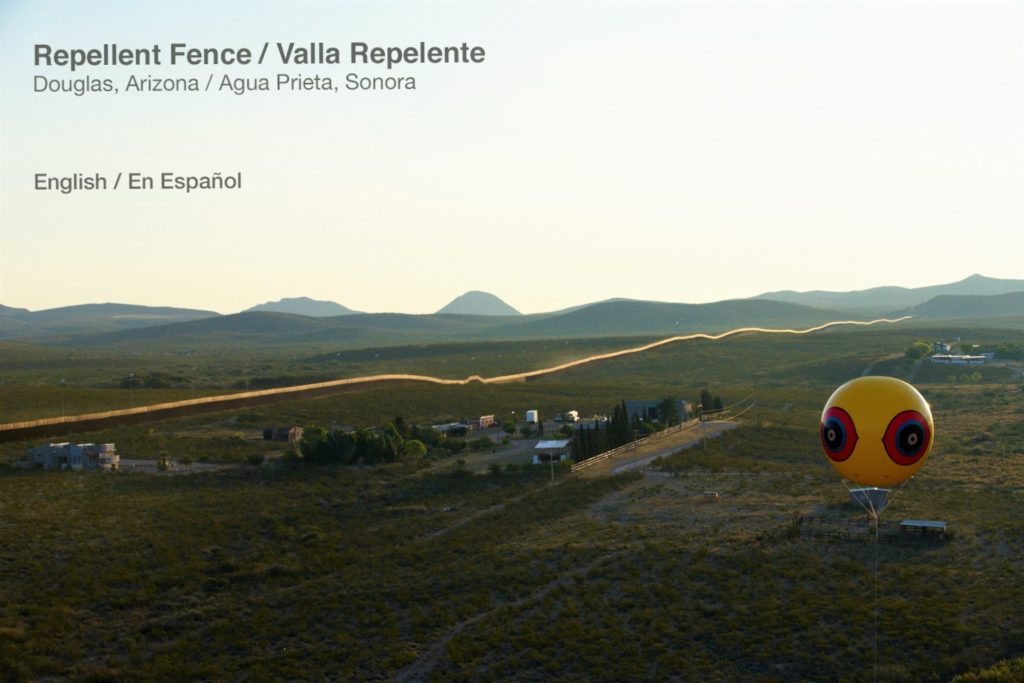

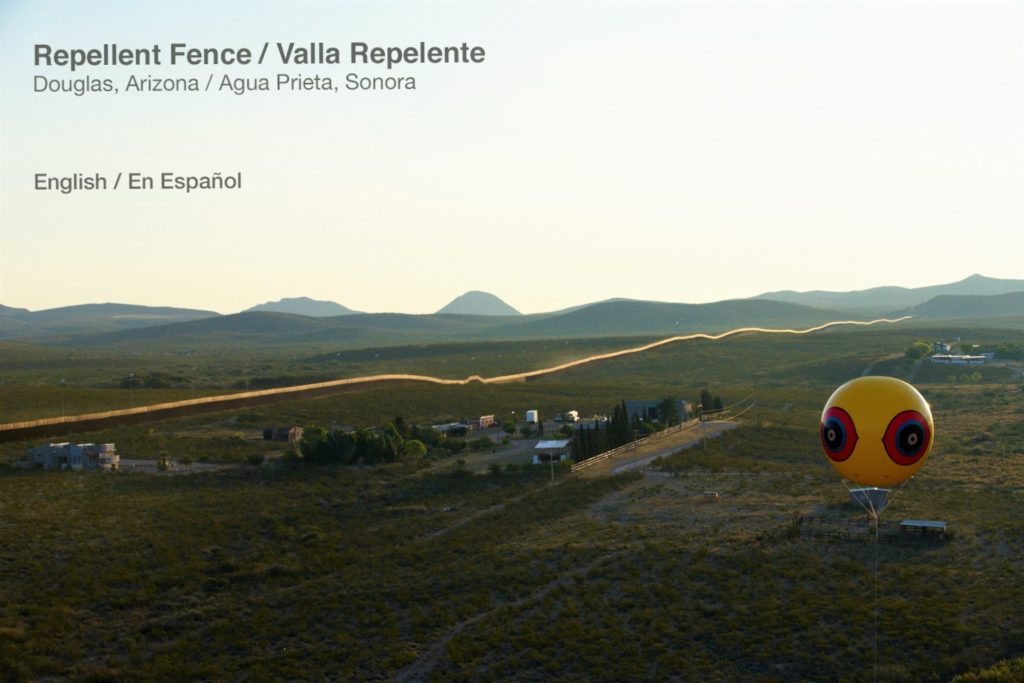

Postcommodity is a collective of Indigenous artists from different backgrounds and mediums, combining to create musical instrument installations, video, sound and sculpture. Their Repellent Fence land art installation floated Scare-Eye bird-repellent balloons over the border between Arizona and Sonora, another example of Geo-Fauvism, art of the wild.

Land Art: “Repellent Fence / Valla Repelente”

By Postcommodity, Published in Art 21 Magazine

Continuing their exploration of contested spaces, Postcommodity recently presented Repellent Fence / Valla Repelente, the largest bi-national land art installation ever exhibited on the US/Mexico border. The temporary, two-mile-long fence was installed in collaboration with the local community from October 9 through 12, 2015, near Douglas, Arizona and Agua Prieta, Sonora. Comprised of twenty-eight tethered Scare-Eye bird-repellent balloons measuring 10 feet in diameter, Repellent Fence floated 100 feet above the desert landscape. During its installation, the work bisected the US/Mexico border and traced an ancient trade route, using a ready-made form of indigenous spiritual mediators to join the communities of Douglas and Agua Prieta.

STORY: Dancing Devils of Venezuela Challenge US Consumer Culture

Watch this video on YouTube

Repellent Fence/Valla Repelente – 2015 — Postcommodity, Music by Luciernaga.

Land art installation and community engagement (Earth, cinder block, para-cord, pvc spheres, helium). US/Mexico Border, Douglas, Arizona / Agua Prieta, Sonora.

In the following interview, Postcommodity responds to five questions about the project posed by Julio Morales, a curator at the Arizona State University Art Museum.

Julio Morales (JM): What were the initial influences that helped shape Repellent Fence?

Postcommodity: One of the most significant influences was the indigenous experience in southern Arizona and northern Sonora. We were thinking about how the US/Mexico border divides indigenous tribes and their lands, and we were interested in learning more about the experiences that result from a border splitting one’s tribe. Our learning framed our perception of the borderlands and provided an important context for working within this landscape. In preparing Repellent Fence for installation, we found that dividing people from themselves (and the land beneath communities) leads to brutality, permanent loss, and significant collateral damage. For this reason—and many others, like social, cultural, economic, and political stratification—the borderlands are a microcosm of the Western Hemisphere, where many human-rights crises are intensified by the mass and density of the population, and laid bare for everyone to see.

Postcommodity contributor Cristobal Martinez’s Radio Healer is composed of indigenous re-imagined ceremonies, music, dance, narrative, images, using a convolution of indigenous electronic tools (such as hacked electronic musical instruments and computers), and traditional ceremonial implements (such as indigenous flutes, rattles, and animal calls) to encourage local generative community dialogues. The purpose of this cultural work is to build local literacies capacities to critically engage increasing technological velocities and their implications for daily life.

Other important influences were our personal experiences growing up in the Southwest, a place dominated by the agricultural industry. Throughout our lives, the San Joaquin Valley in California, and river valleys throughout the southwestern United States, have fed the world by means of cheap, indigenous, migrant labor, which is dangerous, exploitative, and illegal. We will never forget the images of indigenous people standing near the roadside, directing crop dusters, and getting completely showered by a rainbow of pesticides reflecting daylight. We grew up watching Cesar Chavez being demonized on TV for organizing indigenous workers around basic human-rights and labor issues. His voice was the first we remember that sought to unify indigenous peoples from the United States, Mexico, and Central America, as well as those from the Philippines. The work of Chavez was incredibly influential in terms of understanding the scale of the indigenous human-rights crisis in the Western Hemisphere, its interconnectedness, and, more specifically, how this crisis was manifested in our communities. It was eye-opening to look beyond the human-rights crisis of our American Indian and Chicano communities, and to begin seeing the enormous scale of these injustices.

Another influential experience is that a couple of us lived in Phoenix for a good portion of our lives, witnessing the insanity of the Maricopa County sheriff, Joe Arpaio, and the extremely conservative legislature under a Republican super-majority. It was mind-blowing to witness elected officials dedicating so much time and so many resources toward codifying racially and culturally chauvinistic laws and policies that structurally disrupt, destabilize, demonize, and exploit the lives and communities of brown people. They reflect Arizona’s legacy of hatred and violence toward American Indians and Mexican Americans. It was like seeing the wheel of America’s worst history be reinvented — day after day, over and over again. Our concern is that legacies of hatred and violence are now exacerbated by the speed of movement—the acceleration of change in climates, resources, cultures, economies, weapons, communications, and politics.

To us, it would be impossible to be indigenous artists in the Southwest and not attempt to produce work that acknowledges these issues—not in a manner that further polarizes people but rather one that encourages respectful public dialogue driven by the rich and dynamic environment of the borderlands.

Watch this video on YouTube

Postcommodity contributor Kade L. Twist – It’s Easy to Live with Promises if you Believe They are Only Ideas.

JM: What are the cultural climates in the border cities of Douglas and Agua Prieta? Can you describe the scenario of how this project can be an important social model for transformation within border cities?

Postcommodity: The cultural climates of Douglas and Agua Prieta are largely constructive and generative. There is a strong desire to restore relationships to what they were before the war on drugs and 9/11. The communities want dialogue and they want to remove divisive barriers that disrupt interdependent relationships. This is evident by the fact that Repellent Fence was produced within the framework of an existing memorandum of understanding (MOU) between Agua Prieta and Douglas, which seeks to promote bi-national dialogue, collaboration, and regional economic development that is mutually beneficial.

Expecting Repellent Fence to function as a model for transformation is a heavy burden to place upon a work of art. But we think Repellent Fence provides a working example of how socially engaged art can function as a catalyst and facilitative process to enhance dialogue and consensus building. We also believe that Repellent Fence and its creative process demonstrate a model by which a community-determined metaphor can be positioned in ways that advance community self-determination in order to influence social policy, community development, and public memory. This is the generative and transformative role of ceremony. We think that the more Repellent Fence is perceived as a public ceremony, the greater the potential is for us all to realize positive impacts.

STORY: Kuuchamaa: The Exalted High Place of the Kumeyaay

Watch this video on YouTube

Excerpts from Raven Chacon and Robert Henke’s 40 minute moonlight performance at Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, September 20th, 2013. Presented by New Mexico Arts, International Land-Sensitive Art Foundation and Navajo Nation Museum. Shot and cut by D.E. Hyde and Blackhorse Lowe.

JM: Can you describe the concept of suturing and your use of it in the context of this project?

Postcommodity: This was a concept that emerged during our initial round of community meetings in Douglas and Agua Prieta. When people saw our digital rendering of the proposed work, which was an aerial view, the most common response was that it looked like a giant suture, stitching together the land divided by the border and making it whole again. Responding to the visual proposal and to the goals and objectives of the work, they defined and positioned Repellent Fence as a community metaphor. So, from their perspective, the work is something that demonstrates the historical and contemporary interconnectedness of the Western Hemisphere and stitches a divided land together in a restorative manner. This notion quickly became the frame of reference for discussing the project and facilitating the bi-national collaboration needed to implement the work. And it also became the frame of reference for looking toward the future and rationalizing the true power of the MOU between the two cities.

STORY: Missions of Culture: Reclaiming Indigenous Wisdom with Caroline Ward Holland

Watch this video on YouTube

Raven Chacon – Yellowface Song

JM: You state that the Repellent Fence project attempts to “reaffirm the indigeneity of immigrant peoples.” Can you talk about this proposed outcome?

Postcommodity: In addition to functioning as a metaphorical suture, Repellent Fence is also engaged in a process of cultural, political, economic, and semiotic repatriation. What we have learned from the experiences of American Indian tribes is that, in order for a community to exercise meaningful self-determination, it must also repatriate and reactivate its intellectual, cultural, and spiritual property; in other words, it must reactivate its memory. Our memories connect the past with the present, and provide us with a foundation for healing and reconnecting communities in a sustainable manner. Acknowledging the indigeneity of migrants is a vital component of a larger process of reclaiming our places as self-determined indigenous peoples. It disrupts geopolitical violence by reasserting the contemporary relevancy of our shared histories and narratives as interconnected peoples with a historical connection to the Western Hemisphere dating back thousands of years before European colonization.

STORY: Fracking Boom Surrounds Sacred Chaco Canyon

[vimeo clip_id="110402157" width=600 height=338 ]Raven Chacon: Artist Talk at the Aboriginal Gathering Place, Emily Carr University

JM: Repellent Fence goes beyond what we traditionally think of as land art. What new strategies and aesthetic qualities are you bringing to this genre?

Postcommodity: Land artworks tend to seem like unwanted impositions onto the land—a stamp or flag that says, “I was here and conquered.” As beautiful as [Walter De Maria’s work] may be, we don’t believe the locals in the western New Mexican desert asked for a bunch of lightning rods to be permanently placed in the ground there. So from the beginning, we knew that the materials in this work had to be temporary. The desert is greater than all of us, and if Repellent Fence was not fleeting, it would be just as obtrusive as an actual steel fence.

With Repellent Fence, we apply our shared indigenous worldview to our strategies and aesthetics, as we have done throughout our entire body of work. We use concepts of reimagined ceremony to facilitate transformative experiences for the audience and participants that enable the repatriation and re-contextualization of community-based forms of indigenous knowledge. In this regard, we emphasize the temporal and ephemeral aesthetic and conceptual qualities of the work as a means of enhancing public awareness of what it means to exist in the present moment, physically and spiritually, and to personally experience the nonlinear relationships between past, future, and present that better exemplify this recovered knowledge. That’s the transformative quality we try to bring to this work and to the field of land art. It’s not about digging a gash in the earth or constructing some sort of monument. It’s about respectfully facilitating meaningful relationships between people, metaphors, and place that, in concert, support the experiential processes of transformation. In our work, it’s about using the land as a mediator within these processes and having a reverence for complexity and dialogue.

About Postcommodity

The members of Postcommodity come together to function as a learning community. The artists teach and mentor one another across disciplines in order to produce a collective with a dynamic and robust capacity. Together the artists of Postcommodity are able to achieve ideas that exceed their abilities as individuals.

Raven Chacon (Navajo) is a composer of chamber music, a performer of experimental noise music, and an installation artist. He performs regularly as a solo artist as well as with numerous ensembles in the Southwest. Chacon’s work explores overdriven sounds of acoustic handmade instruments through electric systems and the direct and indirect audio feedback that result.

Cristobal Martinez (Xicano) is a digital designer, artist, and scholar in rhetoric, the learning sciences, and diversity studies. His work is grounded in technical, rhetorical, and aesthetic knowledge of the design, composition, performance, and application of media art. Martinez designs immersive environments while testing and refining these interactive experiences among diverse groups of people and across disciplines. He is also a critical-studies scholar in writing, rhetoric, and new literacies. In threading his art practice and scholarship together, Martinez engages public audiences in inquiry, critique, and deliberation on socio-economic inequities, indigenous self-determination, building and reactivating public memory, and digital media and learning.

Kade L. Twist (Cherokee) is a public-affairs consultant specializing in American Indian health care, technology, and community development and an interdisciplinary artist working with video, sound, interactive media, text, and installation environments. His work examines the unresolved tensions between market-driven systems, consumerism, and American Indian cultural self-determination.

Updated 4 May 2021

While the balloons seemed so large when viewed up close, they appeared only as small dots when looking across one side of the border to the other, serving to remind viewers that personal and communal perspectives shift in time and space. The border is an artificial edifice; the migrant hasn’t always been the other.

Pingback: Appropriating the Media Barrage with Negativland | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Speaking in Sonic Tongues - dublab's DJ Nanny Cantaloupe | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: A Change in Dimension – YDP – your daily picture

Pingback: Dancing Devils of Venezuela Challenge US Consumer Culture

Pingback: Geo-Fauvism: Waking to the Wild Earth Through Visual Art - WilderUtopia