador’s national indigenous federation (CONAIE) and representative of the Shuar Nation, where oil drilling has not commenced.

STORY: Ecuador: Battle Between Living Systems and Oil at Yasuní National Park

Did the government and Petroamazonas announce the proposed project openly and transparently to the public?

The government is required to secure Congressional approval for any oil exploration license, taking into account its environmental impact.

Block 43 was given an environmental licence by the Department of the Environment in May 2014; the government also requested permission from Congress to extract oil from Block 31, which lies within the Yasuní National Park. Nevertheless, Petroamazonas began to develop that block’s Apaika-Nenke field in early 2012, without congressional approval. Opponents to the project have also protested that no licence should have been given in the first place, for potentially harmful activity within a protected area, and that work had already taken place before the application was submitted.

According to the director of the Huaorani Eco-Lodge (see below), proposals were not discussed in advance with everyone in the local community. Some 850,000 opponents to the project signed a petition, but the government rejected it, saying 300,000 signatures were duplicated or falsified, but disregarding the remaining half a million genuine petitioners.

In a 2012 interview in New Left Review, Correa dismissed his left critics as romantic reactionaries who see the poverty of rainforest people as “something folkloric.” He has even less patience these days for those who want to keep the oil in the Amazonian soil. Invoking “the classic socialist tradition” of “Marx, Engels, Lenin, Mao, Ho Chi Minh and Castro,” none of whom “said no to mining or natural resources” Correa insists that, without extraction, what he has called the “twentieth-century socialism” of the Andean countries “will not be able to offer any viable political projects.” — The Nation

STORY: Correa’s Ecuador: Police Insurrection Fails as Coup But Challenges Remain

How much does it cost and who is paying?

SINOPEC (PetroChina) loaned US$1 billion to Ecuador, to be repaid over two years, at an interest rate of 7.25 percent. Further loans totaling US$5 billion have also been offered to covering the running costs of the ITT field, with a proposed 50-50 split of profits to be shared by SINOPEC and the Ecuadorian government.

The credit flow from Beijing has only widened and deepened ever since—in return for an ever-larger percentage of the country’s oil production. [In 2013], Chinese funds were estimated to cover 61 percent of the government’s $6.2 billion in financing needs and, in return, China claimed the lion’s share of Ecuador’s oil. — The Nation

What is so special about the Yasuní National Park?

UNESCO has declared this park a Biosphere Reserve, as “one of the most biologically diverse” regions on earth, with some 4,000-plant species, 173 species of mammals and 610 bird species living here. It contains more documented insect species than any other forest in the world, and is among the most diverse forests in the world for different species of birds, bats, amphibians, epiphytes, and lianas. Yasuní is critical habitat to 23 globally threatened mammal species, including the Giant otter, the Amazonian manatee, Pink river dolphin, Giant anteater, and Amazonian tapir. Ten primate species live in the Yasuní, including the threatened White-bellied spider monkey.

A second issue has to do with whether it would be right to simply stop extracting oil before we have completed or even engineered the transition to a non-primary economy. Aside from the collapse of the Ecuadorian state, it would mean a sharp return to the plantation economy (and owner!), a dramatic reduction of resources to tackle poverty (one of the principal causes of environmental degradation in the first place), and no capital to invest in the diversification of our economy. – Guillaume Long, Ecuador’s Minister of Culture

What environmental restrictions have been imposed on the ITT project? Are they being adhered to and monitored?

Although Petroamazonas was committed to adhere to certain conditions, it has already broken several of these commitments, including the building of much bigger and wider access roads in the park. Also, the Ecuadorian army has set up guard posts around the fields, prohibiting public access, as a further sign of their covert strategy. Few outside observers have managed to enter the area, but NGO Amazon Watch did get in and produced a film in 2015, showing illegal access roads of nearly 30 meters wide, more than twice the permitted width.

Manari Ushigua, President of the Sápara federation, whose territory is almost totally engulfed by Blocks 79 and 83, also addressed the government’s intentions. “The goal of the Ecuadorian government is to divide us and open our land to oil extraction. We live in peace, with the natural world, with our spirits. But our elders are few. We are on the verge of extinction.” — Amazon Watch

httpvh://youtu.be/enyAg0jsS9w

In an exclusive investigation for reported.ly, journalist Nina Bigalke traveled to an oil concession deep in the Amazon rainforest to film an illegal access road, the existence of which Ecuador’s government has denied. As indigenous peoples seek to secure the safe future of their ancestral home, President Rafael Correa faces fierce political opposition ahead of a huge expansion of oil production into Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park.

What impact has the project already had on the region?

It has already caused significant harm to the area’s important tourism industry, causing the closure of the award-winning, community-run Huaorani Eco Lodge, on the fringes of Yasuní National Park.

Plus, excessive access roads are causing deforestation and fragmenting the wildlife’s contiguous territory. There is also widespread concern about the risk of oil leaks and pollution, prompted at least partly because of Petro-Amazonas’ appalling record in the region; with massive oil spills from Chevron-Texaco pipelines in the same area, dating back to the 1970s and the subject of unsettled multi-billion $$ lawsuits.

What happened to the Yasuní-ITT Initiative?

President Rafael Correa launched this environmental programme – to keep the huge oil reserves underground in the Amazon in return for ‘carbon credits’ to be paid for by the international community – in 2007. It was scrapped in August 2013, as only some 10% of the required sum was raised (Correa claimed that of the US$3.6 billion in contributions sought, the trust fund only reached $13 million in actual donations and $116 million in pledges).

With the failure of the initiative, Correa then announced that oil exploration would have to begin, to help pay off Ecuador’s sizeable foreign debt.

[vimeo clip_id="11013770" width=600 height=338 ]WAORANI Last Of the Rain Forest People, a film by J. Michael Seyfert