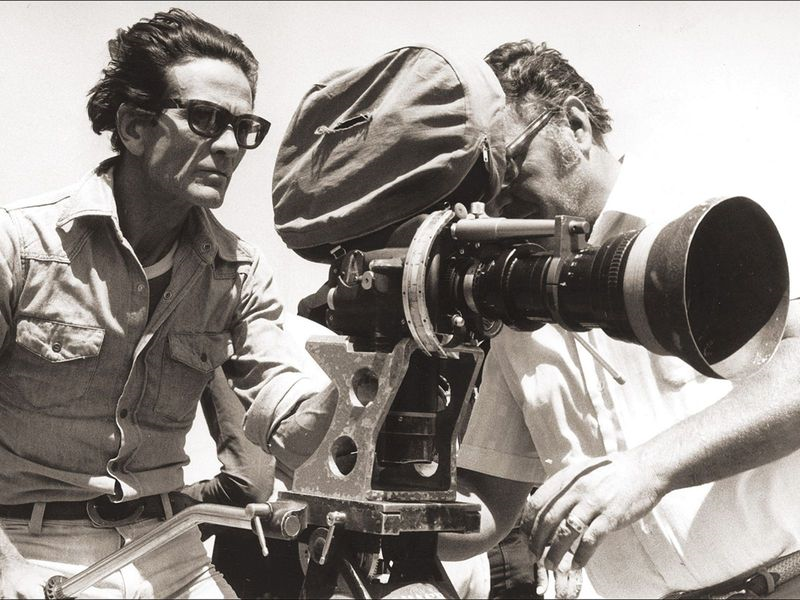

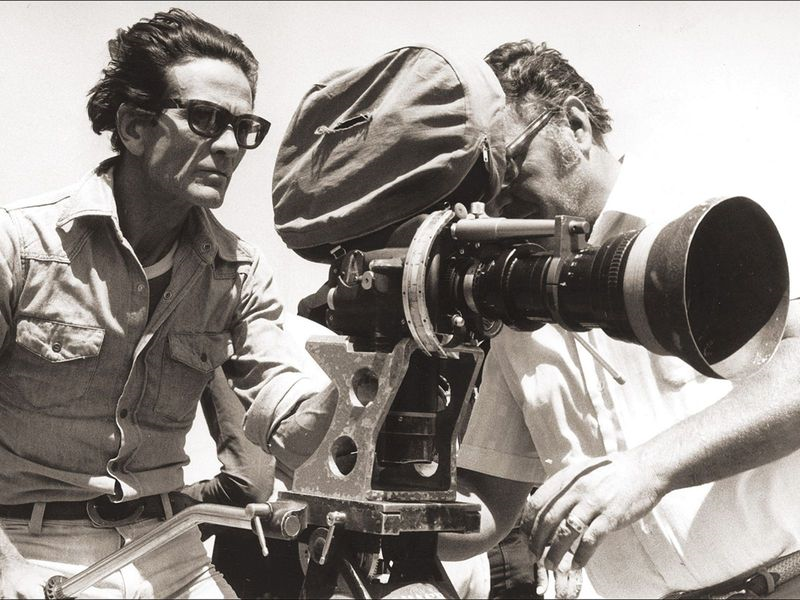

Champion of the disinherited of postwar Italy, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s masterworks prefigured his country’s fall to a consumerist Heart of Darkness, an uncompromising vision that may have led to his own wretched death. A biopic by Abel Ferrara that premiered at the 2014 Venice biennale reconstructed the last hours of the Italian film director, who was murdered in 1975.

Who really killed Pier Paolo Pasolini?

By Ed Vulliamy, An Excerpt from the Guardian UK

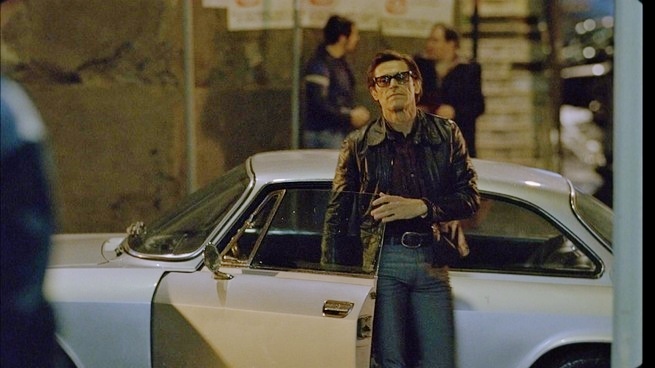

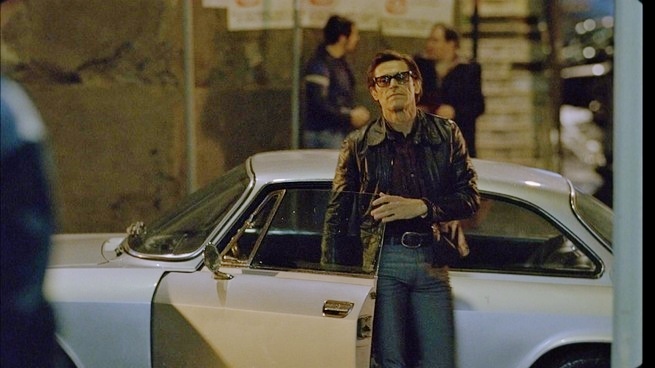

In the early morning of November 2, 1975, in Idroscalo, a terminally dreadful shanty town in Ostia, outside Rome, the body of Pier Paolo Pasolini, then 53, an intellectual powerhouse and one of the greatest filmmakers of the 1960s and 1970s, was found badly beaten and run over by his own Alfa Romeo.

“Want to go for a spin?” the poet and maestro of Italian cinema asked the rent boy, according to the latter’s confession to the police. “Come ride with me, and I’ll give you a present.”

So began the events leading to the murder of Pier Paolo Pasolini, brilliant intellectual, director and homosexual whose political vision – based on a singular entwinement of Eros, Catholicism and Marxism – foresaw Italian history after his death, and the burgeoning of global consumerism. It was a murder that, four decades later, remains shrouded in the kind of mystery and opacity Italy specializes in – un giallo, a black thriller.

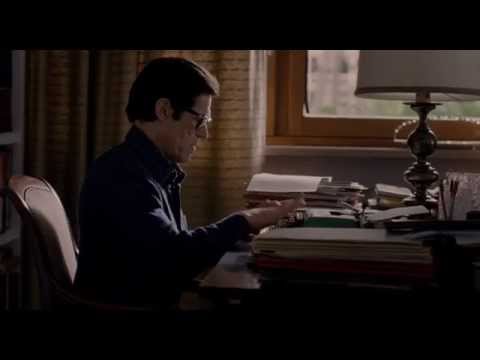

Watch this video on YouTube

Trailer for Pasolini, By Abel Ferrara, Starring Willem Dafoe

“Members of the establishment may use a board of directors or a stock exchange manoeuvre; people from more disadvantaged classes may use a metal bar. You essentially use a metal bar to violently obtain what you want. But why do you want it? Because they told you that wanting something is a virtue and you are therefore exercising your right-virtue. So you’re a murderer, but you’re essentially good.” — Pier Paolo Pasolini, interviewed on the day of his death by Furio Colombo

The encounter occurred in the miasma of hustling around Roma Termini railway station at 10.30pm on 1 November 1975. And it marks the point of departure for a film tipped to win the Golden Lion at the Venice biennale festival this August – Pasolini, starring Willem Dafoe and directed by Abel Ferrara, Bronx-born of Italian descent. The film deals with the last day of an extraordinary life. Ferrara says: “I know who killed Pasolini,” but will not give a name. But in an interview with Il Fatto Quotidiano, he adds: “Pasolini is my font of inspiration.”

STORY: Pier Paolo Pasolini: A Subversive Champion of the Disinherited

https://youtu.be/fBh-uemW7mA

A Film Maker’s Life by Carlo Hayman-Chaffey, a short documentary made in 1971 about Pasolini

A Political Murder Like a Greek Tragedy

At 1.30am, three hours after the station rendezvous, a Carabinieri squad car stopped a speeding Alfa Romeo near the scrappy coastal promenade of Idroscalo at Ostia, near Rome. The driver, Giuseppe (Pino) Pelosi, 17, sought to run, and was arrested for theft of the car, identified as belonging to Pasolini. Two hours later, the director’s body was discovered – beaten, bloodied and run over by the car, beside a football pitch. Splinters of bloodied wood lay around.

Pelosi confessed: he and Pasolini had set off, and he had eaten a meal at a restaurant the director knew, the Biondo Tevere near St Paul’s basilica, where he was known. Pino ate spaghetti with oil and garlic, Pasolini drank a beer. At 11.30pm they drove towards Ostia, where Pasolini “asked something I did not want” – to sodomise the boy with a wooden stick. Pelosi refused, Pasolini struck; Pelosi ran, picked up two pieces of a table, seized the stick and battered Pasolini to death. As he escaped in the car, he ran over what he thought was a bump in the road. “I killed Pasolini,” he told his cellmate, and the police.

For Pasolini, the new generation [who survived infant mortaility with the help of 1950s science] was “infinitely more fragile, brutish, sad, pallid, and ill than all preceding generations.” They are depressed or aggressive. And “nothing may cancel the shadow that an unknown abnormality projects over their life.” Nowadays, this interpretation can easily explain the alienated, cross-border Islamic youth who joins a jihad in desperation. — Pepe Escobar, CounterPunch

Pelosi was convicted in 1976, with “unknown others.” Forensic examination by Dr. Faustino Durante concluded that “Pasolini was the victim of an attack carried out by more than one person.”

On appeal, however, the “others” were written out of the verdict. Pelosi had acted alone and the master was dead in a squalid tryst gone wrong and best forgotten, perhaps even deserved. But fascination with Pasolini and his films (in Italy, his writing too) increased – as did that with mysteries that still hang over his last hours.

The Perennial Reconsideration of Pasolini

The renown of his work is manifestly on merit: New York’s MOMA mounted a retrospective in 2012, the BFI in 2013. In April this year the Vatican, which had once pursued Pasolini and helped secure a criminal conviction for blasphemy, declared his masterpiece, The Gospel According to St Matthew, “the best film ever made about Jesus Christ.” This expression of Pasolini’s radical faith portrays Jesus as a revolutionary “red Messiah,” according to the Franciscan doctrine of holy poverty, which in part influences the current pontiff, Francis.

But the compulsion of his death is less explicable: in 2010 the former mayor of Rome and leader of the center-left Democratic party, Walter Veltroni, demanded that the case be reopened on the basis of a convergence of strange, and politically charged, circumstances.

The accused came from a housing estate outside Rome called Tiburtino III. Built in 1935 on marshland, the fascist-era tenements never amounted to the utopian project promised by Mussolini. Yet the outskirts, strewn with broken washbasins and old tyres sprouting poppies, present a Pasolinian pasticcio of the poetic and the squalid. In Pasolini’s day Tiburtino III retained something of the semi-rural atmosphere of l’Italietta (Italy’s little homelands) peculiar to his Roman cinema. — Ian Thomson in the Guardian

Pasolini was killed the day after his return from Stockholm, where he had met Ingmar Bergman and others in the Swedish cinematic avant-garde, and given an explosive interview to L’Espresso magazine. In it, he addressed his favorite theme: “I consider consumerism to be a worse form of fascism than the classic variety.”

[Pasolini] deftly configured the “cynicism of the new capitalist revolution – the first real rightist revolution.” Such a revolution, he argued, “from an anthropological point of view – in terms of the foundation of a new ‘culture’ – implies men with no link to the past, living in ‘imponderability.’ So the only existential expectation possible is consumerism and satisfying his hedonistic impulses.” — Pablo Escobar

Pasolini’s view of a new totalitarianism whereby hyper-materialism was destroying the culture of Italy can be seen now as brilliant foresight into what has happened to the world generally in an internet age. But his critique had been, for months before the murder, more specific. He had singled out television as an especially pernicious influence, predicting the rise and power of a type such as media-mogul-turned-prime minister Silvio Berlusconi long before time. More specific still, he had written a series of columns for Corriere della Sera denouncing the leadership of the ruling Christian Democratic party as riddled with Mafia influence, predicting the so-called Tangentopoli – “kickback city” – scandals 15 years later, whereby an entire political class was put under arrest during the early 1990s. In his columns, Pasolini declared that the Christian Democratic leadership should stand trial, not only for corruption but association with neo-fascist terrorism, such as the bombing of trains and a demonstration in Milan.

Again, a spine-chilling vindication: these were the so-called “years of lead” in Italy, culminating in the bombing of Bologna station five years after Pasolini’s death by neo-fascists working with the secret services, killing 82 people.

For the entire article, read it at the Guardian.

Also read: “We Are all Living Pasolini’s ‘Theorem,'” By Pepe Escobar, in CounterPunch.

Pingback: Pier Paolo Pasolini: A Subversive Champion of the Disinherited | WilderUtopia