The shamans of the nomadic peoples of Siberia and Mongolia guard a sacred alliance between migrating reindeer and the ancestor spirits of the taiga forest.

Reindeer Dance of the Evens of Siberia

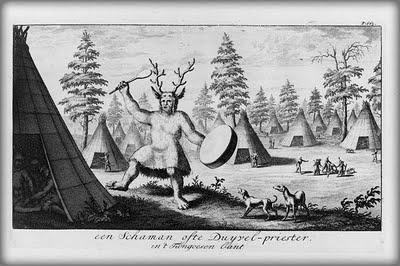

In Siberia, shamans have an expressed connection with reindeer imagery combined with bird-flight. They often dressed in imitation reindeer antlers, tipped with wings or feathers, placed on their headdress. On mummies found in the Pazyryk Valley, tattoos and drawings on tombs include stylized reindeer with wings attached at the shoulders. Like the participants in the Eveny (Evenki) midsummer ritual, shamans may ride to the sky on a bird or a reindeer.

The association between reindeer and flying is very ancient — much, much older than European or American ideas about Santa Claus. Scattered across the deserts and steppes of western Mongolia and stretching into the Altai Mountains in the west and up to the border of Manchuria in the east, stand ancient ‘reindeer stones [depicting flying]’ dating from the Bronze Age some 3,000 years ago. — Piers Vitebsky, ‘The Reindeer People’

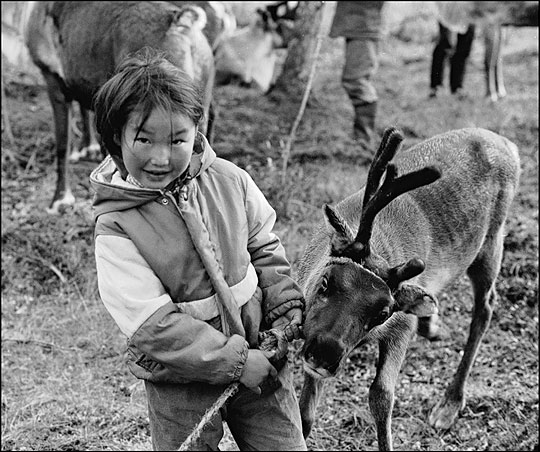

Piers Vitebsky is an anthropologist who studies the Eveny or Reindeer People of Siberia. They depend upon them for survival, keeping herds for meat, but also possess a deeper connection. Vitebsky says they also have a personal, consecrated reindeer animal doubles, which they believe will die for them.

Piers Vitebsky – “The Reindeer People” – Like the participants in the Eveny (and the related Evenki) midsummer ritual, shamans may ride to the sky on a bird or a reindeer. But their relationship with these animals goes far beyond mere riding. One shaman is suckled by a white reindeer during his initiatory vision as he incubates in a bird’s nest on a branch high in the tree that links earth and sky.

Another becomes a reindeer himself by wearing its hide, while hunters with miniature bows and arrows surround him and mime the act of killing. The hide is then stretched across the broad, flat drum that the shaman will beat as accompaniment to his trance. Another shaman, seeking to consecrate his reindeer-skin drum, is guided by spirits as he combs through the forest to find the location where the reindeer was born and traces every place it has ever visited over the course of its life, right up to the point where it was killed.

As he picks his way through bogs and over fallen branches, he picks up the scattered material traces of its existence — snapped twigs, dried dung — to gather together every possible part of its being, and then molds them into a small effigy of the reindeer. When he sprinkles the effigy with a magical ‘water of life’, the drum comes to life. Like a reindeer itself but with enhanced power, it is now capable of bearing the shaman aloft with its throbbing beat to nine, twelve, or more levels of the heavens.

The reindeer-herding peoples who make up the South Siberian and Mongolian Reindeer-Herding Complex include the Dukha of northwestern Mongolia, the Tozhu of the Republic of Tyva, the Tofa of Irkutsk Province, the Soyot of the Buryat Republic, and the Evenki, who range throughout south Siberia and into the northern tip of China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Inhabiting a fragile transition belt of taiga and alpine tundra between the Siberian boreal forest and the Inner Asian steppes, these peoples represent the southernmost extreme of reindeer pastoralism in the world.

The Reindeer People of Mongolia

Watch this video on YouTube

In Northwestern Mongolia, there exists a sacred alliance between people, ancestor spirits and reindeer. This collection of films portrays the Tsataan and Dukha reindeer nomads following their migration through the forests of Mongolia’s Hovsgol province.

I still do not understand how the old Eveny acted out the experience of flying through the air, but they would mime their return to earth by sitting on their own reindeer as if they were arriving from a long journey, expressing tiredness, unsaddling their mount, pitching a tent and lighting a fire. This rite was followed by a hedje, a circle dance in the direction of the sun, and a feast of plenty. — Piers Vitebsky

They move with a herd of about a hundred reindeer through a sacred taiga or boreal forest inhabited by the spirits of their ancestors, who communicate to the living through songs. In a film by Hamid Sardar, the oldest Dukha, is a divine seer, a 96-year old shaman, called Tsuyan. She is the link between the healing songs of the forest ancestors, her people and their reindeer. She is the centerpiece of an extraordinary coexistence in one of the wildest regions of Mongolia – where people still live and hunt in a forest dominated by supernatural beings. To live in harmony with them, people had to learn to respect nature and animals and to pass down their beliefs, from generation to generation, by invoking the song-lines of their deceased ancestors.

The Troubled Taiga: Threats to the Reindeer Husbandry Way of Life

From Cultural Survival: The peoples who make up the South Siberian and Mongolian Reindeer-Herding Complex all are confronting, to varying degrees, similar threats to their cultural survival, including transitions to market-based economies, land privatization, mineral extraction, tourism, global warming, language endangerment and loss, and assimilation into the dominant Russian, Mongolian, and Chinese cultures.

These peoples have a combined population of approximately 10,000, which represents only a small fraction of the total in the regions they inhabit. Of these 10,000, however, fewer than 1,000 are still actively involved in reindeer husbandry. This disparity is due in large part to the drastic decline in the numbers of domesticated reindeer. About 3,500 domesticated reindeer remain in the region, down from 15,000 just a decade ago.

Updated December 26, 2015

Hi there,

very interesting article. I remember reading somewhere that they accomplished the trip to the sun through the hallucinogenic action of some flowers being burned in a fire and human inhalation of this hallucinogenic smoke. That or I surmised it after reading the account of their trip to the sun.

Pingback: A MIKULÁS TÉNYLEG LAPPFÖLDR?L JÖN, CSAK ÉPP EGY BEGOMBÁZOTT SÁMÁNRÓL MINTÁZTÁK - Északhírnök